Torture of suspects reveals dark heart of Transnistrian justice

Dawn. Early Spring 2011. A forest in a small valley outside Tiraspol, capital of Moldova’s unrecognized Republic of Transnistria.

Along a dirt path, an interrogator and three guards are marshalling Moldovan businessman, Vitalie Eriomenco, who is suffering from multiple head wounds due to hours of torture.

They stop in a clearing between the trees, where the interrogator throws a shovel at the 43 year-old prisoner’s feet and tells him to start digging.

“You will die in the next few minutes,” he tells Vitalie. “If you want to be buried in this forest, you should start digging now. Otherwise, we will throw you in the river - where the crabs will eat you.”

The guards remove his handcuffs. Vitalie thrusts the shovel into the wet earth.

“Nobody will save you,” says the interrogator. “You’re not in Moldova now.”

When he finishes digging to the depth of a grave, he throws down the tool, closes his eyes and waits. The guards raise their guns, aim and shoot.

The bullets fall no further than the ground near the prisoner’s feet.

The four men laugh, strap the hand-cuffs back around Vitalie’s wrists and take him back to his cell.

This fake execution - recounted to me by the victim’s sister Ala Gherman - aimed to force Vitalie to confess to the theft of more than half a million dollars from his own Transnistrian-based business.

His captors wanted him to sign a document admitting the crime and giving away his share to his Transnistrian business associate Victor Petriman.

When the interrogator saw that this tactic failed to force Vitalie to put his signature to a fabricated confession, he telephoned Vitalie’s 17 year old-son, who also lived in the unrecognized Republic.

“We will immediately arrest your son for possession of drugs if you don’t sign the paper,” threatened one guard. “That means 15 years of prison [for the boy]. He is a young boy, he has a nice body - [in prison] some men will love him.”

Vitalie felt he had no choice but to sign.

Everyday torture

At the end of November, Moldova is expected to sign an association agreement with the EU in Vilnius, Lithuania, which will bring the former Soviet Republic closer to integration with the EU.

But this political move will not resolve Moldova's failure to tame its frozen conflict with Transnistia, where mafia-style persecution and torture of prisoners are ongoing.

On paper, the Constitution of the Republic of Transnistria - a nation unrecognized by any United Nations member - reads like the humane legal foundation of any other European state.

It details that no one can be subject to “torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment.”

However in the so-called Republic’s detention centres, our investigations reveal physical and mental torture are common practice.

Ex-cons tell us of the brutal treatment of prisoners. Guards kick detainees and use blunt objects or rubber bats to give blows to the kidneys. Convicts also face solitary confinement without food or water.

If these physical forms of torture fail to yield results for the authorities, they resort to creative methods of abuse, such as threatening the victims with arresting their relatives.

Family strike

Vitalie’s ordeal started on the morning of 29 March 2011, when six men in plain clothes, members of Transnistria’s Department for Combating Organized Crime and Corruption (DCOCC), came to his office and arrested him without a warrant.

At 10:00 PM, eight men - plain-clothes police officers - dragged the handcuffed Vitalie to his house to perform a search, shocking his wife and two sons.

Without a warrant, the police scoured the home for evidence for two hours.

At midnight, they forced Vitalie’s wife and two sons to leave the house, without any change of clothes or personal effects. They sheltered with friends, and later Vitalie’s wife and baby son moved to Chisinau.

The authorities prevented Vitalie from meeting a lawyer. After two days of detention, his interrogator forced him to sign a document renouncing his legal counsel and stating that he would represent himself before court.

On the third day, the authorities provided him with a lawyer of their choosing, while his family hired another from Moldova.

However, the family and lawyers had no access to the details of the case.

Vitalie was a prosperous businessman. From a small town - Vadu lui Voda - on the other side of the River Nistru which borders the two territories of Moldova, he moved to Transnistria in 2002 to set up his first enterprise.

In 2011, by the day of his arrest, there were more than 400 people working for his four companies in the town of Slobozia. This included bread and beer production factories, a mineral water bottle filling factory and a mill.

After the arrest, the authorities told him that his business partner Victor Petriman complained to the DCOCC, accusing Eriomenco of stealing from the companies’ accounts.

“As far as I know, [his associate and the DCOCC] didn’t mean this to go so far,” Gherman says. “All they wanted was to scare him and to make him give up his majority share [in the business]. But after I went to Tiraspol and met the interrogator, he told me the price of my brother’s freedom would be one million dollars.”

Ala and her brother’s fortune - even if they sold everything - could not cover such a high amount.

“The interrogator said my brother could easily find himself dead,” says Ala. “It happens quite often there.”

According to ex-detainees from Transnistrian’s penitentiaries, there are cases of prisoners who die by hanging, many of whom are unlikely to be suicides.

Ala understood that she was also at risk.

The interrogator called her after their discussion, telling Ala that his “men” could come to Moldova, drag her into a van and bring her to Transnistria.

“You think that if you’re in Moldova, you’re safe?” he said to her.

For the last two years, Ala has been campaigning to free Vitalie, while he stays detained in prison, without a trial to convict him.

His health is deteriorating and he has not seen his four year-old son for two years - missing out on spending time with him as he learns to talk, count and form relationships.

UN: Forced confessions common

The UN’s first official Report on Human Rights in Transnistria, published in 2013, describes extreme measures in the prison system to force confessions out of detainees.

UN expert Thomas Hammarberg visited Transnistria three times in 2012. He met with politicians, heads of the judiciary, prosecution and law enforcement, and with detainees and representatives of civil society.

The report shows that besides torture, the prison system has alarming problems such as overcrowding, prisoners with failing health and poor care.

In October 2012, there were 2,858 detainees in three penitentiary colonies for men and one for women in Transnistria. From these, 2,224 were convicted and 634 held in detention, like Vitalie.

This clocks up at approximately 500 prisoners for 100,000 persons - over three times the European average of 154.

Tuberculosis (TB) and HIV/AIDS are major problems in the colonies - with 54 infections of TB in two of the major prisons and tens of cases of HIV.

Ilie Cazac, a former tax inspector, accused by Transnistrian authorities of espionage, stayed in Prison Nr 1 in Tiraspol, where up to seven stayed in a cell for four people.

“People were dying all the time,” says Cazac. Removed to Prison nr. 2, he says there were two deaths every month, due to TB, AIDS-related infections, Hepatitis C and suicide by hanging.

Cazac argues that patients received no appropriate medical care, while medicine was rarely available. If any convict had a pain in the tooth, heart or head, the prison doctors would not supply them with drugs.

Organizations such as the Red Cross, Medical Rehabilitation Centre for Torture Victims – “Memoria” and the U.S and Czech Embassies have sent medicine to the prisoners. But these packages rarely reached the inmates.

Ernest Vardanean, a journalist and former detainee, claims that a pharmacy chain in Transnistria is owned by the head of the Healthcare Center of Ministry of Justice, which controls the prisons.

Vardanean alleges that this individual told him he would take the pills granted from international donors, for himself, using words along the lines of - “Guys, you must understand, I am a businessman, the pills must be sold.”

However, due to reporting restrictions in Transnistria, we could not verify this information.

Vitalie has a stomach ulcer, prostatitis and neurological and heart problems - but, according to his sister, the authorities denied him access to a doctor.

Since his detention, his health worsened due to the lack of adequate medical care and poor conditions.

However, the results of the medical examinations he undergoes in prison always show that his health is perfect.

“He spent six months in a cell with 24 beds, while there were 36 convicts,” says Ala Gherman, Vitalie’s sister. “They were taking turns to sleep in bed. Some of them had TB and HIV/AIDS. Since then, he coughs constantly.”

Private interest - State raid

Proving Vitalie’s innocence is tough, according to Alexandru Zubco, lawyer at Moldovan human rights NGO Promo Lex Association. This is because the case is of a financial nature and is complex for the authorities.

“Eriomenco’s enterprises are registered both in Chisinau and Tiraspol,” he says. “Here, he appears in the documents as the director, while in Transnistria he was forced to give up his shares. The case is manufactured; they have no proof nor witnesses.”

This is part of a trend which Zubco identifies as the ‘Soviet Raid’. An entrepreneur is making money. His rivals and/or associates are jealous. So they use their connections in Government, judicial circles and law enforcement to create a superficially legal justification to sequester their assets.

Eriomenco could seek justice in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). His case is under debate as it may violate Article Five of the International Convention of the Human Rights, granting everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. Eriomenco’s case is at an advanced level.

However around 60 former and actual detainees in the Transnistrian prison system are waiting for a decision from ECHR. If this rules in Eriomenco’s favour, the Court informs the two involved states - the Republic of Moldova and the Russian Federation (which de facto controls Transnistria), requesting them to pay compensation to the injured party.

Until now, ECHR has given three decisions regarding human rights in the region and the court has notified Moldova and Russia of 13 further cases of illegal arrest and detention. If ECHR gives decisions in favour of these 13 complainants, Moldova or Russia will be forced to pay compensation amounting to one million euro.

Before sending a file to ECHR, lawyers must gain evidence that the state they are suing has made concrete actions towards helping its citizens.

“Moldova has the main responsibility because the territory belongs to her,” says Zubco. “However, every time we send a petition or a request [to any Moldovian authorities], they say ‘sorry, guys, we can’t help you, come back when the conflict is over’.”

This ‘mini-cold war’ has now lasted 22 years.

When the lawyers mention the word Transnistria, the Moldovan authorities shrug their shoulders.

“It’s like a football game,” says Zubco, “they pass the ball one to another.”

Moldova’s Office for Reintegration aims to promote the government’s reintegration policy of the two territories, including the negotiation process for conflict settlement.

But its chief, George Balan, explains that Moldova has limited powers.

“Because of the totalitarian and authoritarian regime [in Transnistria], any kind of information is blocked,” he says. “We don’t know how many Moldovans or foreign citizens are in Transnistrian prisons. The figures in the UN report are the only ones we have.”

Eriomenco’s sister says that her attempts to find justice through the Moldovan authorities were unsuccessful.

When her brother was arrested, she brought the case to the attention of the General Prosecution in Chisinau. The office gave her an answer, which she paraphrases as - “If he was stupid enough to start a business there, then what can we do now?”

Balan says that he has not visited any penitentiaries.

“We don’t have real instruments to help,” he adds. “When we receive information about concrete cases, we make approaches to international organizations and raise awareness. We try to make it easier for the detainees by sending packages with food and presents on Christmas or Easter holidays.”

Chisinau: backdoor deals with Tiraspol

Although all information between the two states is ‘blocked’, there is proof of cooperation between the security authorities in Chisinau and Tiraspol regarding the supply of private information about its citizens, including children.

When Eriomenco’s family obtained access to Vitalie’s case, they discovered something that shocked them.

A letter sent on 22 December 2011 by Andrei Mejinschi, the head of Transnistria’s DCOCC to Gheorghe Tretiacov, the chief of Criminal Police in Chisinau, asked for information about Eriomenco’s parents, children and brothers.

The letter stated: “For investigation, we request information regarding residence visa, criminal records, goods and assets: houses, apartment, lands, enterprises, etc.”

It appears from the file that Moldova gave private information about its citizens to the breakaway Republic - which its authorities claim is a black hole full of Soviet-style apparatchiks with whom it is impossible to deal.

Ala Gherman sued the National Centre for Personal Data Protection and, as a result, the chief of Criminal Police sent her an official notice stating that they had broken the law.

Balan explains that the information trade was made on older agreements from 1999 and 2001 between the two Ministers of Internal Affairs in the field of criminal corruption. Both Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Moldova and Minister of Internal Affairs invalidated the agreement in 2005.

“However, the two Governments continued to exchange information after that,” argues Zubco.

On 23 April, the Center District Court from Chisinau issued a decision according to which Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) must pay, as compensation, 32,000 Moldovan lei each to Vitalie Eriomenco and the members of his family. This is pending appeal.

According to Gherman, any kind of recompense is “too late”

“The Transnistrians now know absolutely everything about us,” she says.

Since the sister of Vitalie complained to the media about his incarceration and torture, the Transnistrian authorities have prevented her from passing onto their territory.

Vitalie’s parents also never visit him in the prison. The only time when they can see him is during his hearings, where he sits in a white cell in a court room, waiting for a judge to decide whether to acquit him or send his case to trial.

Court - the only chance to see a son

I meet with Eriomenco’s parents and the Moldovan lawyer in June, as they prepare to visit a Tiraspol court for their son’s 38th hearing in 27 months.

In the courtroom there is a prosecutor, a lady who is silent during the whole meeting and the representative of the alleged victim, Victor Petriman, Eriomenco’s Moldovan and Transnistrian lawyers, a policeman in plain clothes and another in uniform, carrying a Kalashnikov.

The judge, Tverkovici Alexandr Borisovici, walks into the courtroom - wearing sunglasses.

Vitalie is in a blue shirt and looks pale. He sits on a bench, leaning towards the white bars of his cell, with his hands cupped on his ears.

His hearing has been damaged since his time in prison, probably due to blows to the head by interrogators.

Often he asks the judge to repeat the questions.

Every time he makes this request, the judge shouts at him: “I will not repeat the question again! Are you deaf?”

The witnesses do not appear. The judge and prosecutor take documents from Eriomenco’s lawyers. The proceeding lasts no more than 20 minutes.

“This is what they have been doing for two years,” says Eriomenco’s mother, Vera. “They play with us. We always come prepared, with documents and papers, but they don’t consider these. The witnesses never show up, so each hearing is a waste of time and money.”

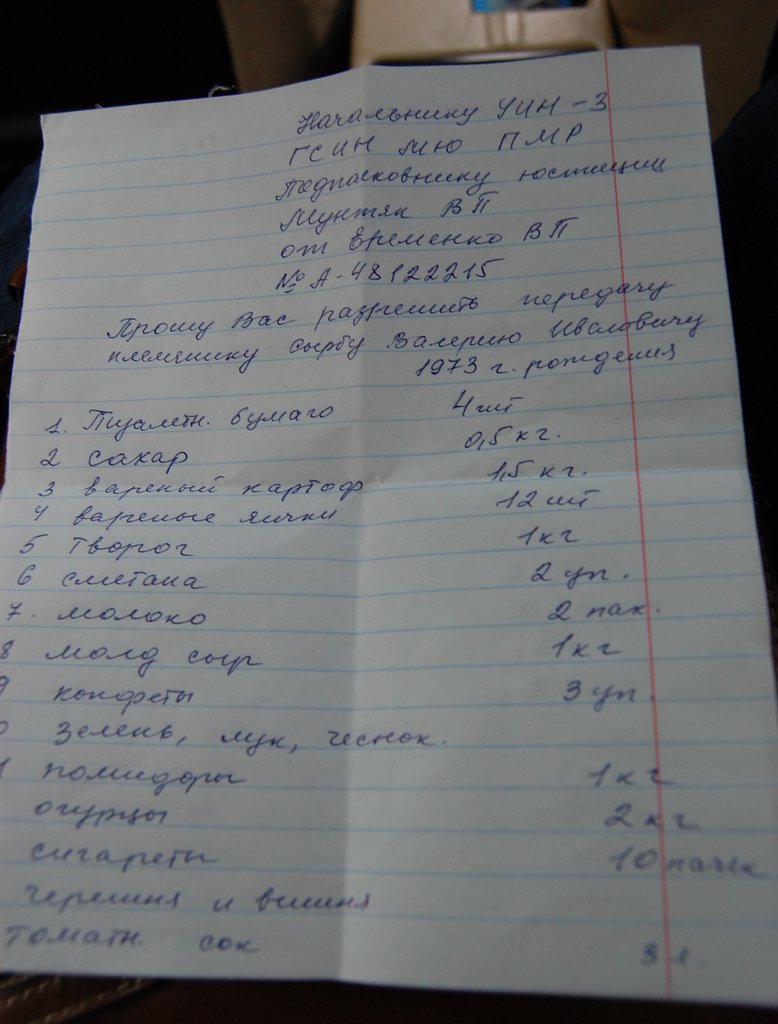

After the court appearance, we go to the Prison Nr. 3 to leave a food package for Vitalie. It is a balmy warm summer day. A group of women in uniform are chatting and eating ice-cream.

Outside the main prison door are packages of various goods - a broom, raffia bags, bottles of mineral water and soda, toilet paper, tomatoes and sunflower seeds. Meanwhile the friends and relatives of the detainees are sitting on benches or in their cars, to shade from the heat.

However clouds are beginning to pass across the sky.

Lida, a woman in a uniform, with short red hair, opens the small gates. The relatives rise from their seats, pick up their packages and rush to be first to get inside. I help Vera. We walk on a tiny path along a wire fence. Inside the building, we enter a room with dirty walls and a small window.

Usually, we must wait until someone calls our name through that window, but Vera is known by the prison staff. She often donates linen, radios, water and food to the prison. Every detainee has the right to a 30 kg package of food per month, but if the family wants to give him more, they must register this to the prison authorities as a donation for all the inmates.

We exit the prison gates and return to the car, where the driver and Eriomenco’s father, Tudor, are waiting to take us back to Chisinau.

The clouds above are now grey.

“So this is how our old age looks like,” says Vera. “Instead of growing up with our nephews and having a peaceful life, we buy food for our 43 year-old son, who is in prison.”

She is interrupted by Tudor, who looks through the car window, adding:

“It looks like it’s going to rain.”

Follow us