We investigate how European Funds were used for projects to develop human resources in Romania, where 3.5 billion euro of EU money was available to spend between 2007 and 2013

The destination of the cash included suspect purchases of premium vehicles, money given to political appointees and alleged kickbacks

Projects designed to find people work resulted in half a million euro spent on a scheme which created only six new jobs

The beneficiaries of projects hit by scandals have continued to attract EU funds for the next round of financing for human resources projects from 2014 until 2020

A top-of-the-range Mercedes Benz. Value: 45,000 euro. Included in the package were a host of features such as parking assistance, heated front seats, an improved steering wheel and gearshift, as well as interior lighting.

The buyer: a private University in Bucharest called Titu Maiorescu.

Who was paying for the vehicle?

The European Union member states.

This was part of an EU-funded project contracted by the Romanian government to promote the development of small and medium businesses, where the university was a partner.

The total budget of the project was over 17 million RON (four million euro), including a 15.7 million RON (3.6 million euro) EU grant through the Sectoral Operational Program Human Resources Development (2007 to 2013), which is known by the acronym of SOP HRD in English and POSDRU in Romanian.

Although this money comes from EU member states through the European Social Fund, the program was overseen by the Romanian Ministry of Labor, and designed to help people find work, learn new skills or run their own business.

It is unclear how a premium German vehicle for an educational institution can help desperate Romanians find work and, when we contacted Titu Maiorescu University to ask for their response, they refused to answer.

This purchase was red-flagged by the Romanian Court of Accounts, a public body which monitors state spending, in its 2012 report.

Human resources projects are a major target for billions of euro in EU financing, but their success is tough to assess, as training does not end up with a renovated school or a new road. The results are mostly intangible.

This created issues in how the grantor for the first round of financing, the Ministry of Labor, could monitor such projects, and in 2010, the Court of Accounts noticed a problem. In the Ministry, one section of the Managing Authority of SOP HRD which evaluated the success of the projects was not communicating with another section which assessed the contracts. In other words - there was virtually no oversight.

“There is a risk of contracting projects with unfounded, unrealistic budgets, involving ineligible or non-achievable objectives,” the Court’s report stated.

On-the-spot checks on projects by the Managing Authority were not happening, or were delayed, while their monitoring reports were sent late, creating a risk that beneficiaries of EU grants could be asking for ineligible expenses.

Not only this. There was an issue of project duplication, even plagiarism. The Court gave the example of projects which promoted rural sustainability with “the same name, same objectives and same value, submitted by the same beneficiary”. The report also detected hourly spending by projects on experts, who “worked” for up to 24 hours per day - a physically impossible task. For three years, the Court showed that monitoring of the contracts did not cover the issue of whether the winners of bids had conflicts of interest.

The SOP HRD management system was out of control.

Fraud was possible. Tasked with investigating the potential cases of malfeasance in Romania was the National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA). Upon our request, the DNA could not give the number of its probes on SOP HRD, but several dozen are public.

The most severe case involved the former Minister of Labor, Family and Social Protection, Ioan-Nelu Botiş. The project ‘Chance to Dignity’ developed by the ‘Euroactiv Partnership’ Association in Bistrita, north Romania (where Botiş is an MP), was approved after Botiş’s appointment as Minister in 2010. Part of his new job was to manage EU funds.

However the Employment Agency of Bistrita-Nasaud County, managed by Botiş, was a founding member of ‘Euroactiv Partnership’, according to the National Integrity Institute (ANI), which monitors public officials’ wealth declarations. Moreover, the wife of Botiş was on the ‘Chance to Dignity’ project team.

Botiş resigned as minister in April 2011, but escaped any criminal charges.

This lack of oversight led to a number of suspect cases that we now examine - including alleged kickbacks to bureaucrats, contracts to Ministers, their relatives and high-level political connections, as well as projects greenlighted with near-zero ambitions. We also show what happened to individuals involved in alleged cases of fraud, and how associations connected to past scandals continue to win money from the European Union.

This is how EU funds are spent in Romania.

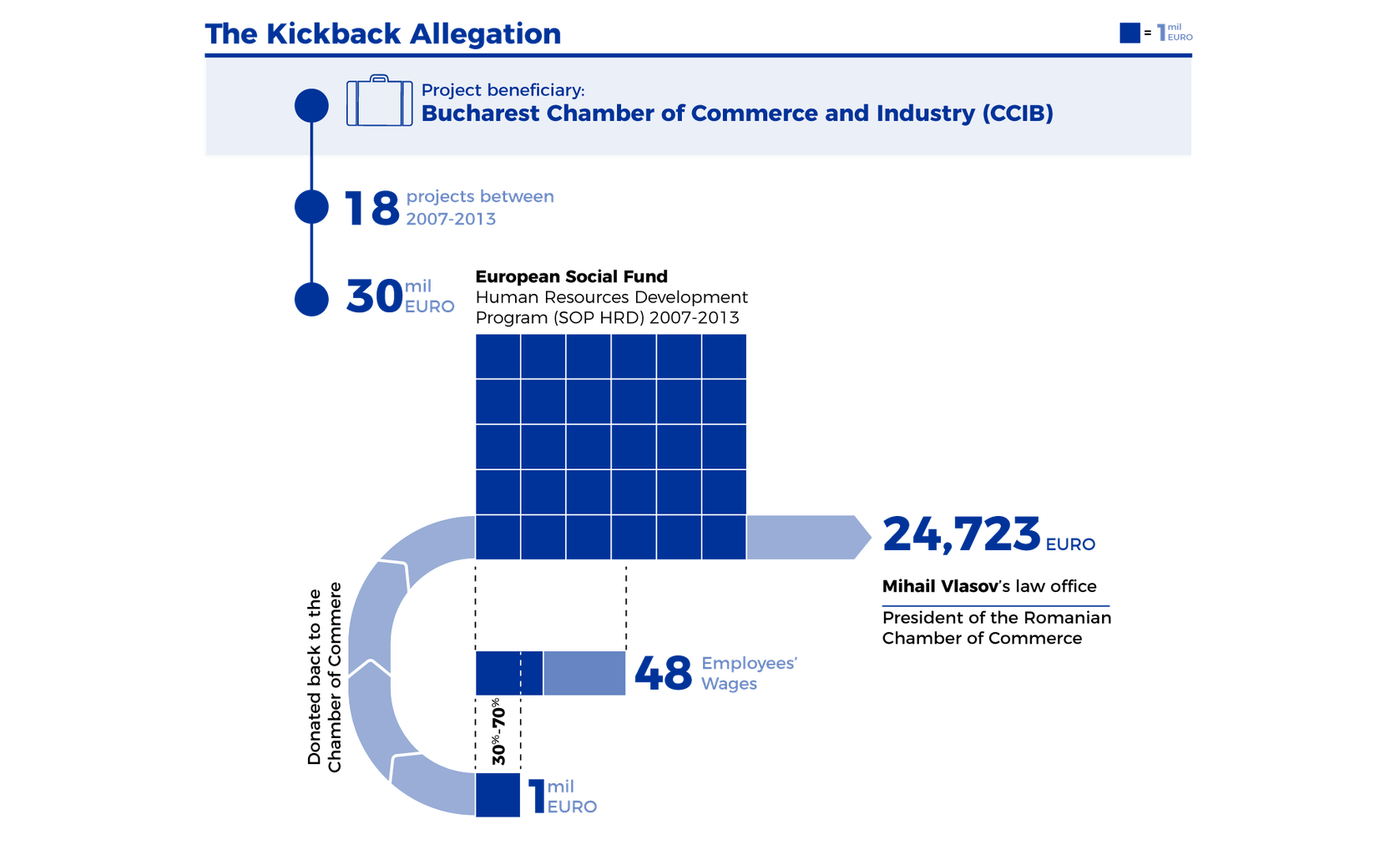

Project One: The Kickback Allegation

For the senior management of the Bucharest Chamber of Commerce and Industry, known as the CCIB, an NGO that promotes trade and investment, the new SOP HRD funds became an opportunity to plug financial holes in their association’s budget.

The way they did it was criminal, claims Romania’s National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA), the government agency tasked with investigating graft and financial crimes.

Over the 2007 to 2013 funding period, the chamber successfully applied for 18 projects through SOP HRD, winning more than 30 million euro in grants. Despite the huge amounts of cash flowing through the company from the EU, the chamber had financial problems and struggled to pay its debts.

In 2013, the anticorruption agency launched an investigation believing they had evidence that senior figures at the CCIB had implemented a bizarre kickback scheme to generate extra money for the organisation.

The scam, DNA prosecutors said later in court, involved forcing chamber employees hired to implement the EU projects - 48 out of a total of 58 working at the NGO - to sign “sponsorship” contracts in which they agreed to pay a ‘tribute’ of between 30 and 70 percent of their wages back to the CCIB.

Once they had the signed contracts, the chamber excluded the cash from the workers’ wages. If any employee dared to ask for the money they were owed on paper, or refused to sign a ‘sponsorship’ contract in the first place, they risked being fired.

Three workers did kick up a fuss, however, and the CCIB managers slashed their working hours and dropped them from the EU projects until they resigned. The DNA called this “abusive dismissal”.

Between September 2010 and March 2012, the CCIB attracted sponsorship of four million lei - around 920,000 euro - almost all from employees, plus a small amount from companies. The money went to the “patrimony” of the CCIB, a fund controlled by the bosses Dimitriu and Mihuț, which should have been used by the CCIB to sponsor culture, art and sport.

In October, 2014, the National Anticorruption Directorate announced that it had completed its criminal investigation and was indicting CCIB president, Sorin Dimitriu, as well as the organisation’s general manager, Gabriel Dan Mihuț, counselor, Gabriela Dumitru, and economic director, Laurentia Vasilescu.

Dimitriu was charged with setting up an organized crime group, abuse in service, and fraudulent use of information to obtain EU funds. He was also indicted, along with Mihuț and Dumitru, for designing, organising and implementing the scheme to pilfer large parts of their employees’ wages, while Laurentia Vasilescu was accused of committing offences against the financial interests of the EU.

All deny a wrongdoing.

The investigation into the CCIB also unearthed evidence of the involvement of Mihail Vlasov, president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Romania (CCIR).

Earlier this year, Vlasov was sentenced to nine years in jail for embezzling, along with his daughter, millions from the CCIR budget.

The agency claims that the CCIB paid Vlasov 110,000 RON - 25,300 euro - from the funds it was bilking from its employees, which in December 2010, already amounted to 209,065 RON [48,000 euro].

From a CCIB bank account with the title ‘Various receipts’, on 16 December, 2010, around 24,723 euro was paid to the personal law office run by Vlasov.

This is not the only case against the CCIB. The chamber is accused of presenting false statements to obtain financing for two EU-funded projects, including the failure to mention a 240,000 euro debt to the state. In August 2017, the DNA sent this case to court.

Sorin Dimitriu was again hauled up in front of a judge, this time for “misusing or misrepresenting of false, inaccurate or incomplete documents to wrongfully obtain” EU funds.

Economic director at the time, Laurentia Vasilescu, and Gabriel-Dan Mihuț were also charged with related offences. As a follow up, the Ministry of Regional Development and Public Administration asked for 48.8 million RON (11.2 million euro) back from the Chamber.

The trials are ongoing.

Despite his personal involvement in such controversial actions, Sorin Dimitriu remains president of the CCIB.

”The case is still in court and there's no verdict, therefore Sorin Dimitriu will issue no comment on the matter,” said a spokesperson for the chamber. ”However, Dimitriu relies on the not guilty until proven different principle and believes that justice shall prevail.”

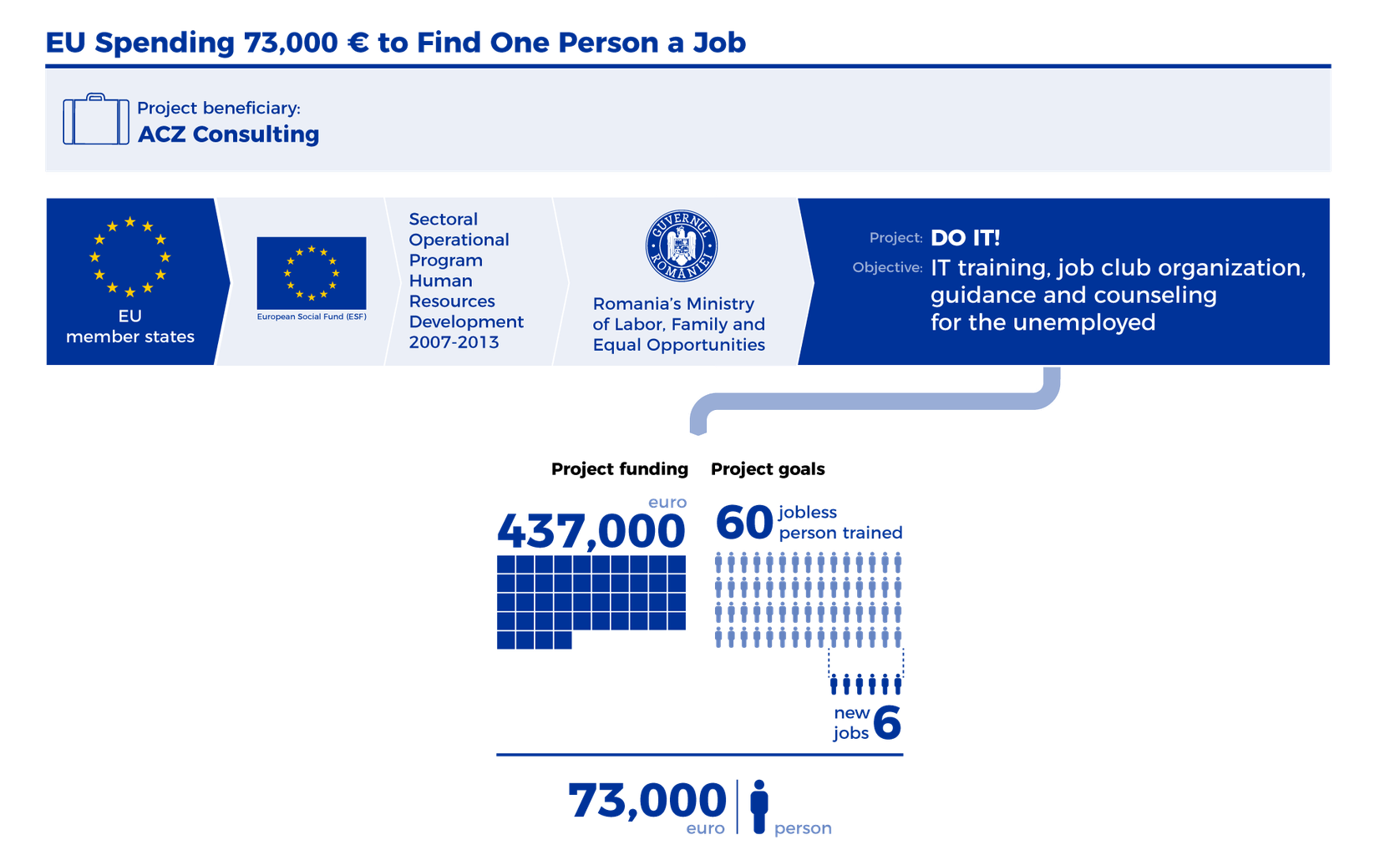

Project Two: 70,000 euro to create one new job

A Nissan Juke SUV bought with EU cash for the beneficiary of a training project alarmed the Court of Accounts in its 2012 report.

This obscure purchase was in the budget of a scheme to train over 60 unemployed in IT skills in the counties of Valcea and Dolj.

The report stated: ”In the case of a project aimed at IT training, guidance and counseling for the unemployed, the purchase of an SUV passenger car... is unnecessary in relation to the results sought.”

The Regional Intermediary Body (OIR), which monitors such EU projects, also argues that buying cars through a hire-purchase scheme with EU funds ”is a frequent practice” in Romania.

Although the project is not identified by the Court of Accounts inspectors, our research indicates that it was called: ‘DO IT’.

This 0.46 million euro project was majority-financed through SOP HRD between 2010 and 2012. A small contribution to ‘DO IT’ came from ACZ Consulting SRL, the project’s beneficiary, based in the western city of Craiova.

This project also shows a textbook example of a problem with the design of human resources projects - a lack of ambition. Nothing here seems to be fraudulent or illegal, but reveals a limited scope in the beneficiary’s aims.

‘DO IT’ offered free training in web design and IT programming to 60 jobless adults, as well as the opportunity for them to participate in ‘job club’ sessions with potential IT sector employers. It also aimed to award a state-accredited training certificate - called a CNFPA - to at least 96 percent of the participants. As a major objective, the project claimed it would ensure ”access to the labor market” or to a business start-up for ”ten percent” of the members of the target group.

This is an ambition the project manages to achieve.

The results of ‘DO IT’ are as follows: the number of trainees who have found a job within six months of training: four.

The number of trainees who have been self-employed: two.

That is six people. Ten percent of the 60 trainees.

The total cost of the project was 1.9 million RON (around 400 thousand euros), so, it could be argued that, on average, the scheme spent 300,000 RON per person to find work. This translates into 73,000 euro for each job. To put this in context, in 2012, the minimum wage in Romania was 162 euro per month.

SOP HRD also granted cash to ACZ Consulting for almost identical IT training projects called ”ACTIV” and ”ANTRINFO”, each financed with 1.4 million RON (0.32 million euro). Both websites, proiect-activ.ro and proiect-antrinfo.ro, have the same design. The target numbers in the project are also the same: both aimed to assist 290 people in training, and find 35 people a job.

Due to these similarities, the question arises as to whether the two projects have something else in common.

Their websites hint at an answer: at least two people, according to the photos posted on both ”ACTIV” and ”ANTRINFO”, are present in both projects, dressed in the same clothes, and in the same location, on what could even be the same day.

We contacted ACZ Consulting to talk about these issues, and Cristina Cojoaca, one of the project managers, told us that ”everything was fine”, and promised to get back to us for further comment, which had not happened when we went to press.

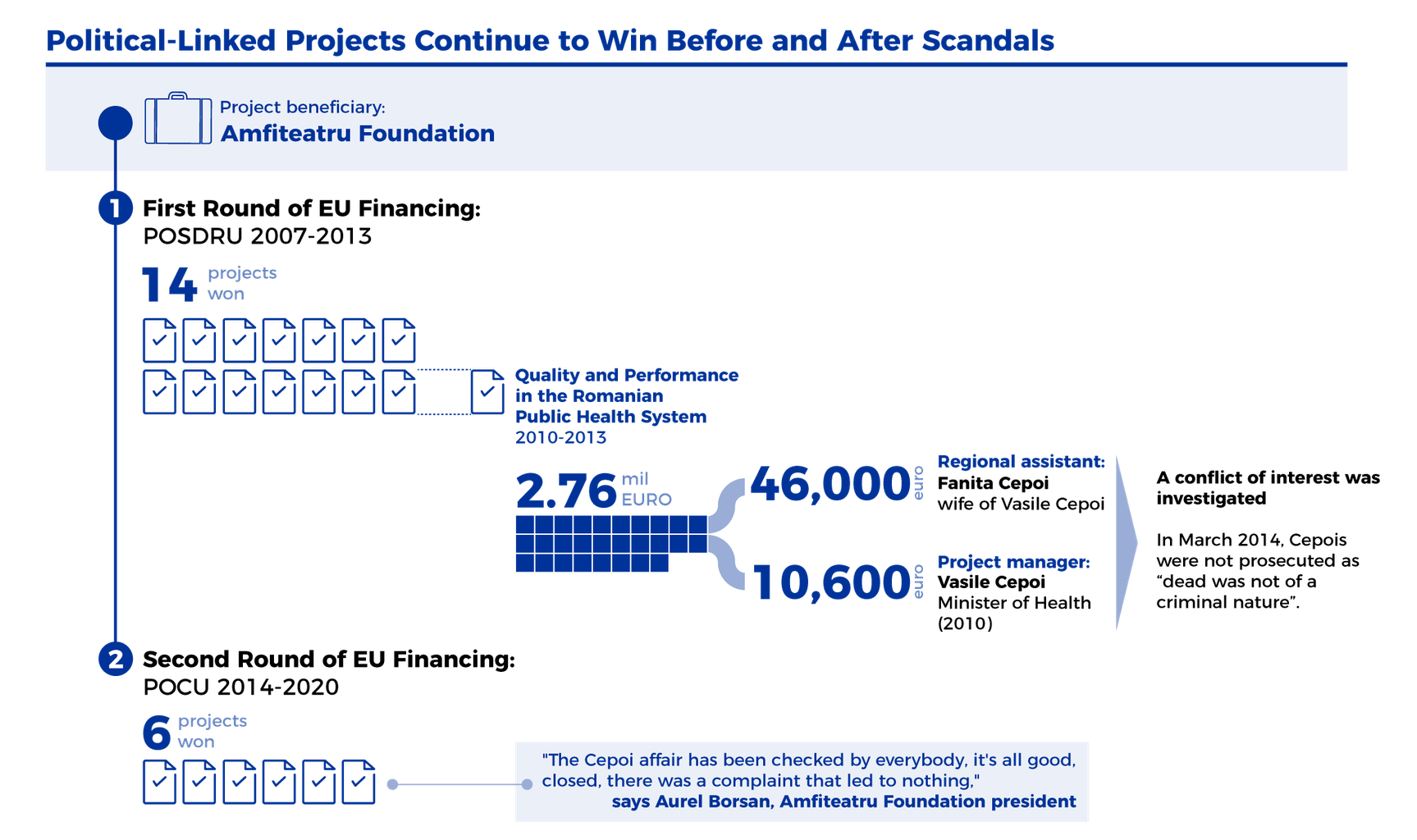

Project Three: Winning EU funds before and after scandal

EU financing for human resources projects continues to flow to companies even after they have been linked to prosecutions involving the dismissal of Ministers.

The Amfiteatru Foundation is one of the largest beneficiaries of SOP HRD funds, and also benefits from its successor for the 2014-2020 period, the Operational Program Human Capital (OPHC, or POCU in Romanian).

One project became interesting for the authorities: ‘Quality and Performance in the Romanian Public Health System’. The amount of EU funding for this 2010-2013 project was almost 12 million RON (2.76 million euro), and the beneficiary was Amfiteatru, with a main partner in the Public Health Directorate (DSP) in Iaşi. The director of DSP Iaşi at the time of signing the partnership was Vasile Cepoi, who became Minister of Health in 2012, while the program was running.

In 2010, Cepoi occupied a number of roles in ‘Quality and Performance in the Romanian Public Health System’. At first he was project manager, followed by project director for editorial and research activities, and then quality audit trainer. In this last position, Cepoi obtained 150,000 RON (approx. 36,000 euro). From December 2010, Cepoi's wife, Făniţa, was employed in the project as a regional assistant, and earned over 31,000 RON (approx. 7,400 euro) by March 2013.

As a result of the financial relationships between Amfiteatru and the Cepoi couple, the National Integrity Agency (ANI), which analyses wealth declarations of MPs, reported a ”conflict of interest” and ”crimes against the financial interests of the European Community” in September 2012, when Cepoi was Minister.

However, in March 2014, the criminal case was closed without Cepoi facing prosecution. The Iaşi Court of Appeal declared there was nothing criminal to pursue.

”It was a false denouncement,” says Cepoi, ”and I quit. Someone denounced me to the National Integrity Agency when I became a minister. Nothing happened before that, and the scandal broke afterwards.”

This scandal did not prevent the Amfiteatru Foundation from winning further projects funded by the European Social Fund. After the expiration of the SOP HRD program, Romania opened the second round of financing, OPHC. Here Amfiteatru was awarded for at least seven projects on ”integration”, ”entrepreneurship” and ”competitiveness”.

Today the Amfiteatru Foundation is confident there is nothing at fault.

”The Cepoi affair has been checked by everybody, it's all good, closed, there was a complaint that led to nothing,” says Aurel Borsan, Amfiteatru Foundation’s president.

”Everything was OK. Even the European Commission checked it and decided it was alright.”

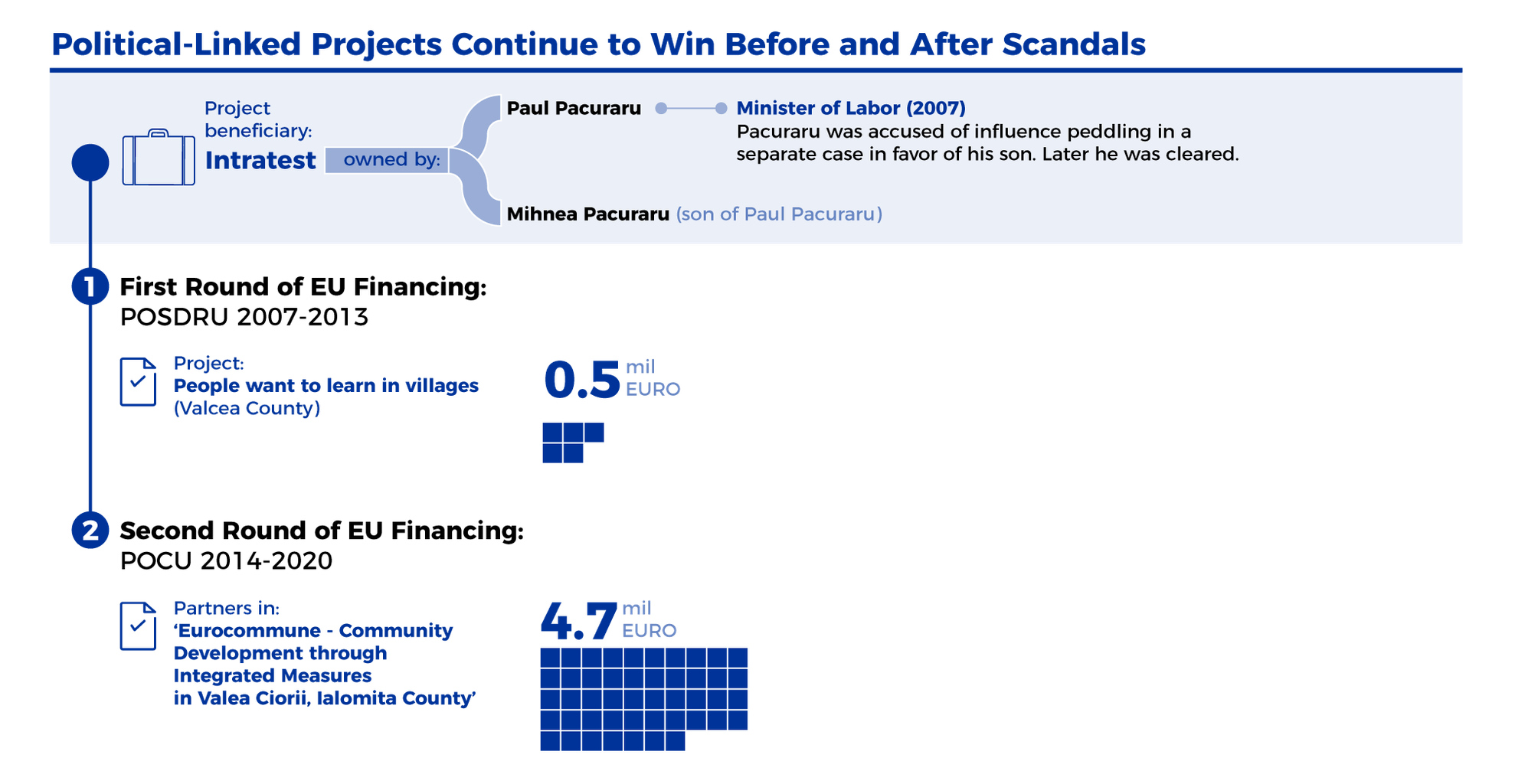

Another company which accessed SOP HRD funds before and after a high-profile scandal is Intratest SA.

One of its projects in Valcea county was called ‘People want to learn in villages’, financed with over two million RON (approx 0.5 million euro) from the EU. Intratest is owned by the father-and-son team of Paul and Mihnea Păcuraru, and was previously run by Mihnea alone. Paul Păcuraru was Minister of Labor between 2007 and 2008 and his Ministry was responsible for granting EU funds through SOP HRD. When we contact Mihnea Păcuraru to ask about this project, he tells us it is ”too old for me to remember.”

Romania’s National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA) investigated Mihnea’s firm in December 2008. According to the DNA, on 3 June 2007, the National Liberal Party (PNL) MP Dan Ilie Morega ”promised” Minister Paul Păcuraru support for his son to obtain public contracts for training staff in coal-power station companies Rovinari and Turceni, and the National Company of Lignite Oltenia. Thus, Păcuraru put Morega in touch with his son.

A few years later the judges acquitted Morega and Păcuraru because prosecutors could not prove that Morega had used his influence to ensure the contracts were won by Mihnea.

Since then, Intratest has continued to be successful in winning European Union funds. At present, Intratest is a partner in a giant project funded by OPHC worth 22.5 million RON (4.7 million euro).

The project is called ‘Eurocommune - Community Development through Integrated Measures in Valea Ciorii, Ialomița County’, training 350 people at risk of poverty and social exclusion. The course offers trainees an initial five RON/per hour in cash, and, once the trainees have qualified, each will ”receive a prize of 1,500 RON” - about 321 euro.

Project Four: Boom and Bust for European-financed NGOs

The finances of an enterprise that wins European funds can also be an indication of something irregular. If an NGO or company reports a small level of business before receiving grants, sees the size of its business balloon during the financing period and then shrink when the projects end, this organisation fails the sustainability test. It looks as though the grantee exists only to absorb EU money.

In this respect, the example of Operations Research SRL is worth examining. Three companies in Romania claimed this name, one in Ialomița County, another in Bucharest and a third in Cluj. The first to be founded, in Ialomița, still exists. In Bucharest, Operations Research ceased to function last February, and in Cluj, the company grew year on year until 2015, before its business fell dramatically. Its figures for the last fiscal year, 2017, were not even recorded to the Ministry of Finance.

The possibility is that such a company was created to absorb EU funds, and then closed when those EU funds were no longer available. Such cases are common with companies that have managed SOP HRD funds. With Operations Research SRL, the most profitable SOP HRD projects took place in 2014 and 2015.

The company attracted further controversy for its payment practises. The first project of Operations Research SRL started in 2010 with a budget of over five million RON (over 1.2 million euro). This was ‘Cityaudit.ro - Online Interactive Training and Information System in Marketing and Business Tools for Entrepreneurs’. According to its official description, the project’s aim was to encourage entrepreneurship by creating an ”interactive online analysis of socio-economic data called cityaudit.ro” to help develop business partnerships across the country. This means a website.

Today cityaudit.ro does not work. Moreover, according to its web-pages indexed by archive.org, cityaudit.ro was never what it proposed, but at most a collection of courses and other seemingly random information on laws and finances.

However, Operations Research SRL boasted an effective marketing campaign: not only did it gain extensive promotion in local publications in the northeastern cities of Romania, but the company attracted a serious partner.

This was the 150 year-old ‘Alexandru Ioan Cuza’ University of Iaşi, the first university founded in what would later become Romania. But in a report on the project’s results, the university states that, towards the end of the project, Operations Research SRL ”manifested... a lack of transparency in the reporting procedures”. This culminated in the company’s failure to communicate to the university about how the SOP HRD Management Authority had declared some of the expenses which the University was expecting from the project were ”ineligible”.

Eventually, SOP HRD allowed the expenses to be paid. However the university did not receive them, and argued that, although Operations Research SRL had cashed the money in February 2014, these funds had not been passed on to the learning institution by May 2016. As a consequence, the university filed for legal action to recover 170,000 RON (39,000 euro, approx.).

Despite the imperfect collaboration between Operations Research SRL and the University of Iaşi, this trend was repeated with another prestigious university in Cluj-Napoca in 2015. The cityaudit.ro brand was again in the equation, but as an association, not as a website. Thus, according to a public announcement on 16 January 2015, CityAudit.ro Association partnered with Cluj’s Babeş-Bolyai University (UBB) on the SOP HRD-financed project ‘Developing Entrepreneurship and Enhanced Professional Skills for Students from the North-West Region’. The 0.5 million euro project aimed to improve curricula by developing entrepreneurship for 250 students and 20 people involved in higher education study programs.

The non-payment story in the University of Iaşi was repeated in Cluj. According to an article by press agency Mediafax in January 2017, CityAudit.ro Association did not pay the amounts it owed.

A student of UBB and former participant in the project, Adrian Suteu, stated to Mediafax that, in 2015, 70 members of UBB’s Faculty of Political, Administrative and Communication Sciences (FSPAC) participated in the project, where they drew up business plans and each expected 2,500 RON (575 euro) for their efforts. ”The problem is we had to receive the money by March 2016, but we have still not received it,” said Suteu. ”Nobody wants to talk to us, it's a total lack of transparency... We have only been told that the money exists, but it’s been held back, but teachers who have been lecturers in the project have been paid.”

At that time the University of Cluj explained that Cityaudit.ro Association was responsible for paying the prizes to the 70 students and had only handed over one third of the cash in 2016. It aimed to pay the difference after clarifying the situation with the Regional Intermediary Body (OIR) of SOP HRD, which monitors EU projects. But at the time, Cityaudit.ro Association and SOP HRD were in litigation.

Another issue that dogged Operations Research was a conflict of interest. CityAudit.ro Association, according to an NGO public registry, was founded in Bucharest by Cătălin Ştefan Stancu - its president. In 2013, Stancu was an associate in public opinion survey company, Sociopol, according to the ‘Official Gazette’, the Romanian state’s official publication of events. Stancu's partner in Sociopol was Mirel Palada. At that time Palada was spokesman for then-Prime Minister Victor Ponta of the Social Democratic Party (PSD), a position he held until the fall of 2014.

However Palada - a public counsel - owned a company with Stancu. In April 2014, Sociopol was awarded European money by the Ponta government for a project targeting the Roma community, ‘TurArt - Equal Opportunities for Work in Tourism and Handicraft for Women in Difficulty’.

This project won 5.8 million RON (approx 1.45 million euro) of SOP HRD funding to promote ”flexicurity” for women who could not attend a 9-to-5 job.

Mirel Palada refused to speak to us on this issue.

Project Five: Another Conflict of Interests?

The Ministry of Labor was responsible for granting EU funds in human resources between 2007 and 2013, so what happens when this Government department gives millions in European money to a company that hires a former Ministerial counselor’s firm for its marketing? Does this indicate a revolving door between winners of EU cash and the Ministry which grants the funds?

We examine the case of Catalactica.

One of the biggest winners in the EU-funded Human Resources Development Program, the Bucharest association Catalactica was profiled on TV station Digi 24 in 2017. ”Sorin Cace is the director of the Catalactica Association and a researcher at the Quality of Life Research Institute,” reported the TV station. ”He claims that in seven years he has run 25 SOP HRD projects in which the EU has invested over 40 million euro.”

What is exceptional is the association’s ability to negotiate the jungle of EU funds. Cace and his wife wrote 64 applications in 2013, and won financing for 32 projects. These were too many for Cace to manage, he said at the time.

Digi 24 revealed that the largest recipient for Cace's association was Teleorman County in south Romania, which is a fiefdom of the current head of the governing Social Democratic Party (PSD), Liviu Dragnea. ”The money run by Sorin Cace turned his association into one of the largest contributors to the county budget,” said the report.

There are several issues with these projects. One priority for the grantee seems to be have been the purchase of a car. According to the Court of Accounts' public report for 2012, the institution states that in Catalatica’s project ‘Resource for Women and Socially Excluded Roma Groups’, a motor vehicle was bought through hire-purchase (leasing) at a cost of 26,000 euro, while renting a car would only have cost only between 7,000 to 18,000 for a year. The report concluded: ”The beneficiary did not demonstrate that leasing was the most cost-effective method for obtaining the use of the asset.”

However, the acquisition of the car by Catalactica is insignificant compared to the total value of the project ‘Resource for Women and Socially Excluded Roma Groups’. This was 16.5 million RON [3.75 million euro], from which only slightly more than 300,000 RON was the beneficiary's contribution, and over 16 million RON came from the EU.

Partners in the project were the Life Quality Research Institute and Bolt International Consulting - L. Katsikaris & Co, a consulting firm based in Greece.

Despite the huge budget of almost four million euro, the project site, integrat.org.ro, which should have helped Roma women access the labor market, is no longer available.

Catalactica Teleorman also won projects called ‘PROACTIVE - from marginal to inclusive’ (approx. 3.75 million euro), ‘DURABIL - from subsistence to sustainability’ (approx. 4.5 million euro) and ‘COME - Staged Manifest Behavior’ (approx. 483,000 euro). These projects have a partner in common: the service provider Scutaru Strategic Consulting SRL. This small consultancy firm in Bucharest received, on paper, a total of 934,000 RON without VAT, equivalent to over 220,000 euro, from the three projects.

In each of these cases, the project administrators - Catalactica - received only one offer for the requested services, from Scutaru. The supplier was practically the only company invited to take European money.

There is another reason that contracts concluded by Catalactica Teleorman with Scutaru Strategic Consulting SRL are interesting.

Until the beginning of 2013, during the period when he entered into contracts with the association, Codrin Scutaru was the only associate and manager of the company. He gave up the firm's shares at the beginning of 2013 not by accident, but because he was appointed state secretary in the Ministry of Labor. It was not the first time that Scutaru occupied a position here. According to his resume, published by gandul.info, Scutaru entered politics as a counselor to PSD Labor Minister Dan Mircea Popescu during the Prime Minister Adrian Năstase government (2000-2004), was also an adviser to Prime Minister Calin Popescu Tariceanu (2004-2008), and later joined the staff of the Liberal Party (PNL) State Secretary of Education, Svetlana Preoteasa, before leaving the public sector to work in private counseling.

Why is Scutaru's connection with the Labor Ministry important? Because, for years, the SOP HRD funds were administered in Romania by the Ministry of Labor. It is possible that Scutaru was well aware of the mechanisms by which European money can be accessed.

But maybe the contracts that Catalactica gave to Scutaru - without an open tender - were just a coincidence. This is hard to believe. According to his CV, between 2010 and 2013, Codrin Scutaru was a researcher of the Quality of Life Research Institute (ICCV). At the same institute was another researcher called Sorin Cace, the chairman of Catalactica. In fact, ICCV has been a partner of Catalactica in many of the successful SOP HRD projects.

So, when Cace signs contracts for SOP HRD money with Scutaru, he pays his own colleague at ICCV. This seems to be an obvious conflict of interests. But when we contact Scutaru with this allegation, he argues: ”The commercial relations between my company and Catalactica were compliant to procedures that were transparent and legitimate. I don't think there was any conflict of interest just because Sorin Cace and I were both researchers at Quality of Life.”

Meanwhile Cace also argues there was ”no conflict of interests” because he was ”not a manager” at that time at Quality of Life, and the two were only researchers together.

Infographics by Studio Interrobang

Opening picture: copyright Petrut Calinescu

Part of a project financed by Journalism Fund