The residents of Ortaköy faced a gruesome choice. When the decision was taken to transform their village into a reservoir to serve the citizens of Istanbul, many were forced to ask themselves if they could bear to leave their dead behind, buried beneath seven hundred billion litres of water from the Melen River, along with the history and hazel trees of a place first settled in the 14th century by Turkmen nomads and tree cutters.

In 2012, Ortaköy’s residents began excavating the remains of generations of deceased and transporting them to the cemetery in the village of Gümüşoluk, “the last village before the dam,” a place the water would never reach.

Two years later, with the bulldozers closing in, they bid a final farewell to Ortaköy. By the time the demolition of Ortaköy was completed, only the mosque and a single, faded green building remained.

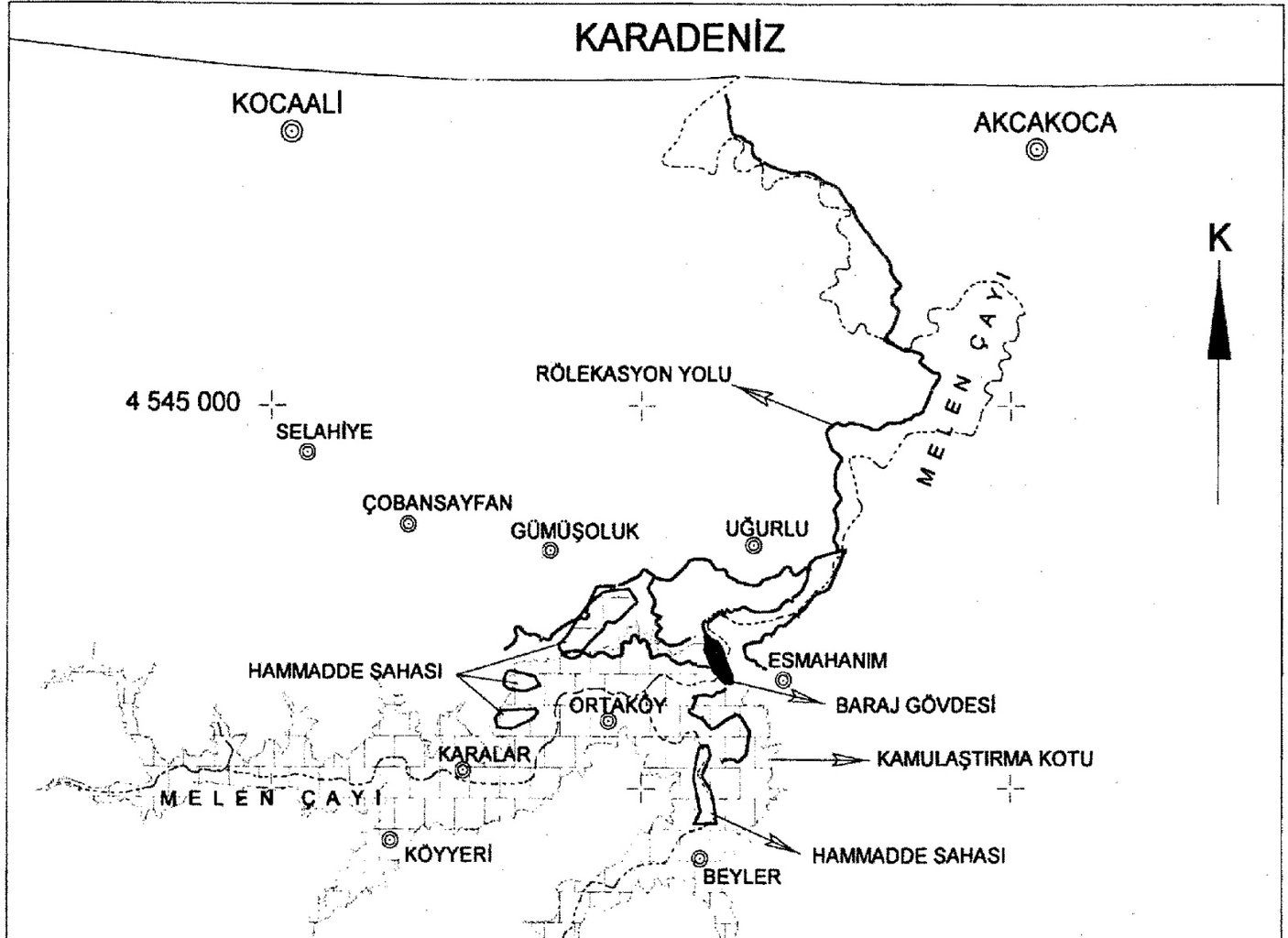

The Greater Melen water supply project is a large-scale infrastructural investment that is expected to bring 1070 million cubic meters of freshwater annually from the Melen River to Istanbul through 189 kilometres of pipelines. The project's last and pivotal part, the Melen Dam, is a promised cure for Istanbul’s chronic water shortage.

But nearly a decade later, the dam that displaced thousands of people stands unfinished, plagued by faults and cracks along its austere concrete wall. The place that was once Ortaköy is not underwater. One can still walk along the main square where the village café once stood. The hazel trees have regrown.

The Black Sea visited Ortaköy to understand the consequences of Istanbul's quest for water and the Greater Melen Project. We talked with experts, former residents of Ortaköy, and sources who worked on the project to explore how the second-biggest dam initiative in Turkey became marred by broken promises, displaced communities, and squandered funds.

It takes a village…

Asuman Bakas, whose family were among those who relocated their deceased relatives.

Asuman Bakas was in her mid-20s when authorities ordered the eviction of the locals, and her family decided to exhume dozens of their relatives. Now living in Karasu, 30 kilometres from Ortaköy, she works at the Chamber of Drivers and Automobiles in Kocaali. During an interview, she told us that the family felt it was their duty to carry out the work themselves, even if she couldn’t bear to witness it personally.

"My brother opened my father's and grandfather's graves,” she said. “He had to move whatever was left of their bones. If you ask me, did I go? No, I didn't. I definitely couldn't put myself in that psychological state. Only my brother and cousins could do it.”

Many of the Ortaköy’s final residents took on this grim task. They had buried their dead once. It seemed only right, a matter of duty, that they did it a second time. “No one else could do it” or “We didn’t trust anyone else,” they kept saying.

In the same building is the office of Zeki Sargın, president of the local Chamber of Drivers and Automobiles. For 50 years, he lived on a 500-acre stretch of his family’s ancestral lands in Ortaköy until the court evicted him. He told us that when he dug up his mother and father, it was like “seeing them die for a second time.”

“May Allah not inflict such pain on anyone,” he said.

In Kocaali, we also met Cemal Angın, the former mayor of Ortaköy, who was elected three times between 1999 and its demise in 2014. He welcomed us with a bowl of hazelnuts, which, for many there, is a symbol of life in the Black Sea region. A nameplate on his desk reads ‘Kocaali Municipality Vice President’. When the court orders were handed down, Angın dug up and relocated those members of his family who died in the 1980s. Mercifully, when his mother and father both died in 2014, they were buried in Gümüşoluk’s cemetery.

“There is a spiritual sadness,” said Angın. The only consolation for what has disappeared, he added, is that 17 million people will benefit from the dam. “It is a comfort to us, albeit a little.”

Angın, Bakas, and Sargın were children when they first heard of the government's plans to construct a dam that would destroy their homes to supply water to Istanbul, 200 kilometres to the west. Their first memories of it stretch back to the 1980s. Back then, it seemed like a tall tale spread by adults, a rumour no one truly believed. In the years before the expropriation, the people of Ortaköy lived in a trance, stuck between disbelief at the prospect of their village's demise and the feeling they were powerless to stop it. The authorities and engineers in their Istanbul offices, meanwhile, were drawing the lines that would determine Ortaköy's underwater fate.

It took almost 30 years between then and the day they eventually left, when the demolition workers began knocking on their doors.

Cemal Angın, the former mayor of Ortaköy.

The Waterless City

How does a village disappear? To understand how the Great Melen Dam project was born, one must look beyond the valleys surrounding the Melen River to the city of Istanbul.

“Istanbul is historically a waterless city,” said Haluk Eyidoğan, former CHP politician and a professor of geophysics and seismology at Istanbul Technical University. Despite its placement astride the iconic and salty Bosphorus Strait, Istanbul is a city with inadequate access to fresh water, meaning it developed an early dependency on resources beyond its borders. As far back as the 4th century and the establishment of Constantinople, successive Roman emperors, like Constantine, Valens, and Theodosius, constructed or expanded a system of aqueducts to transport water from the marshes of the Belgrade Forest or the Istranca mountains. By the mid-sixteenth century, Istanbul began to rely upon several dams.

The city grew over the centuries, and so did its thirst. By 1990, Istanbul's population was 6.6 million, and growing each year. Water supply became a significant problem, and the city lived through a decade of chronic scarcity and recurring droughts.

A researcher from Istanbul shared a distinct memory of this period: a childhood spent in a house where water was stockpiled in pans and buckets in every corner. She describes it as a period of widespread distrust in “the system.”

The anxiety was compounded by a 1993 political corruption probe into the Istanbul Water and Sewerage Administration (İSKİ), under the purview of the Social Democratic Populist Party mayor, Nurettin Sözen, who was embroiled in the İSKİ scandal after director, Ergun Göknel, was charged with embezzling public money. Sözen was eventually acquitted, but the fallout from the İSKİ-Skandal helped elect the then-outsider candidate, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, as mayor of Istanbul, beginning a decades-long career that continues to dominate Turkish politics to this day.

The public administration’s thirst accelerated, and by the turn of the century, İSKİ had expanded the city’s water infrastructure by constructing several dams. When these also proved to be inadequate, Istanbul again looked beyond its borders to the waterways of more distant regions. Engineers at Turkey’s General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (DSİ) began to calculate the potential of the Greater Melen Project.

For Ortaköy, even the rumoured threat of a looming dam was enough to create a culture of purgatory. “People would not invest in the village anymore,” said Angın, the former mayor. Infrastructure, renovations and investment began to dry up in 2000. Locals started buying property elsewhere, children went to school in neighbouring districts, and the bank closed down.

The rise of the Great Melen Dam and the fall of Ortaköy

The 2007-2008 drought in Turkey helped seal Ortaköy’s fate. With taps running dry in Istanbul and Ankara, municipalities were forced to implement water rationing, the state expedited the pipeline water transfers and the Melen Dam.

The DSİ activated the first of four stages of the Melen project, turning on the pumps of the Melen regulator on 20 October 2007, three years earlier than expected. With 268 million cubic meters of water flowing through 235 kilometres of newly constructed pipelines, they turned their attention to phase two: the dam.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report for the dam described this second stage of the Greater Melen Project, expected to be completed in 2014. The project’s numbers were staggering. It is ultimately expected to supply 1,077 billion cubic metres – more than a trillion litres – of water annually to Istanbul, the EIA stated. The Melen Project was to be everything Istanbul hoped for – a concrete solution to a thirsty city.

Exactly how long this would alleviate the city’s water needs remains ambiguous. The EIA report gives two dates. The project, it stated, will meet the “needs of Istanbul until 2040,” when it predicts a population of 17 million, a highly unrealistic figure that is likely to be surpassed in 2025, a decade and a half early. It also gives the date 2070, which, in later official documents, was changed to 2071, probably to coincide with the 1000-year anniversary of the victory of the Seljuk Turks over the Byzantine Empire. The date also refers to the government’s vision of 'the Century of Türkiye'.

The government’s Official Gazette announced the expropriation of lands for the project in 2012. Ortaköy was one of the unlucky villages that found itself on the wrong side of the line.

The announcement of the expropriation of the lands around Ortakõy, from the Official Gazette.

With the machinery grumbling in the distance, Ortaköy’s residents began to dig up and remove their ancestors one by one. By 2014, the last of the town finally left their homes and hazel trees. Ortaköy's mayor, Angın, was among those final few. “The ship's captain is the last to leave,” he said.

Bakas told us that she and one other family remained in the village for around “a month after the water and electricity were cut off.” Using a generator for power, they harvested the hazelnuts from the trees below their home until the presence of the demolition crews and vehicles made staying difficult. “The demolition crew was coming every day,” she told The Black Sea.

“When they came to demolish my house,” Sargın said, “they first started from my mother and father's room. It's not possible to describe the sadness of this in words.”

Problems from the ground up

Ortaköy stood empty, but the Melen project began to suffer delays. Rumours circulated of major problems. Although construction of the dam’s wall was not completed until August 2017, cracks had already started to appear in the body of the structure as early as October 2016.

On 10 February 2022, Haluk Eyidoğan received an unexpected email. “I have read your article,” it began. After taking an interest in the Melen Dam affair, Eyidoğan had recently published a detailed, technical account of the Melen project’s “broken dam.”

The email's author was Hasan Paçal, an insider who worked as a regional manager in DSİ’s Istanbul office between 1996 and 2002 and helped launch the Greater Melen Project. In the correspondence shared with The Black Sea by Eyidoğan, Paçal offered his account of what went wrong. The Black Sea subsequently contacted Paçal and received further clarifications.

Further pages of handwritten notes by a reputed civil engineer at DSİ, reviewed by The Black Sea, support the insider’s account. We consulted an engineer who worked for a company participating in the project to verify its claims. They confirmed the validity of its contents and asked to remain anonymous.

A major issue came from the ground. All the way back in 2009, the EIA report noted the potential risks of the Great Melen Dam project, identifying the presence of low-bearing and alluvial soil. “It’s the weakest soil for ground surveys in geology,” said Eyidoğan.

Because of the soil, the report recommended a concrete face rockfill dam, known as CFRD, which consists of rockfill or gravel compacted into layers and then coated with concrete to ensure impermeability. “They are more flexible than rigid concrete dams,” Eyidoğan said. Both he and Paçal both agreed that a CFRD dam is more appropriate for Ortaköy’s soil. It is also “the most earthquake-resistant dam,” Paçal wrote, a doubtless benefit in a region at risk of a major seismic event in the coming years.

The Melen dam, however, is not a CFRD.

Sometime after the EIA report, the dam was changed to a Roller-Compacted Concrete (RCC) type. “What happened? We don’t know,” said Eyidoğan. From an engineering point of view, the difference between the two is substantial: RCC dams are cheaper and faster to build but are much heavier. The engineers would certainly have to conduct geological mapping and strengthen the land on which the Melen dam is constructed.

Based on the engineer’s handwritten notes, the dam change was largely motivated by a drive to reduce the construction time by between two and four years.

The change necessitated more preparation work. The RCC dam required the engineers to inject concrete and chemicals into the soil to allow it to handle the heavier load. After this process, however, it appears that DSİ failed to properly carry out the necessary controls and testing of the soil conditions.

“In the project, sufficient drilling, geological and geophysical studies, and ground mechanics studies (especially 3-axis tensile tests) were not carried out. They were content with 3-5 drillings. It’s unbelievable,” Hasan Paçal wrote. Paçal told The Black Sea that the project would have required 20-25 drillings at a depth of 35 m under the body and at least 10 drillings at a depth of 25 m on the slopes.

In 2017, DSİ hired consultant engineers to investigate the causes of the cracks in the dam, as reported in 2020 by a parliamentary research group for the Republican People's Party. The consultants submitted a report that criticised the preparation work of the project and warned that the “drilling and ground safety inspections required for this type of ground were not carried out adequately.” Paçal confirmed this, writing that “the ground studies that needed to be done for the dam were partially insufficient or were not done at all”.

Several sources, including Paçal, believe that the decision to build an RCC dam and the insufficient ground surveys caused the cracks and structural problems—and, ultimately, the project’s ten-year delay. Hasan Paçal said the tender was always for an RCC, meaning it was the DSİ’s decision to change the dam.

Ever since the cracks appeared, the DSİ has tried to repair and strengthen the dam body, none of which have permanently fixed the problem. Paçal wrote: “The dam cannot be repaired. Building an RCC dam requires serious experience and quality control. It is a dam type that is not suitable for the ground structure, that is, its settlement sensitivity is very high. Controlling shrinkage requires serious experience and knowledge. These have always been neglected in the Melen Dam”.

As a seismologist, Eyidoğan was deeply concerned that the EIA report did not properly analyse the earthquake risk, a glaring omission for a site in a first-degree earthquake area because of the North Anatolian Fault Zone, the very same fault that caused the 1999 Marmara earthquake that killed 17,000 people.

Paçal agreed: “Thank god the body did not explode when it was full of water, a great disaster would have occurred. I hope I can write you the real story later.”

The Black Sea emailed a list of questions to the DSİ. We did not receive a reply.

The village of the dammed

Two men fish near the base of the Melen Dam.

More than ten years have passed since the last of Ortaköy's inhabitants left. The hope that the town would simply be reborn elsewhere faded as families dispersed to towns like Düzce, Karasu and Caferiye, close to the Black Sea, where the Melen River flows to the sea.

Zeki Sargın is happy at funerals. “Can you imagine people being happy at a funeral?” he asked. For him, funerals are occasions to gather with their neighbours, friends, and relatives. Since the expropriation, there have been fewer of them —another reminder of what is lost.

“Right now, there are those doing very good economically and those doing very bad,” he said. If the village were still there, those in need would have people to turn to. “We used to help each other,” Sargın said.

Asuman Bakas told The Black Sea that after the evictions, most of her family relocated to nearby Karasu. Her elderly mother, who had lived in Ortaköy for around 60 years, moved into an apartment but, a decade later, still struggles to adjust and find purpose. She asks Asuman, "Are we going to stay here forever?" or asks when she will be allowed to return home.

During summer, Asuman and her family visit their old village to harvest the hazelnuts. Being in the orchards and breathing fresh air provides comfort to her mother. “She has had a lot of trouble since she left the village,” she said. “When we go to the village to pick hazelnuts, she has no trouble at all. Whenever we return to Karasu, we [have to] go to the doctor every two days.”

We visited Ortaköy and walked its dirt paths to where the main square once stood, now reclaimed by vegetation, among them the hazels. There are small signs of life. A few makeshift sheds have sprung up, occupied by former Ortakoy residents who return, like Asuman’s family, to harvest the hazelnuts.

One old couple arriving in a car told us that they visit occasionally to harvest the hazelnuts and tend to a vegetable garden. They asked not to be identified: “We shouldn’t be here,” they said. They wave goodbye and drive away.

A few kilometres from the abandoned plot of land that was once Ortaköy, along a winding road and an unnamed stream, past remnants of other lost villages, stands the Melen Dam, unactivated and massive, a concrete monument to the greater needs of Istanbul, a place more important than the likes of Ortaköy.

Additional reporting support: Kerem Yalçıner

Photographs: Bradley Secker

Editors: Craig Shaw, Himanshu Ojha, Mina Eroğlu, Cemre Demircioğlu

Supported by JournalismFund Europe and Arena for Journalism in Europe