Construction workers at Dilovası's newest road project are unaware they’ve been digging up a potential deathtrap. The ground beneath their feet, which they’ve been excavating for weeks, contains tonnes of illegally discarded hazardous insulation and asbestos-laden debris that forms a 12,000 sqm piece of land that the locals call ‘Izocam Hill.’

The Black Sea exposed the existence of the hill back in 2019 as part of its Toxic Valley project, which investigated the consequences of 30 years of unbridled industrial expansion in Dilovası, a small town close to Istanbul that is one of the most polluted areas of Turkey.

At the time, we worked with an asbestos expert to collect samples for testing in an accredited lab. The results showed massive amounts of glass wool and rock wool insulation materials. Mixed in with this was fibre cement that contained three types of asbestos: crocidolite, chrysotile, and amosite.

Evidence of the provenance of the illegal landfill pointed to nearby Izocam, Turkey’s first-ever manufacturer of mineral wool insulation, and was among the first companies to open a factory in Dilovası back in 1965. It is owned today by the French Saint-Gobain and Kuwaiti Alghanim Industries. Former employees and locals said the company had routinely dumped factory waste in the hills of the town.

The Black Sea revisited Izocam Hill last month. Workers from subcontractor Menga Insaat told us they were unaware of any dangers from the job and were not provided with any special equipment.

"I didn’t know anything about this area. I only knew it used to be a landfill, but our superiors never warned us that it was risky,” one excavator operator said. "We have been working here for weeks; I hope we won't have any problems. We are dumping the soil we extracted down the slope. If there were a problem, [our superiors] would probably intervene.”

Despite knowing for years that the hill contains harmful insulation waste and asbestos, Kocaeli municipality did the unthinkable: they started to dig it up.

Workers are “navigating in the dark”

Experts say that a single microscopic fibre in the lungs can kill so asbestos is at its most dangerous when released into the air, where, if inhaled, can cause mesothelioma and other cancers. The consequences of exposure often take decades to appear and are impossible to cure.

For this reason, asbestos removal is strictly regulated by law. Dr Yücel Demiral, a professor at Dokuz Eylül University and an expert in occupational safety and health, said the construction is “dangerous” and should halt immediately.

There are no circumstances where workers can safely operate in the area, he said. The asbestos needs to be removed by qualified experts under lawful conditions. "To ensure that there is no asbestos in the air that a person breathes, they should use a completely closed system that we call 'scuba'.” This means hazmat suits, air-tight tents and decontamination procedures.

The current conditions pose a serious risk to workers and anyone with whom they later encounter. “Workers can carry asbestos home on their clothes,” he said “Their wives and children can be exposed. The asbestos present right here can become a concern for the whole community." Right now, he added, the workers are “navigating in the dark.”

We contacted Menga Insaat, but they did not reply to our questions. Locals confirmed that work at the site continues unabated.

“They created a mountain here”

Izocam Hill has sat on the edge of Dilovası’s Orhangazi neighbourhood since the 1980s and has always been treated with caution by the locals, who would complain of rashes and breathing problems after being in the area. Local shepherds said that their flocks would get sick or infected feet if they roamed too close.

In March, Ahmet Durmaz, a father of three who lived beside the hill for decades, said that the illegal dump formed over time until it extended to the front of the residential area. “This area is covered with Izocam all throughout,” he said. “They created a mountain here. It should have been cleaned but Izocam brought this filth, piled it up, and that was it."

He believes that the authorities are negligent by failing to inform the community about yet another health risk or consult them on the new road proposals. "Everyone in Dilovası already has asthma, no one can deny that. They didn't inform us in any way about building a viaduct.”

The Black Sea contacted Saint-Gobain. Laure Bencheikh, head of media relations, told us in an email that “the mineral wool products manufactured by Izocam do not, and never have, contained asbestos” and that the company only ever used authorised disposal sites, echoing similar denials from five years ago.

Izocam Hill has never been an authorised dumping site. The company did not explain how massive amounts of glass wool, rock wool, and ‘Eternit’ – fibre cement roofing and the source of the asbestos – ended up there or how they knew for certain it was not Izocam waste.

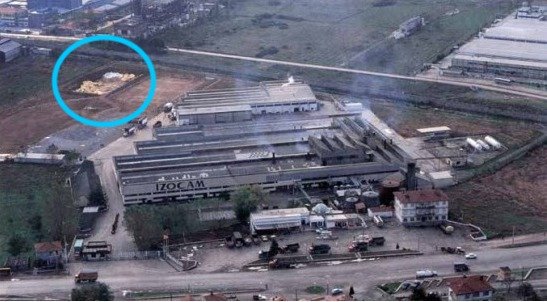

Back in 2019, we published a photo of Izocam’s Dilovası factory from the 1980s, which former workers said shows a dumping zone for faulty wool and building debris, which they would then transport to the illegal landfill outside the village.

A photograph of the Izocam factory in the 1980s (credit/TBS)

“It was swept under the carpet”

For years, the Kocaeli municipality, which governs Dilovasi, largely ignored the problem. On at least one occasion it attempted to cover it with dirt and plant trees, which all died. After the Black Sea’s report in 2019, locals made efforts to compel the municipality or Izocam to clean the site.

Ismail Sami, the chair of Dilovası Ecology and Health Association (EKOSDER), told us, "No one knew there was asbestos there until The Black Sea gave it coverage. After the news, it became an agenda item.”

He discussed the matter with the Head of the Environmental Protection and Control Department of Kocaeli Metropolitan Municipality, who expressed concerns that any efforts to properly dispose of the material and rehabilitate the area would cause the asbestos to spread over Dilovası and create a more serious problem.

"This meeting did not happen just once; it happened many times,” Sami added. “A public health expert even came to the municipality and discussed this issue with the mayor.” When the head of that department left office, it was never discussed again. “It was swept under the carpet.”

Before the road construction began, the municipality spread dirt across the area. “I’m saying ‘covered up’ only as an expression. They didn't even completely cover it with soil."

Drone shot from 2019 of the illegal dump, highlighted in red, now the site of the road construction (Medyascope)

"It would have been better if they just left it there"

While leaving the hill untreated posed a public health risk, the decision by the municipality to authorise construction now increases the danger immeasurably. “What they are doing is simply dangerous,” said Dr. Yücel Demiral.

"They release something into the air that was perhaps covered up. The asbestos is spreading around uncontrollably with this process. So, it is not appropriate to continue working like this because now they are digging up something that was static, and it is being released into the air.”

The purpose of the road is to connect the Orhangazi and Turgut Özal neighbourhoods, and this generates additional concerns over the construction’s proximity to new settlements that include a hospital and school, with plans underway to build a nursing home.

The presence of potentially vulnerable residents makes the situation "even worse,” said Dr Demiral. "This is an open area with settlements nearby. There is a potential for all living things to be exposed. We can say that school children have a greater risk of mesothelioma and cancer.”

"School children have a greater risk of mesothelioma and cancer" from asbestos (Credit/Vedat Oruç)

The dangers of Izocam Hill are not confined to the asbestos. The discarded mineral wool, made by melting glass or rock, requires intervention because, as Dr. explained, “these are fibres which can cause allergies or other immune-related diseases.”

Environmental engineer, Utku Fırat, told The Black Sea that, under Turkish law, a single complaint to either the Kocaeli or Turkish Environment and Urbanisation departments requires the government to investigate and remove the hazard. There is also the potential for criminal sanctions for “pollution of the environment through negligence,” he said. “The Ministry of Environment and the prosecutor must work together to inspect the dump site. Then, criminal sanctions could be imposed after the culprits are determined.”