The son-in-law of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Berat Albayrak, helped establish an offshore structure in Malta and Sweden to evade millions of dollars in taxes for his company - Turkey’s massive energy, textile and construction conglomerate Çalık Holding.

In the end the devious structure was not needed for Albayrak, who was then-CEO of the Turkish multinational.

Why? In 2015, he moved into his new position - as Turkey’s Minister of Energy and Natural Resources. In this role, he pushed through preferential Tax Amnesty legislation written by his former Çalık associates. The law, called the ‘Wealth Peace Act’, would permit Çalık to repatriate unlimited amounts of offshore cash. Tax-free.

Albayrak’s offshore dealings are exposed in a combination of leaked financial documents and the Redhack e-mails as part of the European Investigative Collaboration (EIC) network’s #MaltaFiles.

They raise serious questions about the government’s penchant for political favours towards big business, and Çalık Holding specifically, which in the past has received billions in government incentives.

Mission: bring the cash home from Dubai

An email dated 4 November 2011 contains a clear warning: “Brother, the new system will be established - but this system will be based on tricking the [Turkish] finance authority; it’s not a secure system. If the finance authority discovers this, it wouldn’t be good for [Çalık’s] reputation.”

The author of the note is Metin Atalay, Çalık Holding’s man in Dubai.

The recipient is 33 year-old Albayrak, then CEO of Çalık, which has interests in textiles, real estate, telecommunications, mining and energy. This is owned by billionaire Ahmet Çalık, a close friend of President Erdogan. Albayrak is also the husband of Esra Erdoğan, the president’s eldest daughter.

According to the leak of Albayrak's e-mails, Atalay was hired to run Çalık’s office in one of Dubai’s Free Trade Zones, which are tax-free citadels designed to attract foreign investors.

He is a strawman whose “job does not matter” as he was hired to “only [be used] for the delicate matters”, referring to signing documents, with no questions asked. This is because Çalık in Dubai is little more that a shell to collect the fruits of the company's worldwide business activities. And it is a profitable arrangement - the offshore operation is bringing in millions each month. For the first half of 2011 alone, the Dubai company Çalık Enerji FZE's holdings are 34.7 million USD, according to Atalay’s emails.

Çalık wants to bring this cash home. But a direct transfer from Dubai to Turkey means paying 20 per cent of this - and future profits - to the Turkish tax authorities.

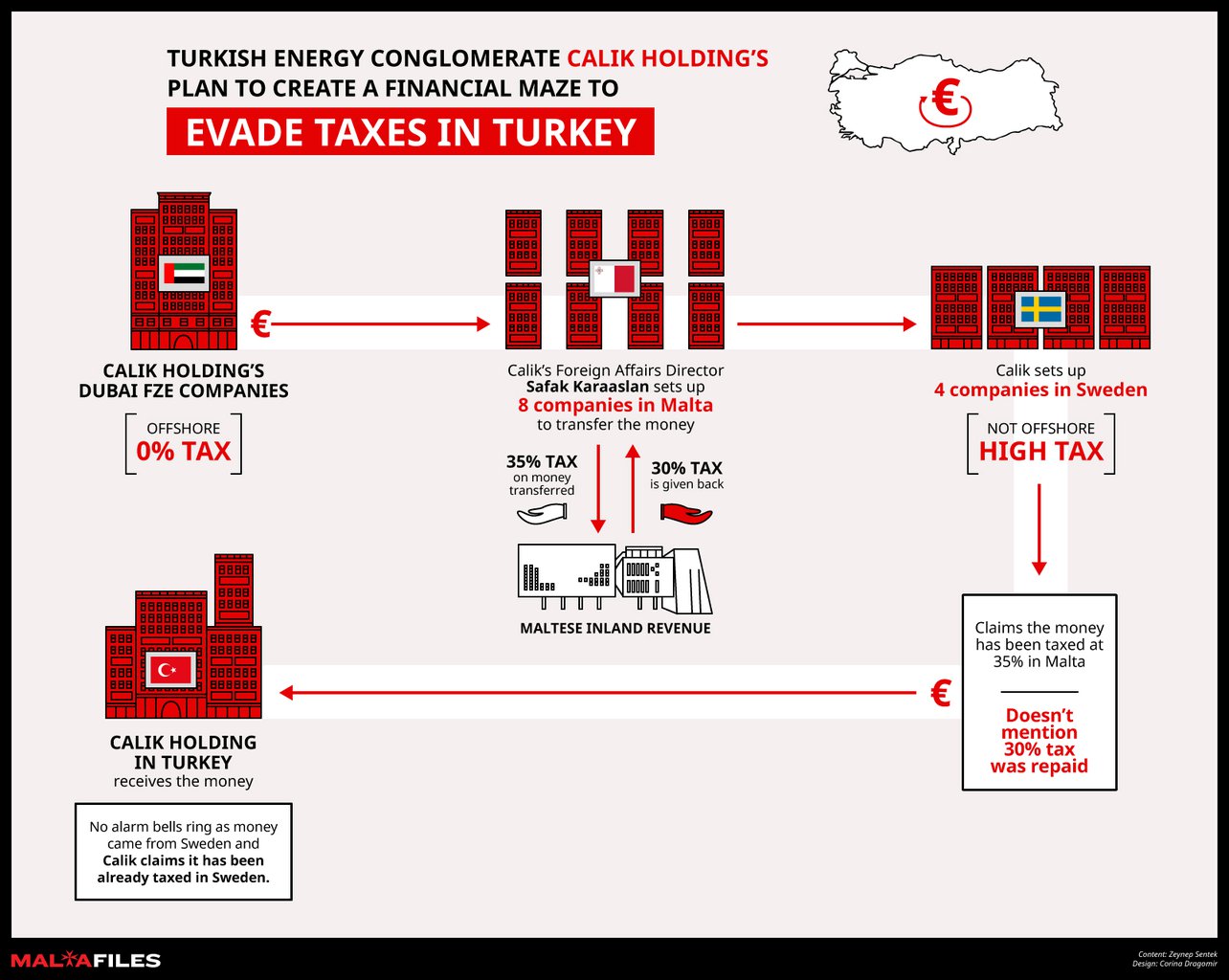

How do you get money from Dubai to Turkey, while paying as little taxes as possible? The mission falls to Çalık’s Foreign Affairs Director, Şafak Karaaslan. His answer is to establish an offshore structure through Malta and Sweden.

Çalık’s plan is to transfer the Dubai millions to bank accounts of companies in Malta, paying 35 per cent tax to Maltese authorities. This seems bad on paper. But check the small print. Because Çalık's shareholders do not reside in Malta, nor does the company undertake significant activity on the Mediterranean islands, the company can apply for an 80 per cent refund, effectively creating a tax rate of only five per cent.

With the cash now in the EU, it can shift to accounts in Sweden. By falsely declaring to Swedish authorities that it already paid 35 per cent in taxes in Malta, Çalık avoids further deductions.

When the money is finally brought to Çalık in Turkey, the tax authorities are fooled into believing it is from a high-tax and reputable jurisdiction in Scandinavia, so no alarm bells ring.

Here is a picture of the scheme:

Atalay is unconvinced about going through with the plan. But his chagrin is mostly fuelled by his reluctance to move his family from Dubai to Malta. He tells Albayrak that Çalık should forget the complicated tax scheme and instead “wait until [the Turkish government] offers a tax amnesty” - parliamentary bills that allow the tax-free and legal repatriation of offshore funds. “We are talking about Turkey,” Atalay writes, “there is always a tax amnesty [coming].”

Atalay doesn’t give up. A few months later, on 24 January 2012, he emails his boss, Şafak Karaaslan, and complains further about the new system that would see him relocate to Malta.

Karaaslan wants to press through with the plan: “I’m just laughing and can’t say anything,” he responds. “[Çalık] compulsorily takes a decision regarding tax planning in accordance with its interests.”

Over the next year or so, Karaaslan works on the scheme. In 2012, he incorporates four new companies in Sweden - Çalık Textile, Çalık Energy, Çalık Marketing and Çalık Construction. The following year, he opens eight more limited companies in Malta: Fashion Zone Textile Holding, Fashion Zone Textile, Synergy Marketing Holding, Synergy Marketing, Technological Energy Holding, Technological Energy, White Construction Holding and White Construction.

Today, these companies are in liquidation, and only one of them was ever declared in Çalık Group’s Turkish annual reports: Çalık Energy in Sweden, which was listed as “inactive”.

Similarly, none of the company accounts in Malta or Sweden reveal cash transfers, and Çalık never moved Atalay to Malta, as planned.

This is because Çalık had no need for a complicated and potentially illegal scheme: Albayrak was on his way to the top.

Prince of the new Turkish elite

At the end of 2013, months after the Maltese companies were established, Berat Albayrak resigned as CEO of Çalık to run as an MP for Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) in the June 2015 Turkish elections.

Unsurprisingly, he was victorious, and five months later he was appointed as Turkey’s Minister of Energy and Natural Resources.

Berat Albayrak is the son of conservative writer and President Erdoğan’s good friend, Sadik Albayrak. In 2004, Berat married Erdoğan’s eldest daughter, Esra. Educated and connected, he became CEO of Turkish business giant Çalık Holding in 2007, when he was only 29 years old, after working for the company since 1999. Çalık's chairman, Ahmet Çalık, is a close associate of Erdoğan and has ties to numerous foreign leaders.

From March 2007 until his departure for politics in 2013, Albayrak presided over a company that grew ever-closer to Erdogan’s government and ever richer, earning billions in public tenders.

A year following Albayrak’s promotion to CEO, Çalık bought Sabah-ATV, Turkey’s second-biggest media company and owner of the Sabah daily newspaper, which had been seized by the government. Çalık was the sole bidder for the tender, offering a 1.1 billion USD bid, which is said to have been financed by loans from two Turkish banks and Qatari investors, according to Turkish news reports.

Despite having no background or experience in politics, Albayrak has led the Turkish Energy Ministry since November 2015. Many now believe that Erdogan is grooming Albayrak as his successor. Albayrak joined Erdogan on his recent visit to the U.S. where the pair were filmed together outside the Turkish Embassy in Washington, looking at their security detail beat up peaceful protesters.

But it appears that his former company is never far from his thoughts.

“Don't call it a tax amnesty”

Five months after his cabinet promotion, Şafak Karaaslan sends a message to Albayrak on his private e-mail address. Attached is a document called “New Money Centre Again”. It explains how the U.S. refused to join the Common Reporting Standard, a global anti-money laundering initiative to share financial information between nations. This is good sign that Turkey will not have to do the same.

So it might be the ideal time for Çalık to finally move its Dubai millions back home.

“There are two options left for people who have wealth abroad,” Karaaslan writes. “They either take their wealth to the USA … or states can make it easy for citizens to bring their wealth back.”

“Designing a tax amnesty which will guarantee privacy will help [Turkish] citizens to bring their wealth back into the country…” he adds. “Because as time goes by, this needs to move fast. People need to be informed about this really well and people who own wealth need to understand its importance.”

Albayrak needs little convincing, it seems. A month later, on 3 June 2016, Karaaslan sends another email to the energy minister - with yet another attachment. It is a draft bill for a new “tax amnesty” to be presented to the Turkish parliament.

Karaaslan sells the law to his government friend, and even suggests its title: “Wealth Peace” “As we know, the CRS [Common Reporting Standard] has been signed,” he writes. “The USA is the exception, so most probably, world trade and bank accounts will direct [money] towards the USA. Turkey can use this to its benefit… It can achieve this through a Wealth Peace.”

“We specifically are not using the word ‘amnesty’ here,” Karaaslan writes.

He also advises Albayrak that the law should needs to be marketed well. “Before this becomes law,” he adds, “the issue needs to be promoted very well. People need to be informed about the information exchange system [CRS] and should get worried about it so they will see [this] law as a good thing and as an opportunity.”

Even though Karaaslan's draft bill is similar to a previous tax amnesty law passed by the Parliament in May 2013, Çalık’s Foreign Affairs Director adds his own touches.

“Even though we think this one was generally a good law,” he writes, “we are including additional points where we think the law is lacking.“

Karaaslan’s “additional points” include allowing companies or individuals to repatriate money – electronically or physically - with no questions asked until the last day of December 2016. He also generously deletes an article which taxes funds coming into Turkey at two per cent.

Additionally, Karaaslan’s law allows the appointment of external parties to transfer cash on others’ behalf, without any legal rights for the state to investigate the source or beneficiaries of the money, nor prosecute anyone who might be committing crimes.

Minister to business leader on law draft: “Final version. Is it OK?”

By June 2016, Albayrak is now operating as a conduit for the new law, ping-ponging emails between Turkey's Finance Minister, Naci Ağbal and Calik's Karaaslan. The law even finds itself going to the big man himself - Erdogan. Unofficially, of course.

On 21 June Albayrak forwards the attachment to Erdogan’s private secretary, Hasan Dogan - in a move that raises serious questions about constitutional boundaries.

Even though Erdogan's loyalty to the AKP is no secret, the implication that he actively inserted himself in the business of the party's policy making might breach Turkey's constitutional laws which demands the president “takes no sides” in political matters.

There is no evidence that Erdogan or Dogan responded to Albayrak's transparent gesture. But the next day, the energy minister e-mails his old friend Karaaslan with the copy of the bill, asking, “Final version. Is it OK?”

Two days later, Turkish prime minister, Binali Yıldırım, offered a new 'Draft Bill to Amend Laws to Stimulate Investment' to the parliament, including the 'Temporary Article no.2', containing the Wealth Peace provisions, written by Çalık’s Karaaslan.

Çalık’s 'Article no.2' caused mayhem in the Parliament, with opposition MPs claiming it would open Turkey’s doors to illicit money. Opposition parties threatened to block the whole draft consisting of 77 articles if the AKP refused to remove the Article no.2.

On 14 July 2016, the AKP caved. Özgür Özel, MP for the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) declared a victory, vowing to fight it again if it reappeared.

The victory was short-lived.

The next day factions within the Turkish army launched a coup against the government. In the weeks that followed, parliamentary business was pre-occupied with passing state of emergency laws to tackle the rebels, and attacking the network of the exiled-preacher, Fetullah Gülen, the man many believe was responsible for the coup. Amid the chaos of the government’s crackdown, mass arrests and firings, however, Çalık Holding had not forgotten its priorities.

A week after the coup, 22 July 2016, the Budget Commission added Çalık’s Wealth Peace provisions to another draft bill and sent it to the parliament.

The text was more concise, but little had changed. The bill passed in little over a week, and was sent to President Erdoğan for his approval. On 18 August, he signed the “Wealth Peace” - legalised money laundering - into law.

Mehmet Bekaroğlu, CHP Member of Parliament told The Black sea that “[Turkey's] economy is in shambles. We are trying to find money everywhere, that's why they enacted this law,” he said. “I asked the Ministry of Finance and posed questions in the parliament many times about this law - who brought in money, how much and if the money even stayed in the country afterwards. I was told they do not hold any information. There is clearly a problem here.”

Çalık declined to answer The Black Sea’s questions, stating only that our allegations are “not accurate and we strongly deny these claims. Our group has never been in involved in any illegal practices.”

Ministers Berat Albayrak and Naci Agbal did not respond to requests for comment.

Picture Albayrak: Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources