Dilovası, Turkey – There is a strange hill just beyond the residential neighbourhoods of Dilovası, an industrial town southeast of Istanbul on the coast of the Gulf of Izmit.

Nestled between the town’s edge and a sprawling coal site, the hill from a distance appears to be covered in grass and shrubbery, with carefully arranged, young pine trees on top. On closer inspection, the land is dead, home to a few withered and thorny plants sprouting from the pale ground.

A few months ago, with grazing land around Dilovası dwindling, Yaşar Aydın, a 55-year-old shepherd living nearby with his family, took his sheep to graze there. After a few days, the sheep got sick and began biting their hoofs until they bled.

Sat on a divan beside her father, mother, and sister in the one-storey house the family built twenty years ago, Yasar’s daughter, Mensure, a strong, 27-year-old woman who helps her father herd the sheep, said they visited the local vet after the flock "started chewing their feet like crazy.”

“He told us that because it rained earlier, maybe the cause is microbes in the soil,” she said. I didn’t understand what he meant.”

It occurred to them that their own skin becomes irritated whenever they come into contact with the hill. “We then realised it was because we were taking them there,” Mensure said. “We stopped for two or three weeks now, and all the itching stopped; the animals are better.”

Another shepherd, living a few hundred metres from the Aydın family, is Kadir Çelik, a chatty old man with great affection towards his flock. When we meet him in July, he was happy to talk, but suffered from acute asthma, which he developed recently, and took frequent breaks to administer medicine from his inhaler.

“We bypass the hill,” Çelik said. “I don’t let the sheep go up there. If they do, they start itching and they bite their feet and wounds appear.”

Shepherd Kadir Çelik says he doesn't let his sheep go up to the dump, otherwise the animals start itching and biting their feet (Petrut Calinescu/The Black Sea)

The Black Sea visited the “hill” in July this year. What we found was not a natural part of the landscape, but a 12,000-square-metre mass of man-made waste, spread all along each side of a small dirt path, next to a stream. After only a short visit to the site, our hands and arms began to itch.

We would later learn why. Samples that we had tested revealed that the hill is formed of tonnes of irritant substance known as glass mineral wool, an insulation used in homes and buildings formed by melting glass fibres with formaldehyde binders at extreme temperatures.

More concerning is what is mixed into the wool.

The tests, conducted by a fully accredited, specialist labs, found significant amounts of three types of very dangerous asbestos, a banned, fibrous flame retardant once commonly used in insulation products, but which is now known to cause cancer and other lung problems. One of the varieties at the site is capable of causing cancer after only a single exposure. The dump has been in Dilovası for more than thirty years. And it seems the municipality tried to cover it up.

The existence of the illegal and lethal dump, never before revealed, is part of The Black Sea’s Toxic Valley project with the European Investigative Collaborations network, which investigated the disastrous effects of three decades of hyper-industrialisation in Turkey’s Kocaeli region, and the small town of Dilovası in particular.

Our research shows how the Turkish state continues to court business to the area, hundreds from the EU, despite a wealth of studies warning that the scale of uncontrolled pollution in the area was causing significant environmental and health consequences for the locals. In 2007, the Turkish parliament even suggested designating Dilovası a “public health disaster zone.”

That the dump site is a serious risk to the local population is beyond doubt, experts said. It is not possible to determine who is responsible for the illegal site without a full, official investigation. But locals’ testimonies and our own research with EIC’s French partner, MediaPart, point to one of the oldest companies operating in the town; today half owned by one of France’s biggest conglomerates.

“I have never seen anything like this”

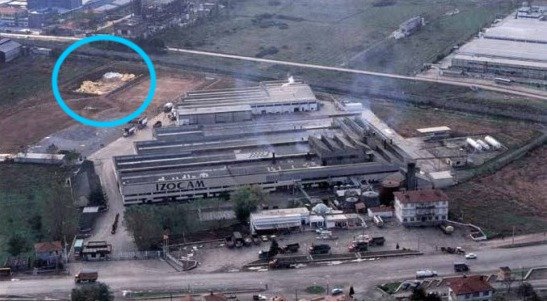

Drone shot of the confirmed dumpsite in Dilovasi, highlighted in red (Medyascope)

There are concerns for the public health of Dilovası residents. Like many there, the Aydın family are sick. In a separate article published last Friday, they explained how they struggle to survive each day with the pollution that affects the entire town.

Mensure has spots on her skin and irregular bleeding in her throat. “I started passing out around six years ago,” she said. “At the same time blood would come gushing from my throat. We went to many hospitals and doctors, but they don’t know what is wrong with me. Now I have spots appearing on my arms out of nowhere.”

Her medical report, seen by The Black Sea, shows a barrage of medical tests, including cancer biopsies. Doctors cannot explain her illness. Kudret, Mensure’s mother, was diagnosed with acute asthma four years ago, at the age of 66. Now 70 years old, she cannot leave the house; going outside brings on attacks. Their 21-year-old daughter, Zozan, was diagnosed with the same problem when she was 18.

“One day, I just couldn’t breathe. It was like my lungs were blocked,” she said. “I leave Dilovası and feel fine. Then I come home and feel worse again.” Zozan’s 5-year-old nephew, who lives next door with his parents, also has asthma.

There is no evidence that the materials on the hill are responsible for the symptoms of the Aydin family or anyone else. But our findings at the dumpsite are emblematic of the relentless industrialisation in Dilovası, barely restrained even today.

In August, a month after we visited the two families, we travelled again to the hill, taking with us Ferudun Demirel, one of Turkey’s top asbestos experts, and owner of ID Industrial Cleaning and Asbestos Consultancy firm. He told us of his “pure shock” at the scale of the dump. He said that in all his decades of experience he had “never seen anything like this before.”

Demirel collected samples and ran tests through several accredited labs, which cross checked the results. Each lab found that the hill was made of glass-type mineral wool, a “dangerous irritant,” Demirel says, and an abundance of discarded fibre cement, used as cladding and roofing material.

This substance, called “fibro,” contained two types of asbestos: crocidolite and chrysotile, commonly known as blue and white asbestos. The third kind, amosite — or brown asbestos — the most lethal kind there is, had contaminated the glass wool. The source of this could not be determined without further, extensive tests, Demirel said.

“Although the majority of the dump is mineral wool,” he said, “several types of waste got mixed here and the material became contaminated by asbestos. These are very dangerous types of asbestos. They are tiny fibres, so they float in the air. They would also mix with soil and water very easily. There is a great risk to the environment and human health.”

“I have never seen anything like this,” he added.

Yücel Demiral, medical doctor and professor of public health from Dokuz Eylül University in Izmir, Turkey, confirmed the health risks of the asbestos found in Dilovası. “It is certain that these are cancerous material,” he said.

“Normally you can conduct certain tests to see how the locals in the area are affected. But at this point, there is no need for tests or waiting. This dump needs to be immediately removed.

“This is unacceptable,” he added.

One major concern is how these substances infiltrate the surrounding area. This can occur via particles in the air or the river that flows from the chemical plants in the hills above, past the dump site and down to the town.

The shepherds know not to get close to the river. Even their animals avoid drinking the water. When they do, they fall sick. “I caught one of my sheep drinking from the river a few weeks ago,” said the shepherd, Çelik. “She got sick that night with heavy diarrhoea. Two days later, she also miscarried. She barely survived.”

Who dumped what?

The adults in Dilovası have known about the dump for decades and some told us they played there as children. Until this week, they knew nothing of the extent of the lethal dangers hidden beneath the soil.

The first clue as to who dumped the illegal waste is in the name the locals give the site. Many refer it as Izocam tepesi — or 'Izocam hill’.

Izocam Trade and Industry, Inc was Turkey's first ever manufacturer of mineral wool products, and is today the country’s biggest, exporting its products to more than 45 countries around the world. The company’s plant, which stands in the centre of Dilovası’s valley, was among the first to appear, back in the late 1960s, when the town was still a lush, green land with no name, few residents, and an abundance of wildlife.

For many decades, Izocam belonged to Koç Holding, the largest conglomerate in Turkey, owned by the wealthy Koç family. But in 2007, it was bought by French multinational, Saint-Gobain, and Kuwait’s Alghanim Industries. Alghanim Industries is a private firm in Kuwait run by the influential Alghanim family. Saint-Gobain is a 350-year-old, Paris-headquartered building materials firm, with revenues of ten of billions of euros. Together they own 95 percent of Izocam. The rest is publicly traded.

In our report last week, we showed videos taken by Dilovası locals of Izocam releasing thick smoke into the town at several points over recent years. In emails to EIC’s French partner, MediaPart, Saint-Gobain claimed the smoke was ‘an extraordinary event.” They also claimed no knowledge of the illegal asbestos site, but fell short of issuing a clear denial that Izocam hill was the company’s work. Alghanim Industries could not be reached for comment.

Journalists help collect samples from "Izocam Hill", which turned out to contain glass mineral wool and asbestos (Petruț Călinescu / The Black Sea)

What is the evidence against Izocam?

The Black Sea investigated the likelihood that the asbestos and glass wool were dumped at the site by Izocam, and our findings show that the case against the company is strong.

Saint-Gobain correctly stated in its email that it has never used asbestos in its mineral wool products. The asbestos in Dilovası is from fibre cement. The way it is mixed and distributed throughout the glass wool on the “hill” strongly suggests that a single culprit is responsible.

"In this area, you have a hill composed of tonnes of mineral wool, dumped in an uncontrolled fashion and mixed with asbestos,” Demirel said. “The fibre cement parts, they’re not big, are mixed with the mineral wool. It’s not just one spot, dumped separately, it’s mixed in in small amounts all over the field.”

Locals we talked with said that the site first appeared in the mid-1980s. “Back then,” Demirel said, “there was no other company producing glass wool” in these quantities.

We asked about the possibility that the materials could be from a customer of Izocam, or the result of a building renovation. For a customer to buy such huge amount and then dump it “just doesn't make any sense,” Demirel said.

A renovation is almost impossible, Demirel said. “In Turkey in the 1980s, this material was used only for roof isolation, not walls. How many roofs do you need for that much glass wool to accumulate? It’s simply not logical to think this would have come from a building; it would have to be giant to make that size of dump.”

“My belief, as an expert,” he continued, “is that this is dump is excess produce, whereby the manufacturer collected all the accumulated excess or faulty waste from production, as well as some other waste from around the factory, the fiber cement, for example, and dumped it all here.”

Demirel’s professional suspicions appear to be independently confirmed by other sources. When asked about “Izocam Hill,” former municipal worker, Ismail Kaya, who moved to the valley in 1980 and later helped establish Dilovası, told us that he knew exactly how Izocam dumped the materials that made the hill.

Between 1984 and 1986, he worked as a contractor for the company, carrying mineral wool products from the factory to the trucks. “There would be faulty product,” he said, “and [Izocam] used to take this outside to a place on the grounds of the factory and dump it.”

“Locals would come and grab it to use in their houses as isolation,” he said. “There was even a black economy where some men would collect this stuff and sell for much cheaper. There were complaints from the real buyers.”

The management ordered the unwanted products and other general waste to be taken away from the plant and dumped on the hill. “The factory needed somewhere easy to dump its waste,” Kaya said. “Back then, the area near the river was completely empty. There was nothing around it. They dumped the stuff there with trucks, and turned it into a hill”

A photo of the Izocam plant from the mid-1980s shows what appears to be a large hole in the ground, full of yellow mineral wool. Kaya confirmed the image is accurate:

We spoke with two more former Izocam employees, who were reluctant to say anything negative about their former company, but did confirm that Izocam first dumped its waste on the factory grounds. Later, they said, trucks took it away. They could not always say where.

One man, an employee from the early 1980s until the mid-2000s, said “the trucks would come to pick up the wool that couldn’t be recycled, was faulty or dirty, as well as the factory’s other waste, and take it away. I knew they’d dump it in trash fields around or bury it, but I don’t know exactly where.”

The other man worked at Izocam for the entire 1980s. “They dumped products in front of the factory,” he said. “Trucks would come and take away the factory waste and product excess, but I think this went to Izaydas,” he said, referring to separate, authorised waste site a few kilometres away. This was closed years later for being too toxic.

Today, “Izocam Hill” is located next to a residential neighbourhood. We calculated the surface area of the dump site to be around 12,000 square metres. There are reasonable suspicions that the land connected to the dump could contain even more waste, hidden beneath the soil.

At the time of the interview, Ismail Kaya and the other former workers did not know that our testing showed the dump contained glass wool and asbestos.

“They disregarded human health,” said Ismail Sami, a local worker, who also runs an environmental association in Dilovası. “Nobody opposed this dump back then either. Dilovası people have been dealing with smog and heavy metals, and now they will be dealing with dangerous waste mixed with asbestos. What else can I say? Those who are responsible should go to hell”

The Dilovası municipality acknowledged it received our questions about the asbestos dump, but had not replied by the time we published.

Close up of the mineral wool (Petruț Călinescu / The Black Sea)

A literal cover up

“Izocam hill” is not simply a decades-old, forgotten crime. Not only has the local municipality failed to hold the culprit accountable, ten years ago it actively tried to cover up the existence of the dump.

After scientist Dr. Onur Hamzaoglu released his 2006 study revealing high cancer rates and endemic respiratory diseases among Dilovasi residents, a Turkish parliamentary commission investigated the town and found that decades of uncontrolled pollution from the industry had turned it into a “public health disaster zone.”

The Turkish government ignored the studies’ recommendations to clean up the area, and continues to incentivise companies to build the area, including many from the EU. But the ruckus Hamzaoglu caused did have one consequence: the Dilovasi municipality knew it needed to hide the dump.

Ismail Kaya said that around 2007 the municipality “started to cover up the dumpsite with soil and by planting trees. Our environmental association opposed this. We told them that they were covering up for the industry. [The authorities] were upset and said we were against the planting of trees.”

Kadir Çelik said he also remembers the area “being covered with soil” and trees by the municipality. But that a few years ago, this dirt slid down from the hill and exposed the mineral wool waste underneath. “Look,” he said, digging the ground with a stick, exposing a yellowish cotton-like material. “More and more Izocam. Endless.”

While the dumping of asbestos and glass wool took place before Saint-Gobain or Alghanim bought the company, lawyers consulted by The Black Sea said that this makes little difference under Turkish and EU law. Izocam retains the corporate and legal liability, they said, and this was inherited by both parent firms. Saint-Gobain filings in France show it has direct control of Izocam’s operations.

One of the lawyers, who asked not to be named because he works in the corporate sector, said that the parent companies “cannot say they didn’t know about [the dump]. They took over the company; ownership is irrelevant.”

Another lawyer agreed: “The court has to find liable whoever is the company now,” she said. “The parent companies can try to defend themselves by saying they didn't know about this dump, but companies are bought in their entirety, both the positives and negatives. Liability remains.”

Turkish regulations stipulate that the dump might constitute an environmental crime. The head of the Chamber of Environmental Engineers, Baran Bozoğlu, said that the Turkish Ministry of Environment and Urbanisation “should take administrative action, and citizens should file an official complaint to the prosecutor’s office.

“If this is an environmental crime, criminal law should take over. At the end, both criminal and administrative sanctions could be handed out.”

The court can technically force Izocam to clean up and rehabilitate the dumpsite, which would likely incur huge costs for the company. But environmental lawsuits are not often successful in Turkey. French environmental law is robust at home, but more vague when dealing with foreign operations.

Associate professor of public law at Tilburg University, Daniel Augenstein, an expert on corporate responsibility and human rights, said that residents could sue in France where Izocam’s owner Saint-Gobain is headquartered.

“If the dump is toxic, this also becomes a matter for criminal law. [Saint-Gobain] could be held liable, but this depends on what the French law says.”

Civil and criminal complaints are possible in France, experts say, if the site endangers human life or violates environmental laws.

Go to the Toxic Valley project page

This reporting was supported by JournalismFund.eu

Images and text not subject to Creative Commons