Q: What does a Romanian woman do with a blank piece of paper?

A: She reads her rights.

This joke encapsulates the country’s attitude towards women and domestic abuse. Romanian society is aware of the damages that women suffer, but refuses to take such pain seriously.

“Regarding domestic violence in Romania, we’re stuck in the middle ages,” says Valentina Rujoiu a professor in the University of Bucharest’s Faculty of Sociology and Social Assistance.

Here we detail the reasons why Romania fails its battered women

1: “Men know best”

Women in abusive relationships face criticism from a patriarchal mentality which often elevates woman’s duty as a wife and partner over her personal safety.

Many Romanian women are raised on the idea that a married woman must please her husband and do anything that he expects of her.

That is why marital rape is seen - by most women I spoke to - as not part of physical abuse and not a crime in itself.

Many women are expected to stay with their husbands rather than risk the stigma of separation.

According to Rujoiu, the myth persists that “the divorced woman is guilty for not being able to keep her man at home.”

Eleonora, an abused woman who won a divorce after 20 years in an abusive marriage, argues that after her separation, there was the supposition that she was available for every man.

She - a breast cancer survivor in her 50s - still experiences such an attitude from her male neighbors, who constantly proposition her in the street.

Women also do not control the reins of the state. The Romanian Parliament is only 11.5 per cent women. But for those who do succeed, they often adopt the attitudes of their male colleagues.

Mihaela, a victim of domestic violence who recently won a restraining order against her abusive husband, tells me that the judge in her case - a woman - gave her a divorce against her partner’s wishes.

In her final judgement she stated by that Mihaela “had not been a victim of domestic violence” and argued - using a contemptuous tone - that she only managed to win the divorce because “the complainant used favorable legislation”.

Meanwhile Romanian society is changing. Especially in the service industry, women are ascending the career ladder faster than men - and many are the breadwinners in their family.

Nevertheless the stigma is still prevalent that men should be in charge of family finances, even if they are unemployed.

One abused woman married to a jobless man told me that his attitude was always: “His money was his money, my money was our money”.

By controlling family incomes, men can blackmail women into remaining in abusive relationships.

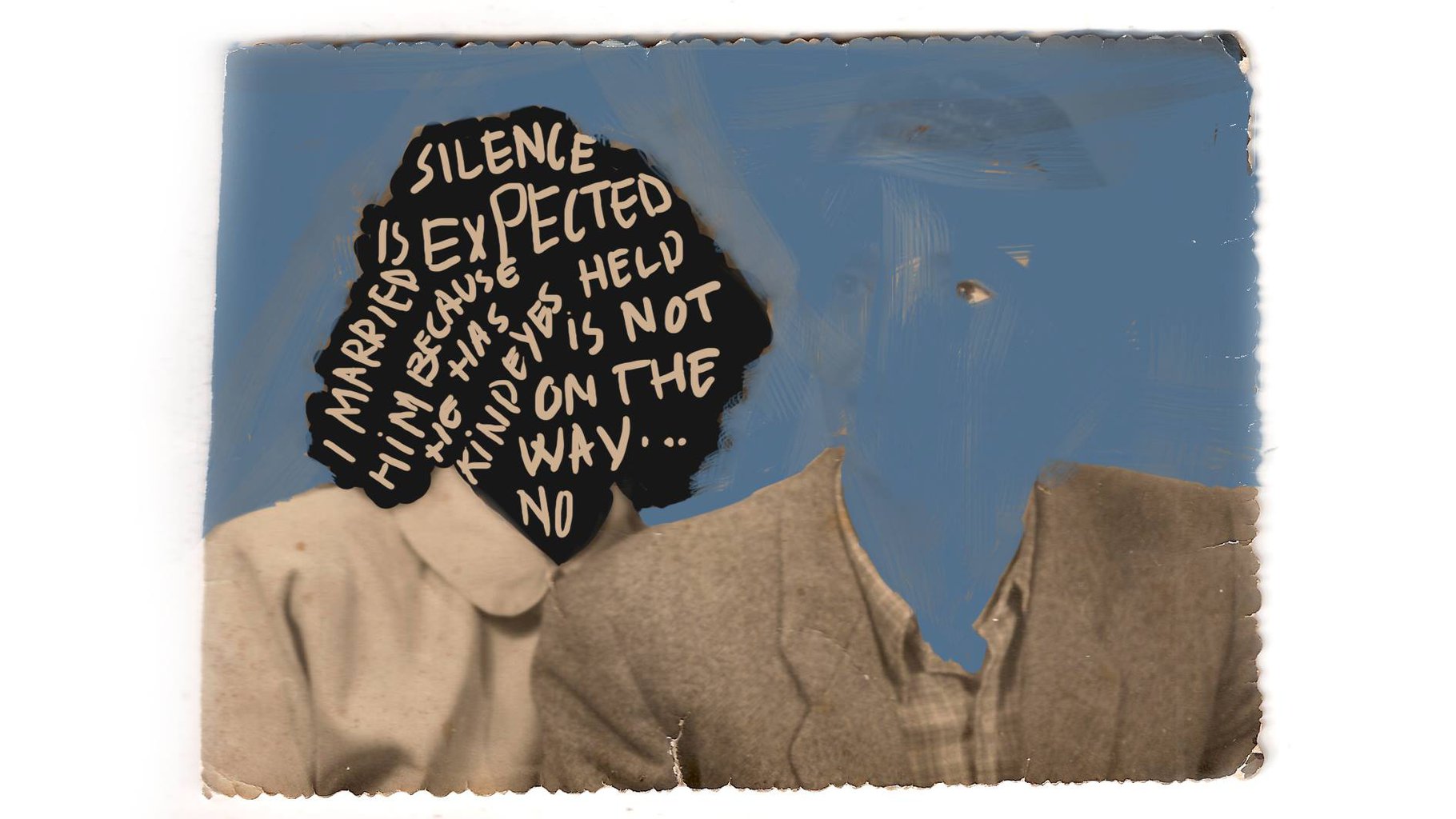

2: “Silence is expected”

In Romanian households, there is still the concept that what happens in the house stays in the house.

According to a poll by INSCOP for Romanian newspaper ‘Adevarul’ 50 per cent of people believe domestic violence is a private matter.

In the same poll, 30 per cent of Romanians believe women are sometimes beaten up because "they deserve it"

3: “To be beaten is shameful”

One of the obstacles to women seeking help in an abusive relationship is the fear of judgement by the woman’s friends, relatives, neighbors and colleagues.

“Sometimes the women victims are judged by their families, but mostly by society,” says Valentina Rujoiu.

This is a problem of changing the mentality of the authorities.

“Everyone judges women victims,” says Mihaela Mangu, director at ANAIS Association, a Bucharest based NGO that offers free legal counseling to victims of domestic violence.

“Automatically, when a woman tells you that she was beaten by her husband for 30 years, but she has five children with him, you think, well why did you stay for so long?”

In the countryside women are many times surrounded by the shame of what the neighbors will say when she files a complaint against her own husband.

“In the rural areas, it depends on whether the community accepts such practices,” says Simona Burduja, psychotherapist at the Sensiblu Foundation, which provides counseling and a shelter for victims.

“A woman doesn’t know that she’s in an abusive situation because if the lady next door experiences the same thing – and says nothing – it means this is normal.”

4: “I didn’t know it was abuse”

Madalina lives in a small town in Transylvania and has been in an abusive relationship for 16 years.

Her husband attacked her, threatened to take her children away from her and stopped her from moving around town alone.

Only when randomly searching on the Internet did she begin to realize that these were the symptoms of domestic violence - and that she had the right to defend herself.

Women have little access to information about their rights, including recognizing the signs of domestic violence and having the tools to escape from an abusive relationship.

“Many women do not know what domestic violence is,” says Mihaela Mangu. “Many people associate domestic violence only with physical abuse.”

Legally, women have rights. Since 2012 abuse means physical, psychological, verbal, spiritual, economic and sexual - but this change is not well-known.

Also few women are aware that marital rape is a crime.

5: “Authorities do not care”

“I have two kids and I live with my husband. He came home one time and hit me. I screamed for help, hoping that some of my neighbors would come to help me. But no one came.

"He struck me against the floor and whenever I was trying to get up he would strike me again.

"I went to the police station. I asked the policemen to let my husband know that I have rights.

"The policemen asked me: ‘Do you want me to give him a fine?’

"I said: ‘What does it help me with if you fine him with 150 Euro? That’s the money for my children. I want you to make him aware that I have rights.’

"The police told me that if I can’t stay in a relationship anymore, I should get a divorce and not ‘argue like a gypsy’ at the police station.”

In 14 of Romania’s 41 counties there are no specialized services for victims of domestic violence.

A large number of police officers are not trained in how to communicate with an abuse victim.

They cannot recognize the signs of post-traumatic stress disorder or Stockholm Syndrome - the situation where abused women sympathize, defend and remain with their abuser.

There are also few mixed teams of male and female police officers to tackle the problem.

“We don’t have an extended network of specialists in domestic violence, and the police are not prepared to deal with this,” says Rujoiu.

6: “Help does not exist for all”

Abuse victim Ioana lives in a large town in north Romania. She contacted me desperate for help.

I searched to find her free psychological counseling in her county.

I called the local social services. From the central office, I was directed to a department that purportedly covered domestic violence or abused women.

The woman who answered the phone did not introduce herself. She asked me "What do you want?".

I said I know a woman who is in an abusive relationship with her husband and that she needs free psychological counseling.

She told me: “Well - if the lady is abused by her husband, then why is she still staying with him?”

She said the Social Assistance department only offers counseling to women in their care.

“If the lady does not want to leave her husband, there is nothing we can do.”

Many social workers do their best to help abused women, but Valentina Rujoiu considers that the country lacks specialists regarding domestic violence and that this is an under-financed domain which needs training.

Due to a lack of consistent social care, NGOs and religious groups often step in to help women victims, but they cannot offer national coverage and lack oversight of their activities.

Outside of Bucharest and Romania’s bigger cities, the options for help for abused women are limited.

7: “No one to call”

If a woman in Romania believes she is a victim of domestic violence, she may want to talk to someone about her situation.

But there is no emergency number.

Recently I put up my phone number in the comments section of an article about domestic violence asking if any victims of domestic violence would like to contact me to tell me their story.

I received a call from Ioana, a woman who has been in an abusive relationship for about 20 years. She said she was about to slit her wrists. She thought I was from an emergency hotline.

I said I wasn’t equipped to help her, but we talked for a couple of hours. She wondered if there was a number she could call.

I asked around, but could not find one. The only one I found was in the Romanian-speaking Republic of Moldova.

It seems if Romanian women are on the verge of suicide following years of abuse from their husbands, their only chance of help is to dial up another country.

8: “The right laws are not working”

Although the legislation has become more supportive towards abused women in the last decade, the forces of law and order are still unprepared to manage cases of domestic violence with consistency.

In Romania the restraining order was first introduced in 2012, following a case where a husband shot dead his wife at her workplace, after she had filed complaints to the police.

Courts in Romania issue around one order a day.

Though a useful instrument, sometimes the restraining order does not work properly.

For instance, Mihaela, an abused woman, applied to a court and won a restraining order against her husband. But the moment it expired, he started threatening her over the phone.

She asked for a second restraining order and the court told her that she can only use the order to prevent physical abuse. The former husband who still sends her threatening texts is now applying for custody of the children.

According to experts, it is unclear what sanctions exist for aggressors who violate the order.

Moreover, Andreea Braga from Centrul Filia, an organization promoting gender studies, tells me: “for an application for an order to be succesful, a woman needs to make a formal complaint to the police, a forensics certificate and at least two witnesses, who are not her relatives.”

These are major obstacles as abuse usually happens at home. In the case of Madalina, the only witnesses were her children and, when she shouted for help, none of her neighbors intervened.

Meanwhile the modus operandi of Mihaela’s husband was to grab his wife by the hair and strike her against the floor, leaving no marks. A forensics expert told her that she needs bruises, blood or cuts for a certificate to prove abuse.

Restraining orders should be an emergency instrument - but they take time to obtain.

Andreea Braga states that - on average - a woman has to wait 33 days.

For most women, this is 33 days too long.

A Romanian version of this article appears here on TOTB