Turkish Airlines is the pride of Turkey. It has been the country’s flag carrier for nearly one hundred years and is considered among the world’s top airlines. It boasts of flying to around 320 destinations – “more countries than any other airline” – while promising to “widen your world.” All of this exploration is not without an environmental cost. Last year, the airline saw its annual greenhouse gas emissions rise to a record 22.98 million tonnes – around 35% higher than in 2018.

With the climate crisis worsening and pledges to keep global temperature rises to within 1.5C by the end of this decade all but certain to fail, polluting industries like airlines are championing their green credentials. Popular among them is carbon offsetting. They come up with fancy names like KLM’s CO₂Zero (“Be a hero, fly CO2 zero"), British Airways’ Planet and IAG’s Flightpath Net Zero.

Carbon offsets are based on the premise that whatever emissions are generated by your flight can be “offset” by reducing or eliminating them elsewhere. If, say, cattle grazing land in Argentina is converted to a forest of healthy native trees, organisations like the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS or Verra) and the Gold Standard assess the positive carbon impact and issue carbon credits to be traded on the Voluntary Carbon Market.

Turkish Airlines launched CO2mission in 2022, in collaboration with Semtrio Sustainability, a Turkish consultancy service and broker of offset projects, to tackle what it calls its “unavoidable emissions.”

The airline said this would provide a “carbon offset opportunity” to its 70+ million passengers “to neutralise their emissions from their flights.”

And neutralise they didn’t. In the first year of the programme, customers voluntarily donated enough to CO2mission to offset just 1,500 tonnes of its carbon emissions – 0.0065% of the company’s total.

Even this figure is not without complications. While carbon offsets may seem like a handy way for businesses to take responsibility and contribute to a cleaner planet, the system has come under significant criticism. Scientists and environmental activists complain that ventures are opaque and of questionable benefit, allowing polluters to engage in greenwashing while providing free cash to for-profit enterprises. But carbon offsets are big business. Billions have been spent financing eco-projects to permit companies to continue polluting instead of focusing on reducing their own emissions.

Studies and analyses have concluded that most carbon reduction programs are “likely junk” – meaning they are worthless and, in some cases, potentially even generate additional pollution. In recent years, airlines have been subject to several international lawsuits to challenge their advertised claims that flying can be ‘carbon neutral’.

The Black Sea dug into CO2mission projects chosen by Turkish Airlines. There are six in total: three in Turkey, two in the Amazon and Uruguay, and one in Eritrea.

How effective are they? Can Turkish Airlines passengers “fly more environmentally friendly and contribute to a better life in the world”?

Let’s take a look.

Renewables: Credit where credit isn’t due?

Generally, for a project to have genuine emissions reductions, experts agree that it must be permanent, additional, beneficial to the community, and avoid “leakage,” i.e. transposing the emissions elsewhere.

In the case of clean energy, the obvious pitfall is additionality. Bastien Bonnet-Cantalloube, an expert on Decarbonisation of Aviation and Shipping at Carbon Market Watch, a non-profit independent watchdog, said that “renewable energy projects have become so economically viable that they do not require carbon markets to exist. This means that they do not provide additionality, except perhaps in countries where the transition to renewable energy is not as feasible as in others.”

There are three projects in Turkey: the Bares II Wind Farm, Gezin Solar Panels and the Büyükdüz hydropower dam.

Each is a longstanding renewable energy scheme that appears to violate the principle of “additionality” for carbon offset credits. Simply put, if the credits were taken away, these projects would likely still occur and avoid the same emissions.

Professor Barbara Haya, director at Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, told The Black Sea: “What we do know about the hydropower and wind power projects generally around the world is that there's a lot of non-additional crediting, and the program is not able to filter out the non-additional projects.”

The Büyükdüz hydropower plant has been up and running since 2012 in the town of Kürtün in the Black Sea region of Turkey. The region harbours approximately 250 active hydropower plants that necessitated the clearing of forest land, disrupting the ecology and robbing locals of their livelihoods. Haya said, “Large hydropower projects commonly can have devastating impacts on water ecosystems and the waterways. So, the offset program could be subsidising projects with real [negative] ecological impacts. If they're clearing forests, hopefully, that's accounted for in the project design.”

Similarly, the Gezin Solar Panels in the eastern province of Elazığ stretch the bounds of additionality. The project includes installing and operating solar panels, with an estimated net electricity generation of 6393 MWh per year, avoiding 3,952 tonnes of CO2 emissions annually. The companies behind these renewable projects have other businesses, suggesting that they would have gone ahead without the carbon credits. Bilgin Enerji and Ayen Enerji, responsible for the Bandırma wind farms and Büyükdüz hydropower dam, own several wind and hydropower facilities.

“If the companies implementing these offset projects are also building other power plants without offsets, that calls into question the additionality of the projects that they're registering,” Professor Haya stated. “There's a good chance that these would have gone ahead anyway. And these seem really similar, [so] companies that are getting credits for the types of projects that are their core business.”

The Bares II Wind Farm is a host of wind turbines in the Sea of Marmara, off the northwestern coast of Turkey, near the town of Bandırma. It has the capacity to provide enough energy to power 72,000 homes daily.

It’s owned by Enerjisa, a joint venture between massive German conglomerate E.ON, and Turkish billionaire-owned Sabanci Holding, which constructed the €230-million predecessor project, the Bares Windfarm, using €160 million in business loans, half of which came from the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), in 2011. Enerjisa was undoubtedly required to present a strong business case to secure the hefty loans.

“Usually, selling credits makes very little difference to [renewable energy] plants' profitability, because they generate much more revenues from selling electricity,” said Bastien Bonnet-Cantalloube. So either they are viable from selling electricity, and then they don't need credits, or they are not, and then it's unlikely that credits can make a difference to that profitability. In both cases, selling credits doesn't lead to the project taking place.

Companies’ affiliations with fossil fuel and carbon-intensive sectors also raise questions about reliability. Enerjisa, for example, also operates a coal mine and power plant in Turkey and Bilgin Enerji runs a natural gas-powered plant in the north of the country and is the largest shareholder in Jersey-based Genel Energy, an oil and natural gas exploration and production firm with operations in Iraqi Kurdistan, Somaliland, and Morocco.

Ayen Enerji, owner of the Büyükdüz dam, holds 76% of Araklı Energy, which made millions last year from natural gas.

The company behind the Gezin solar panels, Fartaş, is a for-profit solar company that operates a cattle breeding farm responsible for large amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas nearly 85 times more potent in warming the atmosphere than carbon dioxide.

Haya said the system is not effective at filtering out these non-additional projects. It could be that the carbon offset cash is “only making the company wealthier,” she said. “And if the company is also building natural gas plants or coal plants, you could be subsidising those.”

Gezin Solar Panels in Elazığ

Can't see the wood for the trees

CO2mission extends beyond Turkey’s borders to international projects in countries like Uruguay, Eritrea, and Brazil. One of the most notable is Maísa REDD+, part of the UN-designed initiative aimed at addressing deforestation and associated emissions. Despite its official UN backing, REDD+ has been surrounded by controversy since its inception, and the Maísa project in Brazil, specifically, has been embroiled in scandal.

In June last year, Brazil’s labour ministry identified 16 workers who were subjected to slave-like conditions while clearing nearly 500 hectares of forest in the Maisa project area to make way for a cattle ranch – the same industrial activity that the financial incentives were designed to protect against.

Verra, the organisation behind the verification of the carbon credits, told Repórter Brasil that it had terminated the project and that no new credits had been issued since 2020 as a result of non-compliance on the part of the Brazilian landowners.

The credits have been "functionally inactive as a source of climate or sustainability credits since 2022," they said in a statement. Any credits purchased since then could only be “vintages/old harvests,” certified back in 2019.

Turkish Airlines and Semtrio started collaborating on the Maise REDD+ in 2022, meaning their credits are likely older, cheaper and from a project with existing problems.

Professor Yusuf Serengil, a specialist in forest management and ecology at İstanbul University, said that while well-designed and monitored REDD+ projects can play a crucial role in global climate mitigation efforts, the industry can overstate the benefits.

“The Maisa REDD+ project focused on areas in the Brazilian Amazon that are under severe threat of deforestation,” Serengil said, adding that “the project, along with other similar initiatives, did not accurately account for existing conservation efforts by the Brazilian government and other programs, which led to exaggerated claims of reduced deforestation and inflated carbon credits.”

A study of the overstated carbon emission reductions in Amazon projects estimates that nearly 40% of the 50,000 tradable carbon credits issued by the Maisa project until 2017 may not have been genuinely additional.

“Why did Turkish Airlines invest in carbon credits for a conservation project in Brazil that has been discussed for additionality, leakage, and reliability?” Serengil said. “Do they not have experts to check the projects, or were the project credits very cheap to purchase?”

The other forestry initiative in which Turkish Airlines opted to invest its customers’ money is Guanaré in Uruguay, which aims to convert overgrazed grasslands. The project documents show, however, that the primary objective of the Guanaré Forest Plantation Project is “timber production,” which involves mass planting and then cutting down non-native eucalyptus trees for the global paper industry.

The trees, native to Australia, can have a negative ecological impact on the land and augment the risk of wildfires. “Eucalyptus trees can pose a threat to biodiversity as well, due to its overuse of water. It can lead to problems with underground water. While it captures carbon, it can bring along negative impacts on the environment,” Serengil explained. “In case of a wildfire, all the carbon sequestered through the project will literally go up in smoke.”

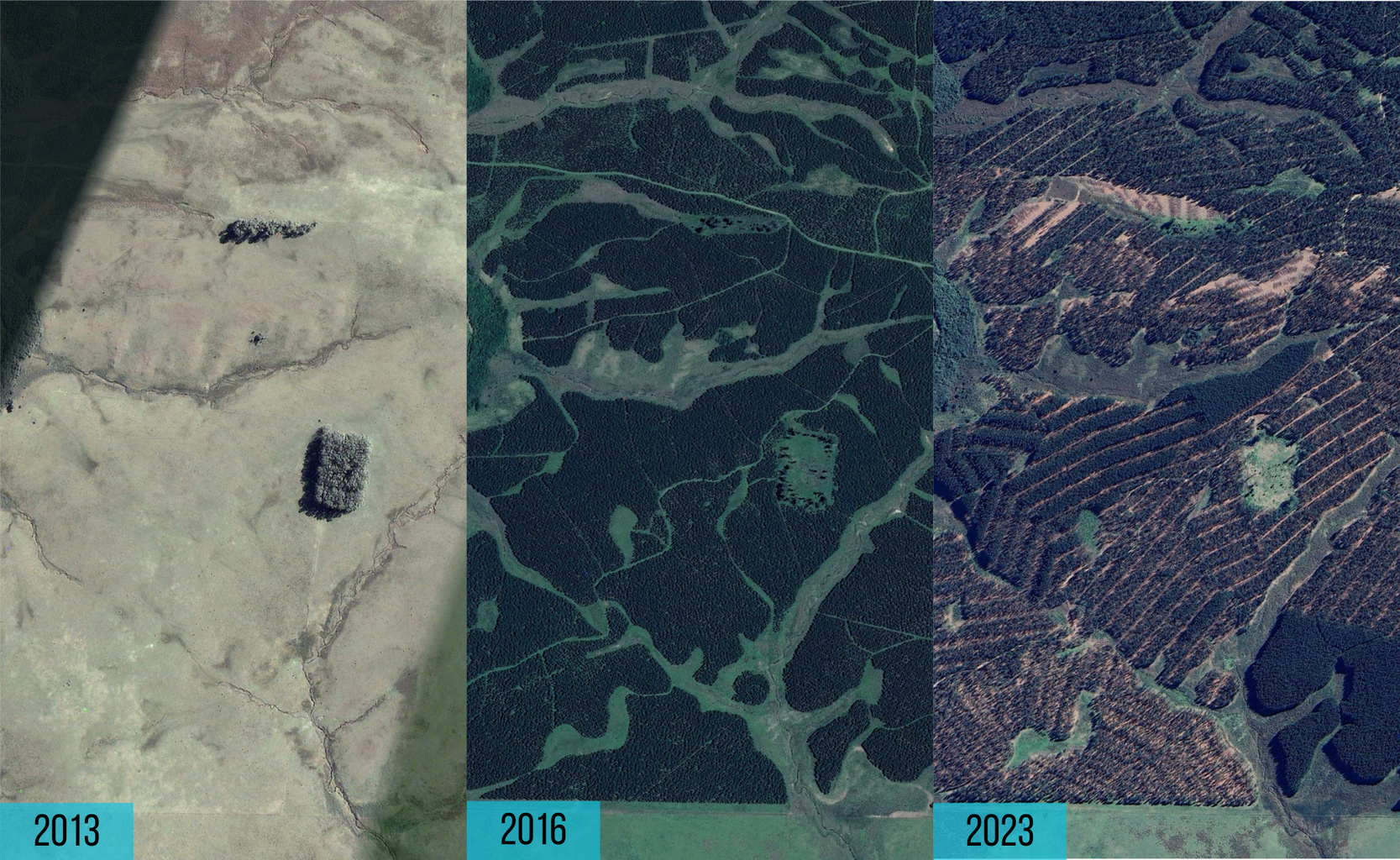

Over time, the species gradually captures less carbon. After 20 years, they will need to be replaced with newly planted ones, leading to significant amounts of carbon leaking into the atmosphere. Satellite images show that part of the forest is already disappearing and will be cleared completely when the project ends, leaving barren land.

“In my opinion, Verra’s verification of an eucalyptus plantation here is not a rightful approach,” Serengil said. “Agroforestry projects, in which agricultural activities take place among trees that absorb carbon, align far better with the ecosystem.”

Guanaré Forest Plantation Project, in 2023. The trees are being cut down for the paper industry. (Source/Google Earth)

"Overcredited by nine times!"

The final Turkish Airlines investment is the Improved Kitchen Regimes Project in Eritrea, a one-man dictatorship in the Horn of Africa. It is designed to lower emissions by providing 8,000 homes in the Anseba district with improved, more fuel-efficient stoves. The plan is to reduce pollution by 95%, saving 24,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year while improving the health of families who would normally be exposed to toxic smoke.

Reports of similar cookstove projects cast doubt on the impact of such schemes. In the rural Koppal district of India, only 60% of homes fully implemented the new devices –the rest continued to cook with wood-burning stoves. One study indicated that the project “did not significantly reduce fuelwood consumption compared to traditional stoves.”

“This is likely to be a good project that does help people and reduce firewood use,” said Professor Barbara Haya, who conducted extensive research on cookstove projects. “My understanding of cookstove projects is that, unlike the renewable and forest projects, a lot of them really need the carbon income to go forward.” But added that “On average, these projects are overcredited by nine times!”

Turkish Airlines and Semtrio did not respond to The Black Sea’s questions or a request for an interview about CO2mission. While its chosen projects are of dubious environmental value, there is nothing unique in the design, mirroring as they do the standard practice for corporations making bold claims about carbon offsetting.

Doğanay Tolunay, professor of soil science and ecology at İstanbul University, noted that organisations that genuinely desire to offset their emissions have limited options beyond those offered by the likes of VCM.

“Almost all airlines, all companies seeking to voluntarily offset their emissions, take the same path,” Tolunay said. “It’s the [Voluntary Carbon Market] system that is flawed. What Turkish Airlines does, just like all other companies, is to use this system for benefit.”

According to Professor Murat Türkeş, an executive board member at the Boğaziçi University Centre for Climate Change and Policy Studies, it is the lack of scientific expertise on the part of companies like Turkish Airlines and its partner Semtrio that leads to investment in “junk.”

Türkeş said that even creditable projects are of limited use in combating climate change. “Offsetting your emissions means that you still emit greenhouse gases; you just balance them out by taking the same amount of carbon out of the atmosphere,” he said. “If we want to really combat climate change, what we should do is to mitigate rather than rely on offsets.”

Tanyeli Sabuncu, the climate and energy program manager at World Wide Fund Turkey, echoes this sentiment. He told The Black Sea that the organisation does not support the use of carbon credits. “Our fundamental principle is that companies should prioritise reducing emissions from their own value chains,” he said. “Offsetting can only be used to compensate for the remainder of emissions (those that cannot be avoided in any way) on the way to the net zero target.”

As Haya pointed out, “There's a real crisis of quality on the market and a lot of greenwashing happening. A lot of credits don't even represent any emissions reductions at all.”

“In a nutshell,” said Bonnet-Cantalloube, “none of those projects...will make up for the huge climate impacts that operating flights – like Turkish Airlines does today – has on our planet.”