The Hague, Netherlands. 24 September 2015. Rain and wind. A hit of Autumn. Five people leave the headquarters of the International Criminal Court (ICC), the judicial body financed by 124 nations to prosecutes war criminals and mass murderers. Among the group is Kerry Propper, a Wall Street banker and philanthropist dedicated to combating genocide.

Next to him is the foreign minister of the Kurdish region in Iraq and three representatives of interest groups Yazda and Free Yezidi. They support the cause of the Yezidis - a religious minority targeted by Islamic State (IS) in Iraq, where 10,000s were ethnically cleansed from their homes in the town of Sinjar.

On the front steps is a press conference, which only a handful of journalists attend. But from the entrance, the officials want to show the world that someone, somewhere cares about the fate of these victims. They want to make the point that, despite silence in the international community, it is possible to bring the war criminals of Islamic State before a court. After all, that is why the International Criminal Court exists - to crush the world’s bullies.

Inside the court, they have spoken with the ICC’s chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, to plead for an investigation into atrocities against the Yezidis.

They handed her a report packed with facts and testimonies. The IS massacre of Yezidis on Mount Sinjar in 2014. The young boys abducted and brainwashed to become new IS fighters. The ongoing violence against thousands of girls and women, who are held as sex slaves.

Bensouda has listened, and if the lobbyists have this global justice enforcer on their side, and she takes up the case, there is a chance for justice.

But what should have been an honest defence of a persecuted minority transforms into a fiasco that upsets the court’s rules and procedures with false declarations and conflicts of interest, as we reveal in #courtsecrets - documents obtained by French website Mediapart, analyzed by NRC and journalism network European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) [for more information on #courtsecrets read our explainer]

Nothing the Court can do against Iraq and Syria

Five months earlier, in April 2015, Bensouda issued a statement saying there is probably nothing she can do against Islamic State (IS), because the terror group primarily operates in Syria and Iraq, countries that do not recognize the ICC’s jurisdiction.

There is a legal detour. Many IS fighters are from countries who do sign up to the court, including many in Europe. These fighters could be brought to justice. The interest groups are convinced it can be done. In their report they collect additional evidence against IS fighters from outside Iraq and Syria.

But this is an indirect route to justice. The prosecutor’s job is to concentrate on the chief instigators of war crimes and genocide, who are most probably Syrians and Iraqis.

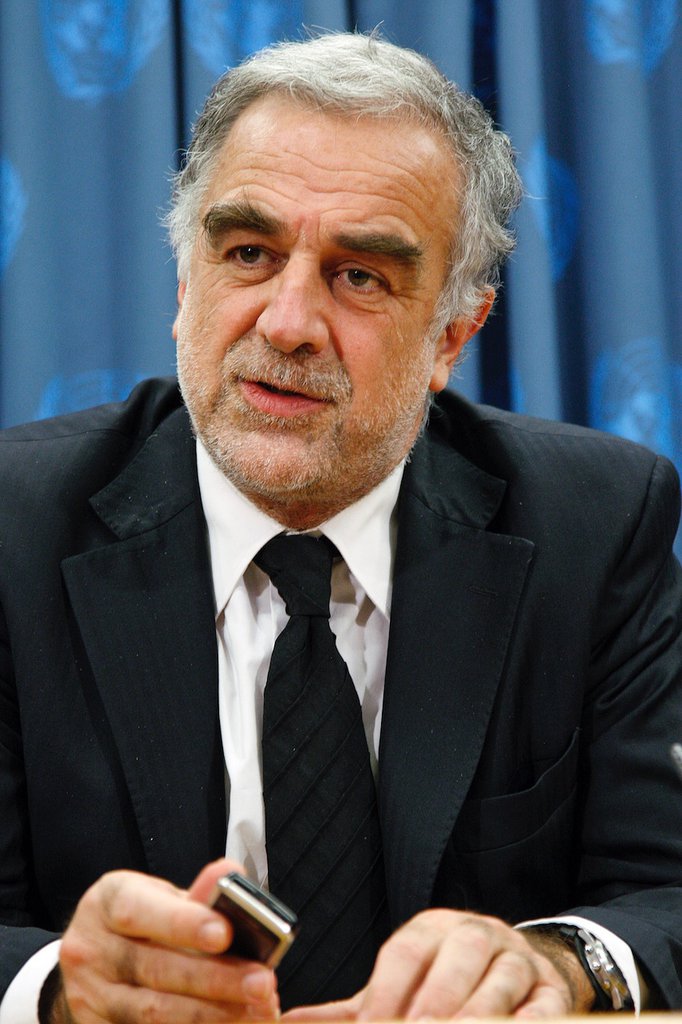

Yazda and Free Yezidi are helped by the best ally they could wish for: the Argentine lawyer Luis Moreno Ocampo. Between 2003 and 2012 he was first chief prosecutor of the ICC. During those years Bensouda was his deputy prosecutor.

Since leaving The Hague, Ocampo lectures at Harvard, and works as a lawyer and consultant. In August 2015, the American banker Kerry Propper, a board member of lobby group Yazda, asks him to help with the Yezidi mission.

Propper leads a double life, he says in interviews. He is the CEO of an investment bank and an activist raising awareness about genocide. First the Holocaust and Rwanda, and this time the Yezidis. He wants to lobby key states, the United Nations and the ICC. Ocampo's network must open these doors. Propper gladly pays the expenses.

Ocampo does the job pro bono. The website of his current consulting practice in New York, Ocampo Moreno LLC, devotes a lengthy article to his efforts for the Yezidis.

“Mr. Moreno Ocampo decided not to personally engage the ICC because of his former role as the first Chief Prosecutor. Instead, he outlined the process and the requisites for Yazda to present the Yazidi situation before the ICC.”

This means that Ocampo helps the lobby groups, but does not contact his former employer - the court - directly, and he does not take part in The Hague delegation in September 2015.

But his statement on a lack of personal engagement is not true.

The documents in EIC’s possession show that Ocampo did contact chief prosecutor Bensouda to promote the Yezidis’ cause. They also show that one of Bensouda’s employees at the Court is asked to handle money to use in the lobbying process, revealing a clear conflict of interests.

Ocampo to Bensouda: “I can explain to you the Yezidi case”

A few weeks before the delegation’s trip to ICC, Ocampo asks Bensouda per email if he can call her “to explain to you the Yazidi case and ask you what to do about it”. She agrees. The next day, he tells a former staff member of Bensouda that he spoke with the chief prosecutor “to provide her clarity on what [the Yezidis] try to do and achieve”.

This former ICC employee is Olivia Swaak-Goldman, who worked as an international cooperation advisor in the Prosecutor’s office during both Ocampo’s and Bensouda’s tenure. She has been away from the court for two years, but still has good contacts there. Ocampo asks her to assist in the lobby. Kerry Propper agrees to pay her 3,000 USD for the assignment.

Swaak will arrange and prepare the meeting between the interest groups and the prosecutor. Ocampo tells Swaak he is working on the report that the delegation will hand to Bensouda.

Documents show it is mainly Ocampo's legal assistant, also a former staff member of the prosecutor's office, who writes the report. Ocampo advises her on legal issues to be included, and the interest groups provide witness statements. Yazda and Free Yezidi however are the only authors mentioned in the final version.

The meeting is to take place between September 20 and 25 2015. When Olivia Swaak does not receive confirmation on the date, Ocampo approaches his successor at the court, Bensouda, for a second time. The delegation needs to plan its trip to The Hague, he writes in an email. Bensouda replies that she has just instructed her staff.

The court does not have specific rules about how a former prosecutor should relate to his successor. But it is clear that the chief prosecutor must remain independent at all times. Bensouda receives requests for help from groups all over the world. She can only pursue the most important and promising cases, and must be able to justify her selection.

So if Bensouda were to investigate the plight of the Yezidis despite her earlier rejection, it must be clear that this is her independent decision. Not an attempt to do her former boss a favour.

Ocampo turns to one of Bensouda's current employees for his mission. Florence Olara is a spokesperson for the prosecutor and also worked for Ocampo when he was in office.

“Staff may not accept instructions from outsiders”

For Olara, there are clear office rules. A code of conduct has been in place for the Office of the Prosecutor since 2013. It says, among other things, that staff may not accept instructions from outsiders and not do anything that could affect the confidence in the independence of the office.

Yet these rules are tested when Ocampo asks Olara to organize the Yezidi press conference. From an email by Ocampo’s legal assistant, it is clear that Olara is aware of the conflict of interest.

The assistant writes to Ocampo that Olara is not feeling comfortable.

“Especially the fact that Flo [Florence Olara] works for the court and is not supposed to be organising the press conference.”

The delegation cannot use Olara’s name in front of the prosecutor, she warns. This is even more apparent, because Bensouda wants the meeting to remain confidential. This need for secrecy does not seem to fit well with a press conference on the Court’s front steps.

The assistant to Ocampo writes: “Would it be possible to run all the correspondences through you or me, or as Flo suggested, to use a fake email I created for her using a pseudonym?” She says Olara “cannot put her job on the line for this”.

So Olara uses a false name, Oliver Tuscany, when she asks Ocampo for 8,000 dollars to organise the press conference. She promises to arrange the presence of major international media. Ocampo tells his sponsor, Kerry Propper, that Oliver Tuscany is a “partner” of Olara, and that Olara cannot join openly because she still works at the ICC. Like Ocampo, Propper seems to have no objection. But he thinks the requested sum is too high. Olara has to settle for 5,000 dollars.

Through her lawyer, Olara states that she did not organise the press conference, she did not get paid to do so, and that she spent that day at her work. Olara adds that she never used a false identity.

But some of these points do not cohere with Kerry Propper’s statement. When we asked the philanthropist why he let Florence Olara organise the press conference and media outreach, while she was also working for the Office of the Prosecutor, he replied: “I was told she has good press contacts.”

Fear of “increased expectations”

Bensouda is upset when she finds out the press are on the doorstep, and when Reuters publishes a report mentioning that the Yezidis personally met the prosecutor. She is afraid this will increase expectations among the persecuted groups, or disappointment if she does not start an investigation.

Again, Ocampo sees no problem. He considers the press conference the most important part of the trip to Holland, he writes to Propper. Bensouda has no right to keep genocide victims from expressing their sorrow, he says to the team. He urges Yazda and Free Yezidi to spread the Reuters report among the Yezidis in refugee camps in Iraq.

Bensouda did not start an investigation into the crimes against the Yezidis after she received the report.

Two months later, Ocampo wants to send another delegation to The Hague. This time, he is helping victims from Venezuela. Bensouda declines. She lets it be known that the Venezuelans can deliver their report, but that she has no time to receive them personally.

The court already has enough false expectations and disappointments.

What do the current and former prosecutors say about this today?

While Ocampo has lobbied Prosecutor Bensouda on many occasions, the current Prosecutor said in statement that her bureau “refrains from initiating contact or engaging with Mr Ocampo” since he left office.

“The Office in fact has a clear position on this matter and we, as a matter of policy, do not seek advice, consult or engage Mr Ocampo in any of the situations or matters before the Office or the Court. On the contrary, Prosecutor Bensouda has also clarified this position to Mr Ocampo and has asked that he refrains from any public pronouncement or activity that may – by virtue of his prior role as ICC Prosecutor – interfere with the activities of the Office or bring it into disrepute. Mr Ocampo does not speak for, or, act on behalf of the Office.”

Bensouda and her office treat their independence and impartiality as “sacred”, her statement says.

Luis Moreno Ocampo did not respond to questions on this subject from EIC

Who is involved in the #courtsecrets project?

Initiator: Fabrice Arfi (Mediapart)

Reporters: Fabrice Arfi, Stéphanie Maupas, Fanny Pigeaud (Mediapart), Sven Becker, Marian Blasberg, Dietmar Pieper (Der Spiegel), Hanneke Chin-A-Fo (NRC Handelsblad), Amanda Strydom, (ANCIR); Michael Bird, Zeynep Sentek, Craig Shaw (RCIJ/TBS); Blaž Zgaga (Nacional); Alain Lallemand, Joël Matriche (Le Soir); Paula Guisado (El Mundo); Stefano Vergine (L'Espresso); Micael Pereira (Expresso); Jonathan Calvert, George Arbuthnott (The Sunday Times)

Tech and info-design: Alex Morega, Gabriel Vijiala (RCIJ/TBS); Stephan Heffner (Der Spiegel); Nicolas Barthe-Dejean, Donatien Huet (Mediapart); Marien Jonkers (NRC Handelsblad)

Project Guide: Ștefan Cândea

Pictures: UN, ICC, Wikimedia