In 1998, an American cattle farmer from Parkersburg, West Virginia, named Wilbur Tennant, was looking for a lawyer. Tennant’s cows were dying, one by one, until the death toll reached over one hundred and fifty. For more than a year, he’d witnessed them become distraught as they bled from the nose and foamed at the mouth before succumbing to a range of inexplicable diseases.

The Tennant family farm was located several miles outside Parkersburg. Beside his property ran the Dry Run Creek, which flowed past the fields where the cattle grazed, and one day, a white, soapy foam gathered on the surface. Tennant, convinced that there was something in the foam that was making his cows sick, ventured up the creek and discovered a discharge pipe spewing a green-coloured liquid. The pipe connected to a landfill owned by DuPont, the multibillion-dollar inventor of Teflon, and had a strong presence in Parkersburg.

Tennant approached Robert Bilott, an environmental lawyer and partner in a large law firm who typically represented corporate clients. Though he worked exclusively for the other side, including at one point with DuPont, Bilott took the case. He later told the New York Times he did so as a favour to his grandmother, who had lived in Parkersburg, where Bilott had spent summers as a child. Since taking the Tennant case 25 years ago, his career as a lawyer has been devoted to exposing the dangers of per- and polyfluoroalkyl, more commonly abbreviated to PFAS. One lawsuit at a time, Bilott has exposed the extent of an unprecedented pollution and global health threat which was covered up by the industry for decades.

What began with Tennant became a class action lawsuit of 70,000 Parkersburg residents whose drinking water was contaminated by the DuPont chemical plant. The case that started in 1998 was settled in 2017. Bilott reached a $671 million settlement.

More than three decades after Wilbur Tennant met Robert Bilott, the European Chemical Agency — ECHA — is proposing an EU-wide ban on the entire group of PFAS, more than ten thousand chemical substances. Regulators in Brussels and across Europe are now directly pitted against a global PFAS-reliant industry and lobby determined to defend their profits.

For Bilott, this was unsurprising. He saw the same playbook in the US when he first went up against DuPont. “It was incredibly difficult,” he told The Forever Lobbying Project. “You know, this was a very carefully coordinated misinformation campaign that had been very well-planned, very well orchestrated by companies with a lot of resources and a lot of very well-placed, highly placed people.”

Bilott himself was confronted with one of the industry's primary lobby strategies: manufacturing doubt. “They were trying to portray me as somebody who was making things up, as if I was creating fear where there wasn’t any.” Bilott stuck to the facts: “I kept going back to the company's own documents, the statements that their own scientists, their own lawyers were making, what the companies themselves were saying – and eventually the truth came out.”

This is the story of how two big U.S. chemical companies, 3M and DuPont, had developed and sold a miracle but potentially lethal family of chemicals and then concealed their health and environmental risks for decades, resulting in the global spread and proliferation of PFAS, which have come to be known as “forever chemicals”.

SECRET PUBLIC HEALTH THREAT

In the early 1950s, the US company 3M began selling the chemical PFOA to DuPont to produce Teflon. What the company did not tell DuPont was that a 3M scientist had carried out testing on mice and found that this perfluorooctanoic acid accumulated in their blood. As DuPont's Teflon production gained momentum, 3M discovered another versatile use for its miraculous chemical and began selling Scotchgard and Scotchban, which protected materials against water and stains. Over the following decades, 3M and DuPont products became indispensable in millions of homes and workplaces. Their toxicity was a closely guarded trade secret. It would remain so for decades —until Wilbur Tennant's cows began to get sick.

In 1999, Bilott filed a federal lawsuit against DuPont in Parkersburg. After months of working on the case, Bilott discovered a letter from DuPont to the Environmental Protection Agency that mentioned the acronym ‘PFOA.’ When he asked DuPont for further documentation on the substance, the company refused. What Bilott didn’t know at that moment was that he had just unearthed evidence of a chemical that nobody but a few company insiders knew existed.

A 2000 court order forced DuPont to provide all documents relating to this mystery chemical, boxes and decades of confidential studies and internal correspondence. Bilott was slowly piecing together a bigger picture: “Digging through all these documents and trying to piece this story together, it really took a while to understand that we were dealing with something that went way beyond just one farm in West Virginia,” he said.

Bilott now had access to documents that revealed that 3M and DuPont had known since the beginning of the production of PFAS that the chemicals could potentially make their way into the blood of every citizen in the United States and, once there, remain and accumulate. Six years after the 1950 study on mice by 3M, researchers at Stanford University discovered PFAS bind to proteins in human blood. In 1961, a different scientist at 3M alerted the company to his findings that PFAS chemicals enlarged the livers of rats and rabbits. Two years later, an internal technical manual distributed at 3M declared PFAS to be toxic. Another DuPont study found liver damage and spleen enlargement from PFAS.

Over the next decades, a slew of internal, unpublished studies by scientists at 3M and DuPont revealed devastating health consequences on anything PFAS touched: mice, rats, rabbits, dogs, monkeys. The companies, however, remained silent.

“UNPRECEDENTED IN SCOPE AND SCALE”

Unfolding in the documents before him was a story of decades-long deceit: “I really did not believe that something like this could be going on, particularly in the United States in modern times. Not only could this contamination be going on, but that it could be actively covered up.” Bilott’s experience working for corporate clients, including large chemical companies, did not prepare him for what he discovered: “It took me so long to accept that what I was seeing was actually happening because this was something I had not seen occur with other companies.”

The information about PFAS and their effects on humans that 3M and DuPont kept from the public had piled up for decades. Among the documents was internal correspondence from the beginning of the 1970s showing DuPont scientists warning that PFAS was “highly toxic when inhaled” and warning 3M that there was no safe level of exposure to PFAS in food packaging.

In 1977, 3M found that PFOS, the chemical in the company’s Scotchgard product, was “more toxic than anticipated.” When, in the early 1980s, the companies learned that PFAS could damage the eyes of developing fetuses, 3M and DuPont reassigned their female employees “For a long time, I really couldn’t understand why this was really happening. I was trying to assume there must be some other explanation. It was incredibly disturbing to realise we had a massive public health threat that was going completely unrecognised,” recalled Bilott.

Soon, 3M noted the potential harm that PFAS could do to the immune system and began to document rising levels of PFAS in the blood of their workers. Another 3M study, in 1989, found elevated rates of cancer in workers. By 1992, DuPont also discovered the same problems with cancer among its own workers. Neither company informed the public or authorities of potential risks.

“The companies were not warning anybody that there was any harm here because they kept telling the employees and the public and anybody that would ask that these chemicals present no risk of harm,” said Bilott. “So even if it's in your blood, it's nothing we need to be worried about.”

By the late 90s, as Wilbur Tennant’s cows were dropping dead, 3M scientists proved that PFAS was capable of moving through the food chain. “Around the time, there were some internal discussions. There were some scientists within 3M that were raising some concerns.”

What reads like a thriller became the basis for Dark Waters, a Hollywood production from 2019, which starred Mark Ruffalo as the U.S. lawyer Robert Bilott. “It took having movies like Dark Waters… to get this story out to the rest of the world,” Bilott said.

The Forever Lobby Battle

The cynical and deceptive campaign to obscure the science and hide the dangers of PFAS is reminiscent of the likes of Big Tobacco.

For Bilott, the PFAS cover-up had even greater consequences. With tobacco, he said, “the extent of the problem is limited to the people who were smoking. But here you're dealing with contamination of the entire planet. So, it's really, truly unprecedented in scope and scale.”

“I firmly believe, based on the documents I've read over the last 25 years, the science I've seen, the information that's out there, this is a real public health threat. Everybody is impacted by this. And we do know enough now to be taking the steps that are necessary to stop this and to begin protecting people from this going forward.“

Today, there are thousands of cases related to PFAS moving through the U.S. court system. 3M faces about 4,000 lawsuits in the U.S. over PFAS contamination. By 2017, DuPont had settled over 3,550 lawsuits for over $600 million. By 2023, more than 15,000 claims had been filed against DuPont and 3M. The two companies have paid billions in settlements and damages to governments, municipalities, and water utilities in the U.S. over the past 25 years. Still, after decades of revelations and further scientific findings, the companies dispute the potential harm of their chemicals and request further evidence.

PFAS, explained Bilott, do not exist in nature but are completely man-made: “So when we find them in the water, in the soil, in the air, in people, their fingerprints, [we can trace them] back to this small group of companies who created these chemicals. So we do know who's responsible here.”

This provides a high incentive for companies to drag on legal battles for years, he added, “to avoid that responsibility and to try to move money.” Because “when you're talking about having contaminated the whole planet, the potential liability is so large and the amount of money that could be involved in addressing this problem is so big.”

In the European investigation, the Forever Lobbying Project, journalists and scientists have estimated the potential costs of cleaning up PFAS in the environment. If PFAS emissions in Europe stay at their current rate, the estimated costs for the next 20 years alone amount to over €2 billion. In another study by the Nordic Council of Ministers from 2019 on the ‘Costs of inaction’, the costs to public health in Europe due to global PFAS contamination are estimated at €52 to €84 billion annually.

To create scientific evidence for the harm of PFAS to the public that the companies still claim is not available, Bilott filed a new lawsuit in 2018 against several PFAS manufacturers on behalf of anyone who has PFAS in their blood. “We are trying to bring claims for people who have these chemicals in their blood simply to get the studies and the testing done to tell us what will that mix of chemicals do while it's there in our blood circulating, building up, becoming a ticking time bomb over time.”

While the PFAS legacy began with 3M and DuPont, today, there are many more PFAS manufacturers and users of PFAS chemicals. In 2023, The Forever Pollution Project, a twelve-month investigation by 16 European newsrooms, set out to map PFAS pollution across Europe. In Europe alone, 20 PFAS producers and over 200 PFAS users were identified.

In Europe, legal disputes over PFAS are still in their early stages. The largest case has been ongoing in the Netherlands and Belgium since 2021. Here, a Chemours facility (formerly DuPont) has been sued by the local governments as well as residents for discharges of PFAS in wastewater, pollution and contamination of the waters and fish, as well as health effects on citizens. In some European countries such as Italy, France, Germany and Sweden legal action has been taken against PFAS manufacturers or users for contamination.

It has been estimated that around 140 industries worldwide are facing PFAS lawsuits today.

In 2022, 3M announced that it would cease production of PFAS and phase out the use of PFAS chemicals in all its products by the end of 2025. However, 3M told ProPublica that 16,000 of its products still contain PFAS today.

The Forever Lobby Battle

In 2023, five European countries, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany, proposed a global PFAS ban restricting all chemicals of the PFAS class in Europe to ECHA, the European Chemical Agency. Since then, industries from all across Europe and the world have argued against a possible regulation of PFAS in Europe. Some of these companies are also from Turkey. The journalists of The Forever Lobbying Project have collected and analysed, with the help of scientific experts, the arguments industry actors have used to shape the debate and start a disinformation campaign. The aim: To delay and water down a European PFAS restriction.

“It's the same arguments we've been seeing here in the US and I've seen play out worldwide now for decades,” said Bilott. Two of the main arguments of the industry are that PFAS are essential for many production processes and products and that the economic impact a ban could have on European industry and its businesses would be substantial. “The reality is”, explained Bilott, “that this was a very purposeful strategy to push these chemicals into all of these different aspects of the economy so that you have this argument now.” When regulators finally caught up and realised the public health threat that had been hidden for decades “suddenly you're able to say, this is too big to regulate. That's been a very effective strategy. And we're seeing it simply repeat itself again.”

Wilbur Tennant settled with DuPont in 2001 for an undisclosed sum. He did not live to see how the lawsuit he initiated against the company would grow to help thousands of plaintiffs obtain a settlement of over $600 million in 2017 that prompted thousands more cases that helped bring to light a global public health risk and legislative reform. The farmer died in 2009 at the age of 67.

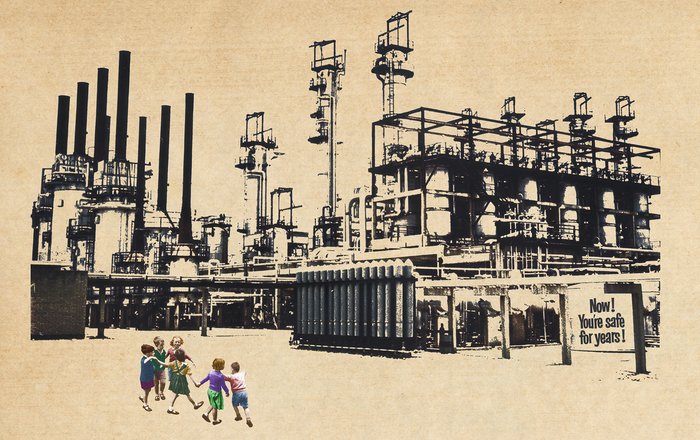

Opening image: Stéphane Horel© (Dark Waters, 2023)

Interview with Robert Bilott by Emilie Rosso

Edited by Craig Shaw and Himanshu Ojha

The project received financial support from the Pulitzer Center, the Broad Reach Foundation, Journalismfund Europe, and IJ4EU.

Website: foreverpollution.eu.