Three-way Art Battle for Streets of Kyiv

Found in a range of public spaces, on the facades of apartment blocks and in the entrances to city parks, mosaics and murals from the Soviet era could be considered some of the earliest examples of street art.

Yet throughout the former eastern bloc, much like communist ideology, such pieces have fallen into decay, are deemed longer relevant, or have been torn down and removed.

This erasure of the past has boomed in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, ever since the country’s president, Petro Poroshenko, enforced the country’s ‘decommunisation’ law in 2015. Now, any statue of Lenin faces the hammer.

But while one style of street art fades from the city’s landscape, another has emerged.

Following the protests in the city’s Maidan Square in 2014 against the Russian-backed President Victor Yanukovich, huge decorative murals etch the vast empty walls of blocks and factories across the city.

Centered on themes of patriotism and freedom, the artworks derive from the spirit of the protests, which strove to distance the country from Russian influence and foster closer ties with the European Union.

These two types of street art may seem very different on the surface, yet share a similar function as tools of the state.

However there is a third rival seeking to occupy the public space.

Against these forms of state-backed art is a new scene that challenges not only the government - but also rebels against traditional concepts of beauty.

Art as action. Not reflection

Lenin’s party slogan “it is necessary to dream” runs through the ideological veins of Socialist art. Following the 1917 revolution in Russia, theorists envisaged art as vehicle for realising these dreams. Art was action. Not reflection.

“Art as a method of knowing life…is the highest content of bourgeois aesthetics,” wrote Bolshevik journalist Nikolai Chuzhak. “A method for building life - this is the slogan behind the proletarian conception of the science of art.”

Works were designed to depict this society, even if it didn’t yet exist, through the intention that art would enable it to become a reality.

From the 1930s, under Stalin’s doctrine of Socialist Realism, characterized by the depiction of communist values, such as the emancipation of the proletariat, large public murals, mostly mosaics, were commissioned across the Soviet Union. Artworks promoted principles that were seen as intrinsic to the sustenance of a harmonious communist society, and tactically installed in places of influence.

In Kyiv, such pieces still exist, but mostly on the outskirts of the city. Venturing to the left bank of the river Dnipro, several are intact.

Guarding run-down housing estates in some of the city’s poorer districts such as Dniprovskiy and Desnianskyi, they are well preserved, proud monuments to the Communist state, a stark contrast to the crumbling tower blocks that surround them.

On the façade of a school buried between run-down Breznevka flats in the commuter neighbourhood of Troieschyna, is a piece by Ukrainian-born artist Volodymyr Pryadka. It still maintains its vibrant Soviet-red hues and promotes education, strength and unity (see above, first image on page).

Another, positioned on the edge of a busy ring-road nearby, depicts scientists, farmers and factory workers (below). Electric pastels merge the different professions together to highlight the importance of collective work.

Despite being in public spaces, Socialist street art was not created to cater for the tastes of the masses, but formulated by the intelligentsia, who aimed to shape the mentality of society.

Works received no independent funding and were entirely financed by the Government.

Artists were embedded in the inner circle of the Communist party, and put under pressure to create a clear vision of still-emerging party objectives. Failure to do so was interpreted as an indication of political disagreement with the party, which even if carried out subconsciously, would land artists in prison.

The Soviet Union provided the perfect environment for the experiment of shaping a new reality through art, as the effects of a revolution were more radical in the east than they were ever going to be in the west.

This is because the west was confined by its debt to tradition and previous intellectual, political and cultural achievements. The political shapers of the post-revolution east thrived off this advantage, associating tradition with inferiority, and thus Russia and the Soviet Union were more receptive to some new forms of art.

Walls of Freedom

Kyiv’s current political climate similarly provides an environment that allows ideologically-fuelled street art to thrive.

Works champion strength and freedom, and are mostly patriotic. Walking through downtown Kiev, there are an abundance of murals featuring national figures such as poet Lesia Ukrainka, dressed in traditional folk costumes and doused in the blue and yellow of the national flag.

While Soviet art was funded by the party, these pieces are funded in a similar manner, filtered through charities, NGOs and organisations affiliated with the Ukrainian government and the governments of countries aligned with Ukraine’s aspirations to be part of the EU.

One organisation that has curated many murals throughout Kyiv is ‘Art United Us’, which works in collaboration with city mayor Vitali Klitschko. Unlike Soviet artists, the creators of the organisation began their venture independently, but had to seek legal permission to create the murals in public spaces.

One of the group’s founders, Geo Leros, tried to bluff his way into the Kyiv city council to present his ideas - only to be detained by the security guards.

It wasn’t until a member of Klitschko’s team stepped in, that the organisation was granted a meeting with the mayor and received permission to decorate the empty spaces of the city. However there is little doubt that this would have happened if the organisation didn’t advocate the Government’s aspirations to be closer to the EU.

Like in Soviet times, the creators of this street art are embedded in the government, and Leros was awarded a role in Ukraine’s Ministry of Information.

Following the success of the project in Kyiv, Art United Us went on to continue working in collaboration with the Poroshenko-backed Government, curating patriotic art in Ukraine’s 'Anti-terrorist Operation’ zones in the country’s war-torn region of Donbass.

While post-revolution Russia provided a timely environment for the introduction of Socialist art, post-Maidan Ukraine provides an opportune landscape for Eurocentric tropes.

In cities across the Western world from Berlin to New York, street art has developed beyond the amateur, with its stencilists and muralists now deemed professional artists in their own right.

In a public space, the works are still associated with the rebellious roots and illegal tags from which they stemmed from and thus resemble a symbol of creative freedom.

Free from the confines of the gallery walls, graffiti works are often viewed as edgy tourist attractions.

Many artists commissioned to create murals around Kyiv are not from Ukraine.

Around the corner from the menacing Stalinist pillars of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stands a mural by Portuguese Alexandre Farto that pays tribute to Serhiy Nigoyan, the first person to be shot dead during the Euromaidan protests.

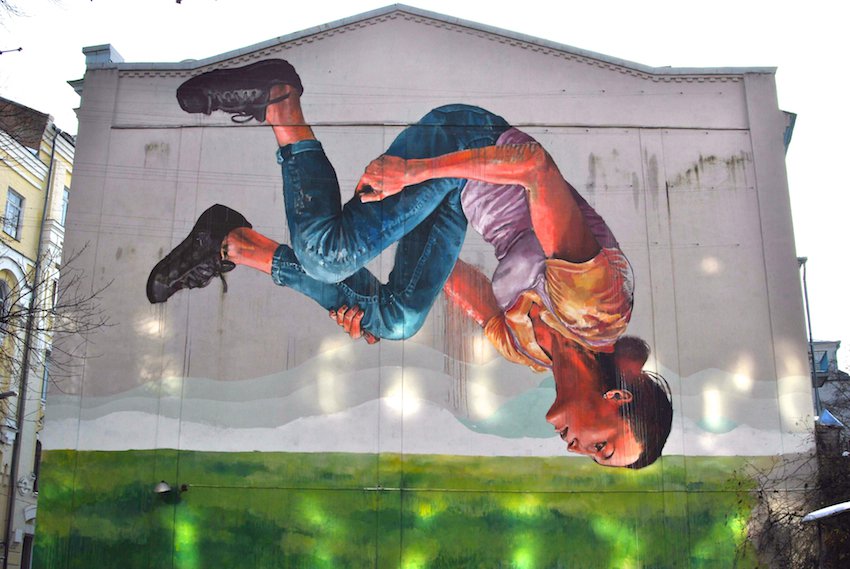

A piece by French artist Seth Globepainter has a prominent place in Kyiv’s old town, perched on a cobbled hill surrounded by touristic cafes and make-shift stalls selling trinkets and souvenirs, including toilet paper printed with the face of disgraced ex-President Yanukovich. Titled ‘Renaissance’, the work depicts a young Maidan protester wearing a military jacket and a traditional Vinok flower crown (above).

Another by Globepainter, tucked in a side street next to the ‘Heroes of the Heavenly Hundred’ boulevard, named as a tribute to the protesters who died under sniper-fire in February 2014, depicts two figures wearing colours of the Ukrainian flag breaking free from chains (two images above).

Artists from Brazil to Australia contribute work that is patriotic in its nature. According to Leros, who often curates the pieces, “artists from around the world are more interested in Ukrainian traditions and identity than local artists [because] local artists grew up with it.”

Through Ukraine’s desire to Westernise itself and to be viewed as a place that is free and able to adapt aesthetically to Europe, street murals can thrive and follow the same utopian function as Soviet art - through the hope that the depiction of this would enable it to turn into a reality.

Decommunisation Whitewash

Part of this Westernisation is the act of ‘decommunisation’, which culminates in the removal or adaption of anything associated with the county’s Soviet past.

Last May, the Government changed the industrial central city Dnipropetrovsk, named after a Russified moniker in 1926, to the shorter ‘Dnipro’. This also means a ‘lustration’ move, common in other east European countries, which is the act of purging officials with communist ties from parliament. But decommunisation extends beyond these to works of art.

Like in Moscow, many of Kyiv’s most impressive Soviet art works were not above ground - but in the underbelly of the city’s underground metro. However many of these works have now been stripped bare. While Soviet-era trains, rickety escalators and dim antique lighting remain, symbolic mosaics have been plied out and removed.

A sculpture of a woman inside a hammer and sickle that stood on the platform of the Polytechnic Institute station was targeted during the removals, and has now had her hammer removed (below)

Palats Ukrayina, which was originally named after the Red Army, is another station that underwent a significant make-under.

Once lined with crimson mosaics that paid tribute to the October revolution, the station had its Red Army soldiers removed and hammer and sickles torn out and covered with stark metal sheets (below).

The only artworks that are ‘safe’ are normally ones that are related to sport, such as Olympic-themed murals, or those that focus on nature.

Decommunisation is not only a symbolic dissociation from the country’s Soviet past, but the removal or adaption of pieces suggests that they are considered offensive, and damaging to current ideologies. To leave them alone would be to remain indifferent, yet their removal could be seen as a form of political censorship in itself.

“Spread maximum ugliness”

While mosaicked Red Army soldiers of 1917 are being forced to retreat from the city’s subways, a hundred years later – another revolution is going on, one that is regarded with as much disdain by the current government.

Kyiv has a strong underground graffiti scene, often occupying the walls of abandoned buildings and the underpasses of the city, blessed with wide boulevards and vast public parks.

One collective, whose tags can be seen throughout the city, proudly call themselves the ‘Save Ugly Crew’ (SUG).

While the huge murals made under projects such as ‘Art United Us’ were created ‘for the people’ by renowned graffiti artists flown from abroad, and in a similar manner, Soviet works were made by experienced elites, these underground works are created ‘by the people’, from a cross-section of society, none of whom make a living as professional artists.

One member of SUG, Nikito, tells us “we have everyone from a 16-year-old student, to a school teacher, to an architect who earns a good wage, to another guy who borrows money from his grandmother and drinks cheap beer.”

The group’s aesthetic is contrived to go against any pre-conceived idea of what society deems beautiful or, as Nikito puts it, to “completely destroy” and “spread maximum ugliness” throughout the city.

In an abandoned building near the city’s main train station, jagged and disfigured initials spell out the group’s tag, its ‘ugly’ aesthetic framed by soil-encrusted rubbish. In Pushkin Park, another is formed by lumpish alien-like creatures, their pudgy fingers probe the rusted foundations of a half-torn down concrete building.

Their disjointed scrawls can be seen on the side of public properties across Kyiv, and are put there without city council approval.

“My idea of making something ugly isn’t seen as something good for society,” says Nikito.

As under Communism, public artworks that aren’t viewed as beneficial in motivating society are treated as a defacement that should be punished.

“The government would only ever pay me to stop painting,” he says.

Nikito recalls that when he has been caught by the police, he has been slapped, beaten and choked.

“That’s our new police,” he says, “the same as they were before.”

It is clear that art that is funded by the government or some affiliated organisation is contrived to be positive in its message.

“When an artist paints on the walls he wants to share his subconscious,” Nikito says.

While he is insistent that he isn’t trying “to spread any message in particular” there is no doubt that the works SUG create are more true to the feelings of the artists, but also more pessimistic in sentiment.

Although the type of street art that SUG produces could be seen as reactionary, the fact that these artists are free from governmental and monetary control is what could arguably make their works the most honest out of the three.

While street art is in danger of turning into a corporatised entity, and already has been used as a means to give companies and political bodies ‘street cred’, SUG is a reminder that the medium doesn’t necessarily have to be doomed to this fate.

Instead, it reinforces the reality that it was a movement born out anarchism and freedom of expression, whose most beneficial traits lie in its ability to help society through its accessibility, community, audience interaction and social representation.

In the transitory period that Ukraine now finds itself with the prospect of political and social change on the horizon, there is no better time to reclaim the streets and build on a medium that has the possibility to serve the public as opposed to exploiting it.

A guide to the above images and their locations in Kyiv are mapped here

Follow us