Ukraine oligarch links to off-shore cash haven revealed

It began with a messy divorce.

Maria Firtash, born Kalinovskaya, the ex-wife of Ukrainian oligarch Dmitri Firtash, felt cheated from the terms of their split - a settlement which landed her with only 36 million USD.

In 2007 she secured the services of a top consultant to pursue her share of her ex-husband’s assets, possibly worth in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

According to documents obtained by the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), she hired UK-based fraud-buster Martin Kenny to chase after the funds.

Kenny filed an order in June 2007 that forced Commonwealth Trust Limited (CTL), a register agent in the British Virgin Islands (BVI), to disclose information on their clients’ firms, so he could see whether they were linked to Firtash.

Business owners used agents such as CTL to register their companies in the BVI, as this allowed ownership of these firms to be anonymous. This model can help such owners launder money and avoid tax.

Neither Firtash nor Kalinovskaya responded to requests for comment for this article.

Issued on 8 June 2007, the order stated that the Ukrainian billionaire hid assets from his ex-wife and set up at least two businesses through CTL, a register agent in the BVI.

BVI regulators - the Financial Services Commission - found that CTL violated the islands’ money laundering laws and banned it from taking on new clients, according to internal company documents, leaked to ICIJ.

A High Court judge in the BVI said Maria Kalinovskaya was seeking to preserve her presumptive 50 per cent interest in the “very substantial assets” of the marriage that were “fraudulently concealed” by Firtash through “various entities” in different locations.

The decision to allow Kalinovskaya’s lawyers to go hunting for Firtash’s assets was unprecedented for offshore jurisdictions.

Due to leaked emails, we can reveal how this order shocked BVI registration officials, who feared it could break down the entire system of off-shore payments to the tropical archipelago.

Tax paradise, global loss

The vast flow of offshore money — legal and illegal, personal and corporate — can roil economies and pit nations against each other.

Europe’s continuing financial crisis has been fueled by a Greek fiscal disaster exacerbated by offshore tax cheating and a banking meltdown in the tax haven of Cyprus, where local banks’ assets have been inflated by waves of cash from Russia.

Anti-corruption campaigners argue that offshore secrecy undermines law and order and forces the average person on the street to pay higher taxes to make up for revenues that vanish overseas. Studies have estimated that cross-border flows of global proceeds of financial crimes total between one trillion USD and 1.6 trillion USD a year.

ICIJ’s 15-month investigation found that, alongside perfectly legal transactions, the secrecy and lax oversight offered by the offshore world allows fraud, tax dodging and political corruption to thrive.

Ukraine is a major victim of capital flight and is a relatively huge recipient of money from offshore jurisdictions.

According to a 2012 report by US-based think tank Tax Justice Network, Ukraine ranked 15th worldwide on a list of capital flight source countries.

The report added that Ukraine has contributed some 166.8 billion USD to the global offshore industry. As the top foreign investor into Ukraine, offshore Cyprus has put 17.6 billion USD - almost one third of all FDI inflows - into the country. Furthermore, such offshore jurisdictions as the British Virgin Islands and Belize have invested heavily into Ukraine – with 2.2 billion USD and one billion USD, respectively.

Much of this is suspected to be repatriated money.

By comparison, US investment in Ukraine since independence in 1991 has been 880 million USD.

This use of offshore havens by Ukrainian businessmen has massively distorted the nation’s economy which, despite its size and assets, has a GDP per capita below Bosnia-Herzegovina, Namibia and Algeria.

"Beginning of the end" for BVI

According to leaked emails from 2007, Scott Wilson, the co-owner of CTL, was terrified when Maria Kalinovskaya obtained the order to force his company to disclose information.

His correspondences refer to fears of a ‘fishing expedition’, which in legalese means giving the lawyers access to find information outside of the scope of the initial case.

Wilson stated: “I’m not even sure what [the order] means (and if it means all records, I’m not even sure how we could comply), so if it means what it seems to mean, this is unprecedented. This would be a fishing expedition of the most extreme definition. Not only would compliance with such an order be the end of us, it would be the beginning of the end for BVI.”

Wilson concluded his e-mail message: “Frankly, I wouldn’t expect something like this to fly even in New York and I am astonished that the judge is not tossing these guys out of his BVI courtroom.”

Thomas Ward, his partner, thought that “this is an amazing order. One wonders what the judge was thinking. I agree that this would be the end of us and the BVI – was this order issued by a BVI court? Boggles the mind!!”

Ward quickly grasped the gravity of implications if the order was to be followed: “As Scott says, this would seem to mean the end of effective confidentiality on the BVI if a fishing expedition of such unbelievably broad scope is permitted… I agree that we must defend this aggressively and to the full extent possible.”

Pushback was swift in coming. CTL sought to use the courts to delay and frustrate the order.

One scare tactic used by CTL against Kalinovskaya and her lawyers was to claim a huge legal bill of more than 200,000 USD. At the beginning of the court trial, a CTL lawyer asked the judge to order Firtash’s ex-wife to immediately pay 58,675 USD to cover the offshore register’s legal costs so far and put up security for another 175,000 USD to cover its legal and paperwork costs going forward.

Email communications show the real legal costs were about 5,000 USD and Firtash’s personal lawyer Colin Mason even filed a complaint in the local court against the inflated costs asked by CTL.

The order to access the information was eventually quashed on 18 July 2007, but not before Mason got involved, flying to the British Virgin Islands to take part in the court hearings.

The domain part of Mason’s e-mail address – Scythian.co.uk – is the company, Scythian, that was paying tens of thousands of dollars in donations to British Conservative Party MP Pauline Neville-Jones through Robert Shetler-Jones of one of Firtash’s companies Group DF, according to newspaper The Guardian.

Partners in Business and Pleasure

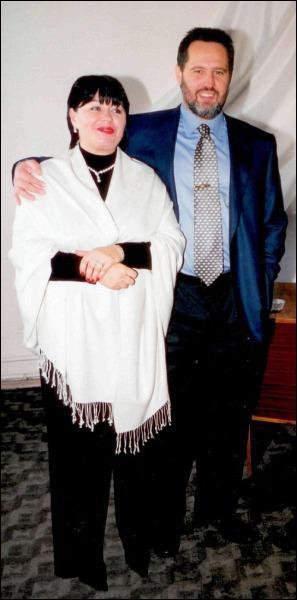

Kalinovskaya and Firtash were married between 2002 and 2005. In interviews and according to a 2007 investigation conducted by the newspaper Ukrainska Pravda, she helped Firtash start his business. They worked together in the early 1990s in Ukraine, Russia and Germany.

She initially got a divorce settlement of 36 million USD, but felt cheated after learning her ex-husband was worth more. In 2006, the Ukrainian news magazine Korrespondent estimated Firtash’s assets at 1.4 billion USD.

That same year Firtash set up Group DF (after his initials), months after he publicly admitted owning a big stake in RosUkrEnergo, a monopoly gas supplier to Ukraine partnered with Russian gas giant Gazprom.

Group DF Limited became the holding company for Firtash’s vast interests in energy, chemicals and real estate.

Firtash has expanded his chemicals empire in Ukraine since President Viktor Yanukovych took office in February 2010.

In recent years he ventured into philanthropic projects, notably funding the Cambridge Ukrainian Studies department in England and revamping the campus of the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv.

Today Firtash, 48, is worth an estimated 3.2 billion USD, according to Korrespondent’s latest assessment conducted with Kyiv-based investment bank Dragon Capital.

Offshore Labyrinth

Over the last decade Firtash has extensively used Common Law offshore jurisdictions to register his wide network of companies.

His maze of offshore holdings was so complex, it seems the billionaire himself was at times confused about their status.

In early 2009, one of his associates sold his Hungarian firm EMFESZ, a serious gas player, for one dollar to an unknown company from Switzerland, RosGas.

This deal was administered by Istvan Goczi, a director at the CTL-registered Group DF, who sold EMFESZ’s Cyprus-based parent company Mabofi.

Firtash did not seem happy about this deal.

He terminated his working arrangement with Goczi, but had to go to court to regain control over EMFESZ in February 2013.

Documents leaked to ICIJ also show that CTL was sitting on a treasure trove of information related to Firtash and entities related to Kyiv-born crime lord Semion Mogilevich, who earlier topped the US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s most wanted list. Some of the entities owned luxury properties, such as the Three Musketeers Castle in France.

The data revealed that CTL had earlier handled company registrations for Group DF and DF Investments, both belonging to Firtash, through Cypriot law firm Demetriades Shakos Pifanis.

The person handling all incorporations was a senior partner at the law firm, Andreas Pifanis.

Pifanis didn’t respond to a request to provide comment for this article.

Altogether ICIJ found that Pifanis had registered some 140 companies with CTL starting in 2005 and ending in 2009, in most of the cases using Annex Holdings as a director. Some of these companies were or are officially part of Firtash’s group and some are unknown to the public.

Annex Holdings made headlines in 2005 when it paid a Washington D.C. lobbying firm to represent the interests of then-Ukrainian Energy Minister Yuri Boyko, a close associate of Firtash.

According to US diplomatic cables, Boyko had helped set up Swiss-registered RosUkrEnergo and sat on one of its boards. He also wielded power-of-attorney control over Firtash’s assets in the past.

An ICIJ investigation based on leaked documents also found that among the companies registered by CTL, two are linked to Mogilevich: Highrock Properties established in 2000, but which was later re-named Kemnasta Investments Ltd under lawyer Pifanis’ supervision, and Barlow Investing Ltd, registered on behalf of Galina Telesh, former wife of Mogilevich.

Highrock Holding, a similarly named vehicle, was used both by Firtash and Mogilevich’s associates or their former wives, according to the Financial Times.

US State Department cables posted on WikiLeaks website have reported that Firtash acknowledged to a top American diplomat “that he needed, and received, permission from Mogilevich when he established various businesses, but he denied any close relationship to him.”

Internal CTL company documents also showed that it had set up Lacoste de Pratviel Ltd in 2006, a winery that is part of a famous castle – Chateau d’Arricau-Bordes – worth more than three million Euro. The castle was listed as the property of Shetler-Jones in 2010, a supervisory board member at Group DF and its CEO from 2007 to August 2012.

In a letter to the owner of CTL, Pifanis describes the nature of his business: “As I explained to you during our meeting we are involved in serious money transactions through the use of BVI companies.”

In a later email he explains that Firtash is one of his biggest clients: “this Group is one of the largest Groups we administer, who have already bought from us few dozens of BVI companies that we bought from you.”

Pifanis furthermore appears keen to please Firtash and becomes agitated when things drag at CTL.

One of CTL employee’s, Shonia Matthew, alleged to a colleague in a 7 December 2006 email that she was threatened by Pifanis: “he once threatened he will kill me if he comes to BVI and since then I am handling his requests professionally and without delay… but at the same time no extra ‘sweetness’.”

Multinational money-laundering exposed

Documents used to report on this story come from a cache of 2.5 million files, which cracked open the secrets of more than 120,000 offshore companies and trusts, exposing hidden dealings of politicians, con men and the mega-rich the world over.

The secret records obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists lay bare the names behind covert companies and private trusts in the British Virgin Islands, the Cook Islands and other offshore hideaways.

These secret files show CTL had served as a middleman for an extensive list of shady operators around the world, including in Russia and the US – setting up offshore companies for securities swindlers, Ponzi fraudsters and individuals linked to political corruption, arms trafficking and organized crime.

There’s no evidence CTL engaged in fraud or other crimes. Records obtained by ICIJ indicate, however, that CTL often failed to check who its real clients were and what they were up to – a process that anti-money-laundering experts say is vital to preventing fraud and other illicit activities in the offshore world.

The documents show authorities in the British Virgin Islands failed for years to take aggressive action against CTL, even after they concluded the firm was violating the islands’ anti-money laundering laws.

CTL co-founder Thomas Ward blames many of the firm’s problems on “the law of large numbers.” Anytime you form thousands of companies for thousands of people, he said, a few of them may be up to no good.

In a written response to questions from ICIJ, Ward said CTL chose its clients carefully and that it had no more problems than other offshore services firms of similar size.

“I regard myself as an ethical person. I don’t think I intentionally did anything wrong,” said Ward, who has worked as a consultant for the firm since selling it to new owners in 2009, in a telephone interview. “I certainly didn’t aid and abet anybody doing anything illegal.”

It was not until February 2008 – nearly five years after regulators first found CTL in violation of anti-money-laundering rules – that BVI’s Financial Services Commission took action that threatened to put the company out of business. They banned CTL from taking on new clients until it complied with anti-money-laundering regulations.

CTL was reinstated by regulators after it was bought out by a Dutch company, Equity Trust, in 2009, thus getting the ban on signing new clients lifted.

A version of this article appeared in the Kyiv Post in June 2013

Follow us