Walid awoke before dawn. He dressed, left his studio apartment and walked the 10 minutes to his local mosque for morning prayer. It was a daily routine, a walk he enjoyed. It was a dark and cold March morning in Ronneby, Sweden, with the first gleamings of sunrise still an hour away.

By 6 a.m., Walid al-Zaytun, a 50-year-old owner of a towing business, had returned home and was sleeping peacefully when the police kicked in his door. In the darkness, they dragged him from his bed and pinned him against the wall with such force that they broke one of his teeth. They demanded his computer, the password to his phone, the keys to his car. Another Swedish officer then threw him to the floor and drove his knee into his back so hard Walid would later require surgery. The officer tried to snap a photo of Walid’s face to keep as a private memento of the day.

“It was like a dream,” Walid told The Black Sea. “They were screaming, and the place was in complete darkness. They were in masks and wore black clothes. I couldn’t understand what was happening.”

After being handcuffed and blindfolded, Walid was transported to the station in nearby Karlskrona and charged with committing war crimes in his native Syria nearly a decade earlier.

That same morning - 21 March 2023 – police in Belgium and Germany arrested two more Syrian refugees, Eid Muhameed and Mustafa Marastawi. The transnational police operation was the culmination of a years-long probe into an ISIS-led execution in the Syrian desert town of Al-Sawana back in May 2015.

Senior District Attorney Reena Devgun of the National Unit against International and Organized Crime said at the time, “The indictment concerns very serious crimes committed during the war in Syria. The investigation has been extensive and complicated, and interrogations have been carried out in several different countries.”

No crime had been committed in Europe. The men were charged under a legal principle known as ‘universal jurisdiction,’ which gives countries authority to charge war crimes committed anywhere in the world. Devgun sought a 24-year sentence for Walid and his deportation.

Prosecutions of Syrian war criminals are on the rise in Europe. What makes Walid’s case remarkable is that it was not the police that built it. It was a team of civilian investigators working for a European non-profit organisation called the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) that has made a name for itself as a respected advocate of Syrian human rights.

In 2020, the organisation began collecting evidence under the supervision of one man. A glowing New Yorker profile published in September last year lauded the work of Mustafa ‘Homs’, a Syrian lawyer and CIJA’s deputy chief of Syria investigations who died in the February earthquake in Hatay, Turkey, last year, a month before Walid’s arrest in March.

Mustafa had “identified and collected witness statements against a trio of Syrian ISIS members who had been active in a remote village in the deserts of central Syria and were now scattered across Western Europe,” the New Yorker said. “All three men were arrested after his death.”

Following a month-long trial, the Swedish court acquitted Walid al-Zaytun of all charges in early May. In their ruling, the judges said the prosecution failed to prove its case. They also raised serious concerns that CIJA’s witnesses had changed their statements “in several important respects” throughout the investigation and “may have deliberately provided incorrect information.”

The judge ruled that CIJA’s dossier, upon which the entire case was constructed, was essentially worthless: it could “only be assigned an extremely limited probative value” and should be “excluded as the basis for a conviction”.

The Black Sea examined thousands of pages of evidence and talked to witnesses, including Walid himself. That CIJA’s evidence even reached a courtroom points to a deficiency at the heart of Syrian war crimes prosecutions. It is based on a handful of testimonies with significant and glaring inconsistencies from the outset. More troubling, however, are accusations that CIJA - an organisation with millions in government funding - and its investigators tampered with witness statements and offered enticements of European visas.

The investigation, arrests, and prosecution of Walid al-Zaytun, Eid Muhameed, and Mustafa Marastawi also shed light on a largely opaque world operating just beyond the confines of traditional legal procedures: the burgeoning multimillion-euro industry of non-profit war crimes investigations.

CIJA is among several European NGOs acting alongside the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM), a “justice facilitator” mandated by the United Nations in 2016 to catalogue and preserve evidence of war crimes in Syria and support judicial proceedings globally. While universal jurisdiction can offer a valuable legal pathway for victims to obtain justice, it increasingly relies on outsourcing the work traditionally done by police and prosecutors to third-party private organisations like CIJA, which operate without the same level of scrutiny and accountability.

Walid, who spent more than a year in pre-trial detention in Sweden, claims the case against him stems from one man’s vendetta: a former colleague from Al-Sawana named Ayoub Mohammed al-Shafi al-Asaad, accused by many of being a loyalist of the Assad regime. His motivation, according to Walid, is a long-standing grudge over a relative’s spurned marriage proposal.

After reviewing the case, respected Syrian human rights lawyer Anwar al-Bunni, himself a witness in a Syrian war crimes trial, told The Black Sea, “If I had been asked from the beginning, I would have said that this case could never result in a conviction.”

THE CASE ACCORDING TO CIJA

Dissecting the chaotic narrative of CIJA’s witnesses is a challenge. However, the overall account gleaned from the documents in the case is as follows:

Before Sweden, before the war, Walid al-Zaytun worked for many years as a bookkeeper and then head of fuel services at a phosphate mine in the small desert town of Al-Sawana, close to the ancient city of Palmyra. The mine was and is the area’s principal employer. Two of the three defendants worked there, as did many witnesses. A lot of the townsfolk are related in some way.

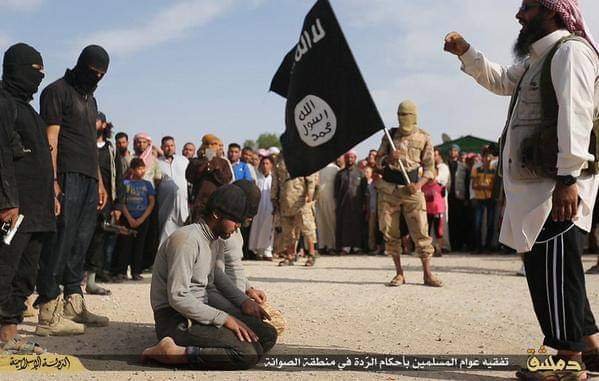

On the evening of 20 May 2015, ISIS captured Al-Sawana without firing a shot. In the aftermath, they imposed a harsh regime on locals, punishing them for minor infractions with floggings and erecting a large screen upon which they broadcast videos of executions.

ISIS’s focus in these first days was rounding up and confiscating the weapons of Baath Brigade members, a pro-Assad volunteer militia established in 2012 to help control dissent during the civilian uprising. One brigade member and mine employee fled Al-Sawana with his rifle but was later detained at a makeshift prison and interrogation centre. According to CIJA’s report, it was here that Walid tormented him and made threats to his life.

Walid, it is alleged, along with other Al-Sawana men, including the two defendants, were part of an ISIS sleeper cell that activated once the jihadist group took the town. Armed with an AK and patrolling the city, Walid escorted ISIS to the houses of brigade members and regime loyalists.

A week or so after the incursion, ISIS ordered the residents to gather at Suweis Square, a residential area close to the town’s mosque. There was something they had to see. The crowd looked on as Walid Al-Zaytun, Mustafa Marastawi, and Eid Muhameed, along with two other men, Daham al-Battman and Basel Marastawi, brought two captured members of the rival anti-Assad Islamist group, Jaysh al-Islam.

Bound and blindfolded, the fighters were presented before a Saudi man named Abu Rami Al Shari, who charged them as “apostates” and demanded they join ISIS or face execution. When the prisoners refused, Al Shari raised his hand. One of two hooded men standing guard shot them both in the head.

There is no suggestion that the three defendants murdered the two men themselves. But CIJA documented how Walid and the others delivered them to their deaths in Suweis Square. Sometime after, he and Daham al-Battman, a slight high schooler around 18 years old, tied one of the corpses to the back of Walid’s truck and dragged him around town, honking to draw the attention of passersby. At a roundabout 100 metres from the execution site, they tied the man to a lamppost, and Daham al-Battman threw a chisel at his head, dislodging his eye. This is one of the multiple versions of what happened to the victim’s eye and who carried out the attack, illustrating the contradictions in testimony.

They left the corpse there as a warning to the town.

Within weeks, the Syrian regime bombed Al-Sawana. In the chaos, Walid and the other defendants fled to Turkey, along with much of Al-Sawana’s population. The trio smuggled themselves into Germany, Belgium, and Sweden, leaving behind only the memory of the terrible war crimes for which they would never be accountable – until a CIJA investigator learned about the story.

THE RISE OF THE CIVILIAN PROSECUTORS

CIJA was founded in 2012 by former Canadian soldier William Harry Wiley. After working for the International Criminal Court tribunals investigating crimes in Yugoslavia and Rwanda and a stint on Saddam Hussein’s legal team, Wiley started a security consultancy before becoming what he describes as a “practitioner” of international criminal and humanitarian law. When the Syrian war broke out, Wiley saw an opportunity.

In the shadow of the Syrian conflict, millions escaped the country into Turkey. Among the refugees were regime agents, military officials, and regular soldiers, who quickly established the “defected officers’ camp” in Antakya, the Hatay region, near the Syrian border.

Wiley was already training Syrians, many found in the Antakya camp, in evidence collection for the British government. This was when he met Mustafa Saad al-Din, better known as the late Mustafa ‘Homs’, who would join the Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability, as CIJA was then known, in 2012 and be assigned the codename 0001.

CIJA and Mustafa grew a network of defectors, activists, and anti-Assad Islamist groups, “partners” who they tasked with smuggling vital documents from ransacked Syrian intelligence branches. Early efforts were haphazard at best and contributed to the likely deaths of two, possibly three, Syrians before, as Wiley told the New Yorker, he decided there “needs to be a plan.. as opposed to just throwing the shit in the car and going, ‘Well, God decides.’”

Over the next few years, CIJA amassed an extensive repository of over a million documents and personal testimonies, evidence of disappearances, torture, rapes, and murder by the Assad regime and its enforcers. Currently housed at a facility in Lisbon, Portugal, CIJA’s cache is made available upon request to police and prosecutors worldwide.

The model proved enormously effective. Despite no formal legal qualifications, Wiley oversees an influential organisation with a €30 million budget over the past five years, funded by the US State Department and the governments of Sweden, France, Netherlands and the UK, among others. Its two boards and senior management positions are made up not of Syrians but former US prosecutors and lawyers, many of whom worked for State Department-funded legal programs in Iraq and Afghanistan and special war crimes tribunals. One name stands out, however: Saudi businessman Nawaf Obaid, a former special advisor to both the Saudi regime and to the country’s ambassador to the UK, is a board member.

Two sources told us that CIJA’s custodianship of the Syrian regime’s worst crimes is not altogether altruistic; a Middle Eastern NGO head in France claimed that CIJA offered to sell them the data for €1 million.

Other cracks have appeared in CIJA's image. In 2020, the OLAF, the European anti-fraud office, announced that CIJA and partners (among them an offshore company Wiley controlled) had defrauded the EU budget of €2 million by committing “massive” and “widespread violations.” This included the “submission of false documents, irregular invoicing, and profiteering” as part of a justice initiative to “support possible prosecutions for violations of International Criminal and Humanitarian Law in Syria.”

Independent war crimes teams like CIJA often work in cooperation with the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism - often known as the “mechanism” – a UN project established in 2016 to “assist in the investigation and prosecution of persons responsible” for Syrian atrocities.

On 3 April 2018, IIIM signed a “protocol of cooperation” with 28 Syrian-led civil society organisations. It set out a “general framework,” but few practicalities are public, including the names of the organisations. There appears to be no formal qualification for admitting members, and the vetting process is unclear.

CIJA was among those selected. When The Black Sea inquired about how IIIM chooses its cooperators, it told us that it knows all the main players. All CSO partners nevertheless perform their work independently, it said. But CIJA has leveraged this position, falsely informing witnesses of its “mandate to collect and preserve evidence to support future prosecutions of alleged perpetrators of international crimes before local, foreign, or international courts.” IIIM told The Black Sea that no such mandate exists for CSOs.

CIJA has generated a great deal of positive press in the West, garnering a reputation as a linchpin of war crimes investigations against Syrians hiding in Europe, but increasingly other state crimes in Ukraine and Myanmar. There is little evidence, however, supporting Mustafa's title as “the most prolific war-crimes investigator in history.”

Much of its work involves expert witness testimony and supplying suspect dossiers from its archive to police and prosecutors. Its investigation into the Al-Sawana killings appears to be the first time it carried out a proactive investigation that led to arrests. In its annual report, it accuses the men of “pillage, torture, executions, and the mutilation of corpses.”

“NOBODY TOLD THE STORY LIKE THE OTHERS.”

When the trial commenced in March this year, Walid faced two counts of war crimes and decades in prison. No one disputes that the execution of the two FSA fighters happened. Years of investigation, however, failed to unearth any documentary evidence that proved Walid’s guilt; there were no photos or videos of him or the others dressed in ISIS garb or carrying weapons, even though images of the execution surfaced online. Nor is there any suggestion Walid had ever subscribed to ISIS’s Salafi jihadist ideology.

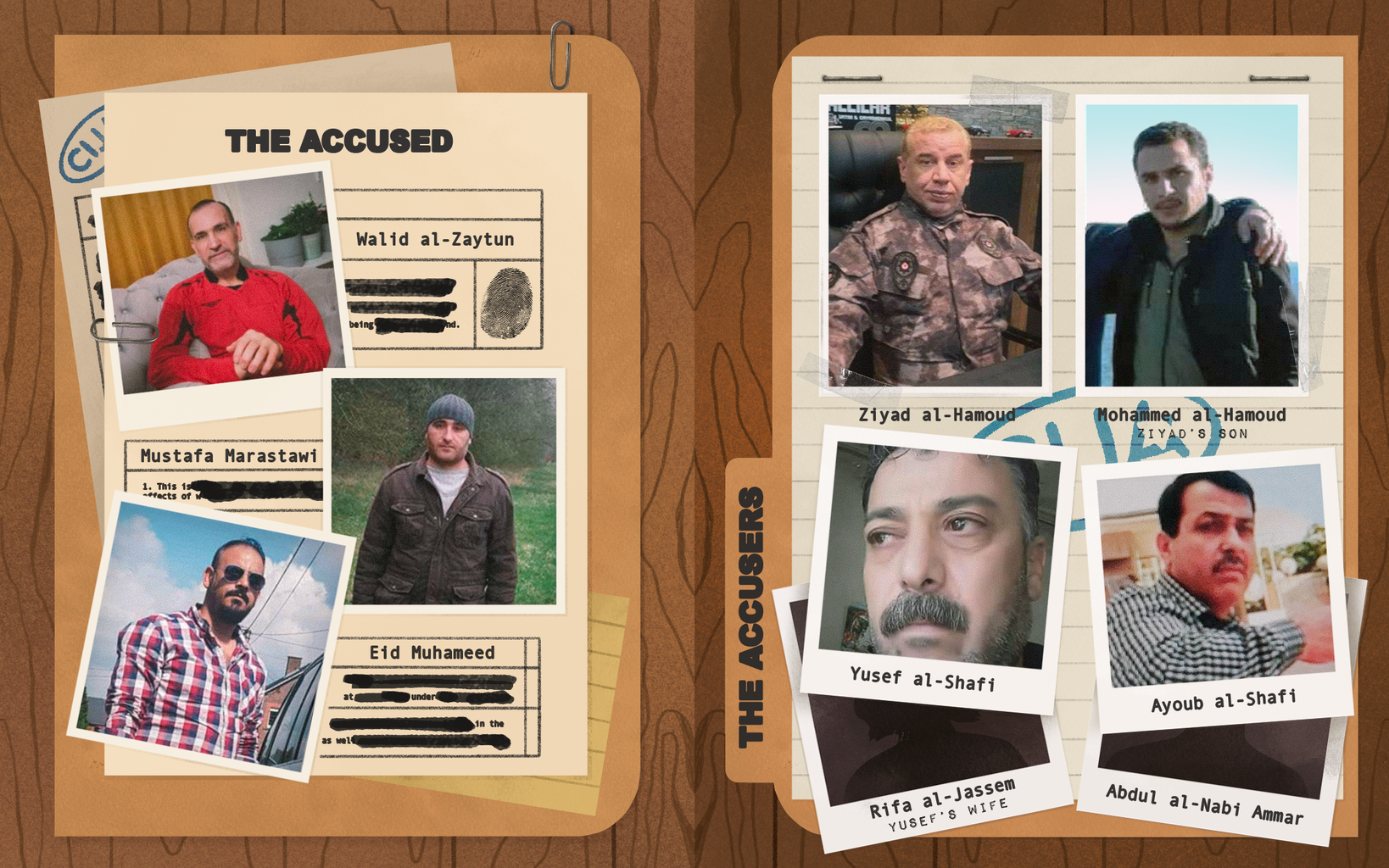

The prosecution would rely instead on testimonies gathered three years before by CIJA. And it started with five witnesses. These five, the Swedish judges later said, were central to the CIJA dossier and the case.

“All those witnesses were inside one circle,” Walid explained. “But nobody told the story like the others.” We found vast, undeniable contradictions and inconsistencies when we examined the evidence against Walid.

CIJA’s Mustafa Homs met Ayoub al-Shafi in the early summer of 2020 at the Antakya refugee camp, where Ayoub told him the story of an execution in his hometown of Al-Sawana. The guilty men were in Europe; he told Mustafa that he had been tracking them for years. He was enraged to find them “living their lives of luxury.” For Europe’s own protection, they needed to be brought to justice.

Mustafa never interviewed Ayoub as a formal witness. Between July and September 2020, Mustafa went on to interview five witnesses on the record: Ayoub’s older brother, Yusef al-Shafi and sister-in-law, Rifa al-Jaseem; Ziyad al-Hamoud, a former Ba’ath Brigade security guard and his son, Mohammed al-Hamoud; and Abdul al-Nabi Ammar, a shift head at the Al-Sawana mine.

From these five testimonies, Mustafa reconstructed the Suweis Square execution. What arose from his inquiries certainly presented questions about the actions of Walid and the other suspects during ISIS’s reign over the region. But Mustafa’s narrative was lacking in concrete, corroborated evidence of the two war crimes that Walid would be later charged with. Everyone said something different.

None of the witnesses attested that Walid delivered the FSA fighters to the square that day. With regards to the posthumous mutilation of the corpses around town, Yusef, Ziyad, and Mohammed claim to have seen it, and they gave conflicting accounts of who had dragged the dead man to the roundabout. Al-Nabi Ammar said that he did not witness the mutilation but simply heard about it from Ayoub, who he said implicated Mustafa Marastawi rather than Walid. Only Mohammed and Ziyad accused Daham al-Battman of shooting the corpse before the mutilation, an accusation that later disappeared.

Ziyad had told Mustafa that he “saw with his own eyes” both Walid al-Zaytun and Daham al-Battman dragging a man tied to their car – “honking the car to draw attention” – to the roundabout where “they shot him and hit him in the eye with a chisel.”

According to almost everyone, Ziyad was not present. Even his son Mohammed said his father was not there that day. “Daham al-Battman and Walid al-Zaytun got out of the Hyundai car and untied the soldier,” Ziyad’s son Mohammed said. “Then Daham al-Battman shot him in the head with his gun, then they dragged the body and tied it to a pole in the middle of the roundabout.” Mustafa’s note from the statement admits that Ziyad “mixed up what he saw himself with what he heard from his son Mohammed or from others.”

“I was there during the execution of two people from the Syrian Free Army,” said Walid. “I saw that crime with my own eyes, so I told them during the investigation that it is impossible that their witness was there because he told them things that didn’t happen there. I was there, and I saw everything.”

Any discrepancies might have been resolved by listening back to the interviews. But Mustafa had not recorded any of them, taking only summaries of their statements in Arabic. Collectively, the narrative made little sense of who had committed what war crime, if any.

CIJA seemingly ignored these inconsistencies. In late September, only a few weeks after Mustafa spoke to Mohammed al-Hamoud, the organisation delivered their dossier to the authorities in Europe. The Swedish court – and the prosecutors – later adjudged CIJA’s work as worthless for a criminal indictment. But it was enough to launch a formal investigation. Walid was put under surveillance.

UNIVERSAL JURISDICTION: EUROPEAN JUSTICE “BEYOND ITS BORDERS”

War crimes prosecutions are a tricky business. Most involve specialist tribunals and the International Criminal Court. Many countries, like Syria, the United States, and Turkey, have never signed the Rome Statute that grants the ICC jurisdiction. In the last two decades, Europe has turned to national universal jurisdiction laws.

These laws permit countries to hold accountable any citizens - or residents - who committed the most serious of crimes “beyond its borders” – genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Sweden’s Universal Crime Act is among the most liberal interpretations of universal jurisdiction.

European countries have initiated more than 250 universal jurisdiction cases in the past 20 years, with Germany, France, and Spain topping the list (Sweden is fifth). More than 36% of these have been for crimes committed in Syria, and a quarter are against Syrian nationals, leading to accusations that racism plays a significant role in its application.

Cases range from in absentia trials of President of Syria Bashar al-Assad and his cronies to returning ISIS fighters who posted pictures of themselves on social media humiliating the deceased. Very few are for the most serious crimes of mass slaughter or prolonged human rights abuses. One was Anwar Raslan, a state intelligence officer convicted in Koblenz, Germany, in 2022 for his role in the torture, abuse, or murder of thousands of dissidents.

In many ways, his arrest and 25-year sentence was a rainmaker. It represented a crucial victory for international justice and a beacon of hope for displaced Syrians that the elusive accountability they crave might one day be possible. It also brought to the world’s attention the role of civil organisations, many of them Syrian-led, who were quick to claim credit for the success, leading to a certain degree of myth-making (CIJA and other civil organisations played no role in the apprehension of Anwar Raslan, who contacted authorities himself for a different matter).

“Unfortunately, after the Koblenz trial, there is now competition among European countries to prosecute war criminals from Syria. From one perspective, this is very good for justice in Syria,” said Anwar al-Bunni, a witness in the Raslan case who was once tortured on the General’s orders. From another, he said, there can be “significant issues” like those seen in Walid’s case.

European prosecutors generally lack the tools and experience to conduct the kind of thorough work required to prove complex war crimes abroad. Long-time dictator al-Assad still runs Syria, for example, rendering the possibility of state cooperation for boots-on-the-ground investigations a pointless fantasy.

“The big problem is that European countries were not present when these crimes took place in Syria,” al-Bunni told us. Civil groups like CIJA now play a key function in these accountability efforts. But it is one which, as the Swedish court stated, “is not subject to the same regulations as… European police authorities.”

“CIJA is an organisation that doesn’t have Syrians working in it, so they cannot accurately assess what is happening in Syria. Perhaps they work with some Syrians to collect testimonies, but not to evaluate them.”

A DIFFERENT STORY IN TURKEY

The Swedes had a problem. None of the CIJA evidence “could be used in the prosecution in Sweden.” They said as much when eight months after receiving the CIJA files, they contacted the Turkish authorities to request assistance in conducting more formal interviews.

If the prosecutors believed that more official surroundings would clarify the vast discrepancies in the witnesses’ stories, they were mistaken. The narrative was about to become ever more unreliable. And extreme.

In April 2022, in the prosecutor’s office of the southern Turkish city of Mersin, father and son Ziyad and Mohammed al-Hamoud recounted a version of events so outlandish that it should have raised serious doubts about the case.

Much had changed in their statements since the two first talked to Mustafa and CIJA two years earlier. For one thing, Ziyad and Mohammed no longer contradicted each other; sections of the testimonies were identical (this is likely to be in part caused by the sloppy work of the prosecution office in Mersin).

That wasn’t the only thing that changed. They detailed how Walid had been “active in Daesh (ISIS) before 2015” and that his crew were routinely “capturing people who opposed them, executing them in the middle of the street, sometimes killing them with a long-barreled weapon, and sometimes beheading people with a long machete-style knife.”

Regarding Suweis Square events, they painted a much more gruesome picture of Walid and his actions than in their previous statements to CIJA. “Walid also started torturing them in the square to make an example and removing the person's eye with an iron rod,” they said. Walid also cut off “a soldier's head with a machete.” (Ziyad later denied at trial that he said these things).

Abdul al-Nabi Ammar, the first person Mustafa questioned on record, was interviewed twice by Turkish prosecutors in Istanbul in January and October 2022. His initial statement essentially echoed what he told CIJA previously: that there had been an execution, and Walid and the other men were present. His second statement, carried out with the Swedes present via video feed, shows a dramatic shift, now running more closely to Ziyad and Mohammed’s version of events that were more damning to Walid.

Rather than just hearing the story from Ayoub, as he had stated to Mustafa in 2020, Abdul al-Nabi Ammar now suddenly “remembered” that he saw for himself Walid dragging a person behind his pickup truck to the roundabout, where Daham al-Battman “tied him to a metal [lamppost]” and then “gouged out one of his eyes with a cutting tool.”

At the end of the interview, Swedish prosecutors declined to ask Abdul al-Nabi Ammar any follow-up questions.

Even though their own inquiries had produced more questions than answers, they had seemingly heard enough from CIJA’s original five witnesses. By then, in the autumn of 2022, preparations were already underway to bring Ziyad and Mohammed al-Hamoud to Sweden. The pair were absolutely central to the prosecution’s case, according to judges, who wrote that the evidence presented in court against Walid “consists essentially of the statements of the witnesses Mohammed al-Hamoud and Ziyad al-Hamoud.”

The Black Sea wrote to Reena Devgun with questions. She told us she is “reluctant to talk about this case until the trial in Germany is final.”

ENTER THE UN/VISAS TO EUROPE

The CIJA investigation didn’t only lead to the prosecution of Walid. Within days of Walid’s trial beginning in Sweden, Mustafa Marastawi’s started in April this year in Germany, where he has refugee status (the trial of Eid Muhameed is set for spring next year). In many ways, the case against him, which is still ongoing, is as weak as Walid’s. But it includes charges that he was also a member of a terrorist organisation, ISIS, crimes often excluded from universal jurisdiction laws because it is not listed in the Rome Statute. Germany allows it.

The German indictment names Abdul al-Nabi Ammar, Ziyad and Mohammed al-Hamoud, as well as two other codenamed witnesses, as the basis for the arrest warrant and the initiation of proceedings. The unnamed witnesses are Yusef and his wife Rifa (The Black Sea has chosen to name the witnesses because their identities are included in the judgment or publicly disclosed by Walid and others).

German authorities approached IIIM, the UN project tasked with examining atrocities in Syria. IIIM conducted a substantive two-day interrogation of Yusef, who they did not name, on 17 and 18 August 2022 in Turkey. They shared the interview with the Swedish prosecution.

Yusef had been withholding vital information, he said, blaming concern over the motives of the investigators and the fear that “his neighbours, people might know” he was talking to authorities. He now had much more to say. His new statement took place over two days. It runs 200 pages long and contains extraordinary new accusations.

Yusef now alleged that Walid and the other men drove the two FSA fighters to Suwais Square to be killed. Whereas before, he made no mention of the mutilation, he now “believe[s] it was Eid” who put a knife into the eye of the corpse.

Among his claims are that Walid and Mustafa Marastawi commanded a group of teenagers to unload and bury several suspicious containers. “They told the boys to be extremely careful,” he said. When Yusef asked the boys about the barrels, he told IIIM that they described the contents as smelling like “rotten eggs,” insinuating they were burying chemical weapons.

Yusef also recounted an overnight visit to nearby Palmyra, a famous tourist spot in the desert, a few weeks after ISIS took control of the area. His tale is a cacophony of ultraviolence and brutality as ISIS punished the locals: a gay man and a judge being thrown from buildings, and the execution of famous archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad, murdered after refusing to disclose the location of hidden Palmyra artefacts. He saw the body strung up in the lamppost.

Other events include the murder and beheading of 19-year-old Suleiman al-Jassem, his wife’s nephew, after being informed on by Eid Muhameed. A military sergeant was beheaded, as were two thieves. A person’s fingers were cut off because he was a smoker.

Yusef went on to describe a gruesome ISIS mass execution, where “20 individuals were beheaded” in Palmyra’s famous Roman amphitheatre. Following the murders, he saw Walid al-Zaytun, Mustafa Marastawi, Eid Muhameed, and Daham al-Battman joyfully lead chants of “Allahu Akbar.”

While many events occurred during ISIS's rule in Palmyra, they unfolded over several months rather than one night and in ways that differ significantly from Yusef's account, or they simply didn’t happen. IIIM told us that part of its work involves conducting interviews at the authorities' request. In these instances, they do not assess the evidence. They also said they had no direct dealings with CIJA in the case.

Why might Yusef have embellished his knowledge of events or changed his story to make it more dramatic? Despite CIJA’s public insistence that their investigations were confidential, Yusef appeared aware of significant details of the case. He told IIIM investigators about witnesses who gave testimonies to Turkish police months before. He was also aware that the two witnesses were due to travel to Sweden to give evidence. He even knew the date: 8th January 2023.

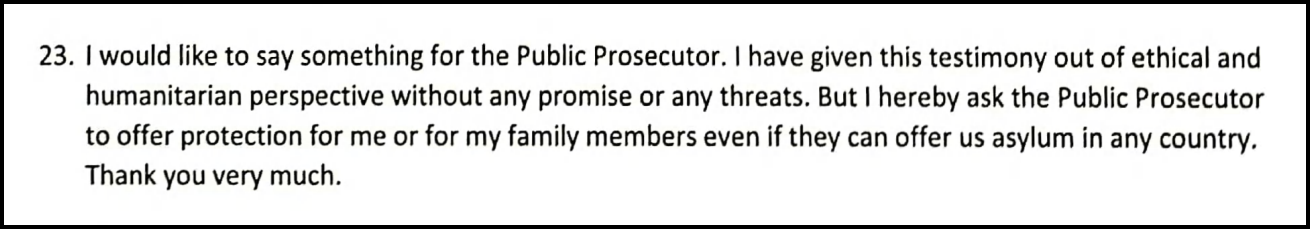

At the end of the interview, Yusef asks IIIM interrogators to make a request on his behalf. “I hereby ask the Public Prosecutor to offer protection for me or for my family members even if they can offer us asylum in any country. Thank you very much.”

His remarks belie what might be the real motivation for why a small group of witnesses might promote a false story about war crimes in Syria. Others told The Black Sea that CIJA’s investigators had enticed their testimonies with offers of visas to Europe.

INVESTIGATING THE INVESTIGATORS

Mohammed al-Ayed is a Syrian media activist from Al-Sawana who lives in Sweden. For the past year, he has been attempting to raise awareness about Walid’s case and draw attention to what he believes are CIJA’s improper tactics and a conspiracy among the witnesses.

Al-Ayed’s interest is a personal one. Walid was married to his sister for many years, and Ayoub and Yusef are his cousins on his mother’s side. When Swedish police interviewed Al-Ayed following Walid’s arrest, he pleaded Walid’s innocence. His statement, he felt, had little impact.

Months after Walid’s arrest, a person working for CIJA emailed Al-Ayed to request assistance with their investigation into the executions, unaware of his connection to Walid. Al-Ayed responded positively, believing he could learn more about the case. When he started providing exculpatory evidence, CIJA discovered his identity and ceased communication. Despite the organisation having initiated contact, they reported him to the Swedish police for disclosing “potentially sensitive information regarding the Sawana investigation.”

Mohammed Al-Ayed described to us how he “conducted a full investigation” and joined the efforts of Mustafa Marastawi’s brother, Basel, who lives in Turkey. Basel described to us how he spoke with “everyone who knows the three accused individuals and who were present” during the ISIS reign over Al-Sawana. “I told them that if they wanted to speak the truth, they should give their testimonies. I gathered these testimonies not to exonerate my brother, but to uncover the truth, as we were greatly harmed by ISIS.” He said he “also wanted people to know about Ayoub, who has entrapped us in this ordeal.”

Basel is among the five men named by CIJA as joining ISIS in Al-Sawana. He denies the allegations, telling us that he was “imprisoned by ISIS under the accusation of collaborating with the Syrian regime and drinking alcohol.” He is also listed on an ISIS “kill list” document provided to Swedish prosecutors. “How could we be involved with [ISIS]?” he asked.

In 2023, Basel was interviewed by a man named Mohammed Omer Abu Abdullah, who claimed to work for the German authorities. He didn’t mention it to Basel, but Abu Abdullah was a legally trained associate of CIJA, although, like Mustafa ‘Homs,’ he never carried out formal legal work for the organization.

Phone recordings and text messages between the two reveal Abu Abdullah recommending that Basel “should say that you gave your testimony before knowing that your brother was a suspect” to avoid raising suspicion that he is simply trying to “exonerate” him. He also asks him to lie about knowing the other witnesses “so they don’t say you [all] agreed on the statements.”

Basel suspected that CIJA’s interactions with other people in the case were equally dubious as his own. Over the next months, he and Mohammed Al-Ayed obtained video rebuttals from over a dozen witnesses and gave them to the defence attorneys. The Black Sea reviewed these videos.

None of them saw Walid and the others joining ISIS or committing crimes. They do describe alarming interactions with the two CIJA lawyers during their efforts to obtain evidence. All made accusations against Ziyad al-Hamoud and brothers Ayoub and Yusef al-Shafi, calling them known informers for the security state. Others said it was Ziyad and Yusef who cooperated with ISIS.

In addition to Mohammed al-Ayed and Basel Marastawi, The Black Sea spoke with three witnesses ahead of Walid’s acquittal in May. Ali Al-Hariri, from Al-Sawana, is a refugee in Turkey. He confirmed to us what he told Mohammed: Walid was innocent of the crimes and had told Abu Abdullah as much when they met in Gaziantep, Turkey, in 2023.

He had given his testimony at the home of Abu Abdullah. But the lawyer later asked him to say that “the meeting was in the evening… at a café,” according to texts and voice messages. When al-Hariri objected, Abu Abdullah replied: “For formalities, we say we met at the café.” al-Hariri also said the lawyer offered to help get Hariri’s brother out of jail in Turkey, that “he had connections” to do so.

Each person we spoke with was surprised that Ayoub al-Shafi and Ziyad al-Hamoud knew about their involvement in the case. CIJA prides itself on discretion, asserting that it keeps the names of witnesses confidential. During Walid’s trial, a CIJA’s head of investigations and operations was reluctant to talk about the real identities of codenamed investigators and witnesses.

Mohammed al-Suleiman, an Al-Sawana native and former phosphate mine employee now living in Turkey, told us that when CIJA’s lawyer Mustafa Saad al-Din approached him to testify, he had Ziyad al-Hamoud with him. Though al-Sulaiman had little to offer about Al-Sawana crimes, he said he felt uneasy that the chief investigator would stay at the home of a key witness and then travel together to what was supposed to be a confidential interview.

Other documents raise questions about how CIJA conducts its interviews -many of which occur via WhatsApp. On at least two occasions, CIJA spoke with witnesses who described the events of Al-Sawana with little or no references to the accused. Subsequent additions, however, suddenly produced new and highly detailed portrayals of the defendant’s crimes.

The Black Sea spoke with a senior member of Jaysh al-Islam, the armed organisation to which the two men executed at Suweis Square belonged. He asked for anonymity on account of his role in an armed group. He said that Walid and the other defendants bore no responsibility for the deaths of the fighters.

He also told us that Abu Abdullah gathered several dozen Syrians in Gaziantep, a city in southern Turkey where hundreds of thousands of refugees have settled. At this event, he said Abu Abdullah announced that he was working with German prosecutors and anyone who could provide evidence in the trial could go to Europe.

We also talked with Ahmed al-Kubba, an electrical engineer from Palmyra who moved to Al-Sawana in 2004 to take a job at the Eastern Phosphate mine. He lived there until shortly after ISIS took the town. Al-Kubba is direct and clear, with no drama or contradictions. He was metres away during the killings. Walid and the others were “absolutely innocent,” he said. None of them joined ISIS. “Look, Walid was a civilian like me and the others. He was really polite and a good person. He was always known for that. I told the same thing in the investigation.”

Al-Kubba first met CIJA’s Mohammed Omer Abu Abdullah during Ramadan last year, at the time of Walid’s arrest. The lawyer wanted to know if al-Kubba knew any of the accused. “I said yes. Because of my job in electricity repair, I know everybody in Al-Sawana… It is a small region.”

The pair met around ten times, always at each others’ homes in Gaziantep. He also sent several audio statements to the lawyer through WhatsApp. “I explained everything in those recordings,” he said. “[Abu Abdullah] told me to send them and that he would take a summary. What I am sure of is that I told him the truth. And I assured him that those persons were absolutely innocent. Walid, Mustafa and Eid were oppressed. I said that they didn’t pledge allegiance to ISIS. They didn’t kill or harm anyone.”

At Abu Abdullah’s request, al-Kubba prepared his documents and sent a copy of his ID. But then the lawyer began trying to coach al-Kubba on “what to say” when anyone called him to confirm his story.

“He said [investigators] would call me and ask me some questions about that issue, then arrange everything to take me to Europe,” he said. After listening for a while, al-Kubba felt uneasy, especially when Abu Abdullah also asked him to declare they’d met in Mersin, 300 km away.

His concern was that his statement – which Abu Abdullah never provided a copy – of the three men’s innocence would not reach the prosecutors, and decided to speak to Mohammed. “How could you trust somebody who tells you to say that you met each other in Mersin?” he said.

Among the accusations levelled against Walid is that he cooperated or represented ISIS in Al-Sawana, acting as a liaison between the group and officials to keep the mine functioning. It was a troubling point raised by the judge. Walid admitted to us that he tried to mediate after a senior director of the company informed him of negotiations. At first, Walid had refused but relented when his boss said the workers would not be paid otherwise. The relationship did not last long, he said, because talks broke down. Then the bombs came, and he fled Al-Sawana. “If I had stayed, I would have been killed [by ISIS],” he said.

Amid the violence they wreaked, the group wanted to keep the town operational. Al-Kubba, like Walid and many others, he said, were forced to carry out services. As an electrician, his skills were important. “Everybody knew that if you refused ISIS’s request, they would kill you or your kid in front of your eyes without any hesitation. They used the same manner with Walid al-Zaytun because Walid was the man responsible for the gas station, so he knew all the details about the job. Exactly like me.”

Interacting with ISIS was not something residents could avoid. But some were more willing. “I got paid just for every fixed job I did. But Yusef and Ziyad worked with ISIS for a monthly salary.”

Ziyad, Yusef, and Ayoub were known as “reporters for security authorities,” he added. As a small region “where everybody knows each other, we can learn about each other easily, so everybody knows that Yusef and his brother Ayoub were employed with the support of security authorities.” In his very first interview with Mustafa, al-Hamoud admitted his membership in the Baath Brigade, a militia armed and supported by the Assad regime.

When asked why these individuals might lie about war crimes, al-Kubba said that CIJA told people, including him, "You would go to Europe.”

He said that he also learned that Ziyad al-Hamoud was acquainted with a CIJA lawyer, as they were both from Homs. And that that lawyer had died in the earthquake in Turkey. “I wonder how he would face his god after he accused innocent people,” al-Kubba said.

Ziyad and his son Mohammed arrived in Sweden on 8th January 2023, months before Walid’s arrest. At the airport in Turkey, they disposed of their IDs and signed a document declaring they would not return.

According to a memo by the prosecution office about the circumstances of their trip to Sweden, the pair’s return was complicated by tensions between Turkey and Sweden caused by the hanging of an effigy of President Erdoğan and then a public burning of the Quran by a far-right politician. Both men, however, had applied for asylum upon their arrival in Sweden before diplomatic ties began to fray.

In a recorded phone call to another witness, Ziyad boasted of how he managed to obtain a visa. "We have a big connection. A very big one,” he said. “The connection is an important person in Turkey who spoke with the consul, and they gave us the visa. This has never happened before in all of Europe and the history of Turkey. They are surprised at how we managed to leave. We got a visa from the consulate."

He went on to say, "Things have started to go well for us, thank God. When I open the company, I will bring you over here, I promise you. God willing.” The Black Sea contacted Ziyad al-Hamoud by text message. He initially agreed to talk and then ignored further attempts to contact him.

A MAN WITH A GRUDGE

It is unknown whether Mustafa Saad al-Din really had a friendship with Ziyad before the case. Ayoub al-Shafi’s role as a hidden hand in the investigation is detailed in his own testimony to IIIM investigators – who used a codename for him — on 20 September 2023. As is his unmistakable animosity toward Walid. He told investigators that Walid was “very spoiled in the directorate” and warned them not to be “fooled by his appearance.” People like Walid, he insisted, were “ambiguous and narcissistic.”

Ayoub witnessed none of the war crimes in Al-Sawana personally. He left the night before ISIS took over, around two weeks before the execution at Suweis Square. He told IIIM that once he arrived in Turkey, he found himself connected to the defected officers’ camp in Antakya, where he met Mustafa several years later and told him the story. Mustafa asked him to find reliable sources who could testify.

“I spent many hours convincing witnesses to talk” to CIJA, he said. Later, when Mustafa complained that the “witnesses have cold feet,” Ayoub confessed he “had to call them again to persuade them to testify to Mustafa,” sometimes for hours at a time.

Almost immediately after his arrest, Walid knew “that Ayoub al-Shafi was behind the case.” Many people said Walid led a group of ISIS fighters to commandeer Ayoub’s home – Ayoub included. Walid says this never happened.

Walid told us the enmity between him and Ayoub goes back more than 20 years, to 2003: “There was a situation in Al-Sawana.”

Ayoub, nearing 30 years old at the time, wanted to marry Walid’s wife’s younger sister, a high-school student. “Ayoub was so insistent,” Walid said, “although the girl did not agree, nor did her mother.” Ayoub faired better persuading other family members, and the engagement went ahead.

But Ayoub needed money for the wedding and an apartment. He asked for a loan from a local businessman. According to Walid, the family found out and terminated the engagement.

Shortly after, the girl went to live with her sister and Walid. “[Ayoub] saw us together, and he thought that I was the instigator for the girl to break off the engagement,” he said. When Walid began working at the mine in 2005, he ran into Ayoub. “He said, ‘I will take revenge on you even though it is the last day of my life. As long as I breathe, I will ruin your life.’ That day, I didn't take it seriously.”

Ayoub al-Shafi did not reply to our message. We were unable to find contact information for Yusef al-Shafi.

CIJA ON THE STAND: “WITNESSES HAD PROVIDED CONSISTENT ACCOUNTS OF EVENTS.”

William Wiley, founder and executive director of CIJA

The case against Walid fell apart under the scrutiny of a trial. The state’s two key witnesses – Ziyad and Mohammed al-Hamoud – failed to convince the judges they were telling the truth. Another witness largely retracted his statements. While CIJA’s evidence was long rejected as a means to prove Walid’s guilt, in the end, the judges used it to exonerate him. The undeniable contradictions between the al-Hamouds’ testimony in court and their statements to CIJA were too great.

Ziyad’s testimony had “changed in several respects during the hearing, not only in peripheral and less decisive parts but also in directly central parts.” There were “serious allegations that the witness deliberately provided false information about Walid al-Zaytun's involvement” in the crimes. The judges noted that this was not only from the defence.

One of the state's witnesses, Issam Rahmoun, a former Baath Brigade member detained by ISIS in Al-Sawana’s “guest palace,” testified via video feed from Germany, where he is a witness in Marastawi’s trial. He knew all of the accused and Ziyad well. “Ziyad Al Hamoud was not at the scene. He was detained,” Rahmoun told the court. “Ziyad could lie about what happened in the square. Many have said that Ziyad has incited people to give information about this.” He also stated that Ziyad al-Hamoud wanted to get to Europe.

CIJA’s Director of Investigations and Operations, Chris Engels, a U.S. lawyer, testified in court on behalf of the organisation. He appeared to have a scant understanding of the details of the case or any first-hand knowledge of the investigation and, at one point, tried reading from handwritten notes.

He confirmed that the “decision to send over the report in question in the case was mainly based on the five interviews held” with Ziyad and Mohammed al-Hamoud, Yusef al-Shafi and Rifa al-Jaseem, and Abdul al-Nabi Ammar (al-Nabi Ammar passed away in July). He made the remarkable declaration that the “witnesses had provided consistent accounts of events.”

Engels commented that he did not believe that the late Mustafa Homs would have fabricated information but did admit that if CIJA had known that two of the witnesses had lied, they “would have delayed the submission of the report.”

“Every day, we receive individuals who want to provide testimonies about people they knew in Syria,” lawyer Anwar al-Bunni, who carries out work into Syrian war crimes, told us. “However, we cannot accept them because there is sectarian bias, family disputes, and often no tangible evidence of a war crime. Not every crime committed in Syria qualifies as a war crime.”

By May, the trial was over. The court released Walid before the verdict was announced. He’d spent 14 months in jail and was interrogated every few weeks. For most of that time, he was in solitary and unable to go outside to exercise because of constant pain from the injury caused during his arrest. “The man was fat, and he hit me hard exactly in the place of the former hernia surgery,” he said.

During his time in Swedish prison, he said he was refused a corrective operation because he was told it was forbidden in pre-trial detention. Prison officers repeatedly refused to provide him with his medication for other medical problems, he said. He went on hunger strike three times. He lost 20 kilos, and his health deteriorated.

On 2 May, the judgment was handed down. Walid was not guilty of the charges. Twenty days later, Reena Devgun announced to the press that the state would appeal the verdict. In August, she withdrew the appeal, releasing a statement that "New information has come to the undersigned’s attention, and the evidentiary situation is considered to have changed. The undersigned cannot foresee a conviction in the Court of Appeal and withdraws the appeal."

She told one news outlet said she had “no regrets.”

Walid said he has not received an apology. We asked the prosecution about the “new information” and about the case in general. They did not respond to The Black Sea’s questions.

Weeks after the acquittal, Devgun suffered yet another blow when the case against former Syrian brigadier general Mohammed Hamo, charged with “aiding and abetting” the Syrian military’s war crimes, also fell apart. In August, she indicted a Swedish citizen on charges of genocide and war crimes against Yazidi women and children in Syria.

Since his release from prison, Walid has tried to rebuild his life. But his business is struggling. “I have a company here; it is still working, and it is registered legally. My partner took care of jobs when I was in prison, but the work is bad nowadays. The economy of the company is not good.”

He recently appeared on Arab television alongside Mohammed al-Ayed and Anwar al-Bunni. During the broadcast, they condemned the charges against him and named Ayoub as the man behind the accusations. “They didn’t target me alone; they provided information to European authorities on over 35 people, most of whom are innocent. Their only ‘crime’ is that they happened to be in Al-Sawana when Daesh entered.”

Walid told us he is trying to appear as a witness for Mustafa Marastawi’s defence in Germany. Both Mohammed al-Ayed and Walid complained to us that the verdict brought new, unforeseen consequences. They and their families are suffering continued death threats online, mostly from Syrians, an inexplicable outcome since the trial generated almost no publicity. “We are now under the pressure of a cyber campaign against us on social media. They accuse us of being with ISIS, which is very dangerous, while no one holds [CIJA and the witnesses] accountable.”

Mohammed believes the attacks are fuelled in some way by CIJA, though he admits there is no supporting evidence. While this might seem extraordinarily reckless, CIJA’s management has gone after critics before. Back in 2020, when OLAF announced the findings into CIJA’s financial malfeasance, a UK professor known for his outspoken views of Western interventions in Syria contacted the organisation with questions about the allegations. CIJA retaliated with an orchestrated “sting” operation, posing for several months as a mysterious Russian figure with valuable information about the company. They gave the story to the BBC and the UK Observer to publicly embarrass and discredit the professor.

Since Walid’s acquittal, CIJA has made no mention of the case publicly. In stark contrast to Chris Engel’s admission in court about the truthfulness of the CIJA’s witnesses, Wiley doubled down in the recent annual report from August, in which he still refers to the three as “members of Daesh.”

“Walid A. has since been acquitted by the District Court in Stockholm – a decision that remains under appeal. While acquittals are often difficult for the victims, especially where evidence remains robust regarding criminal wrongdoing, it is an essential component of the rule of law and a marker of the very democratic values that the Syrian Regime and Da’esh severed with the utmost contempt.”

CIJA refused to answer any of The Black Sea’s questions and called the story all "false allegations."

Editing: Himanshu Ojha, Mina Eroğlu

Translation work: Abir Naeseh

Illustrations: Michelle Urra