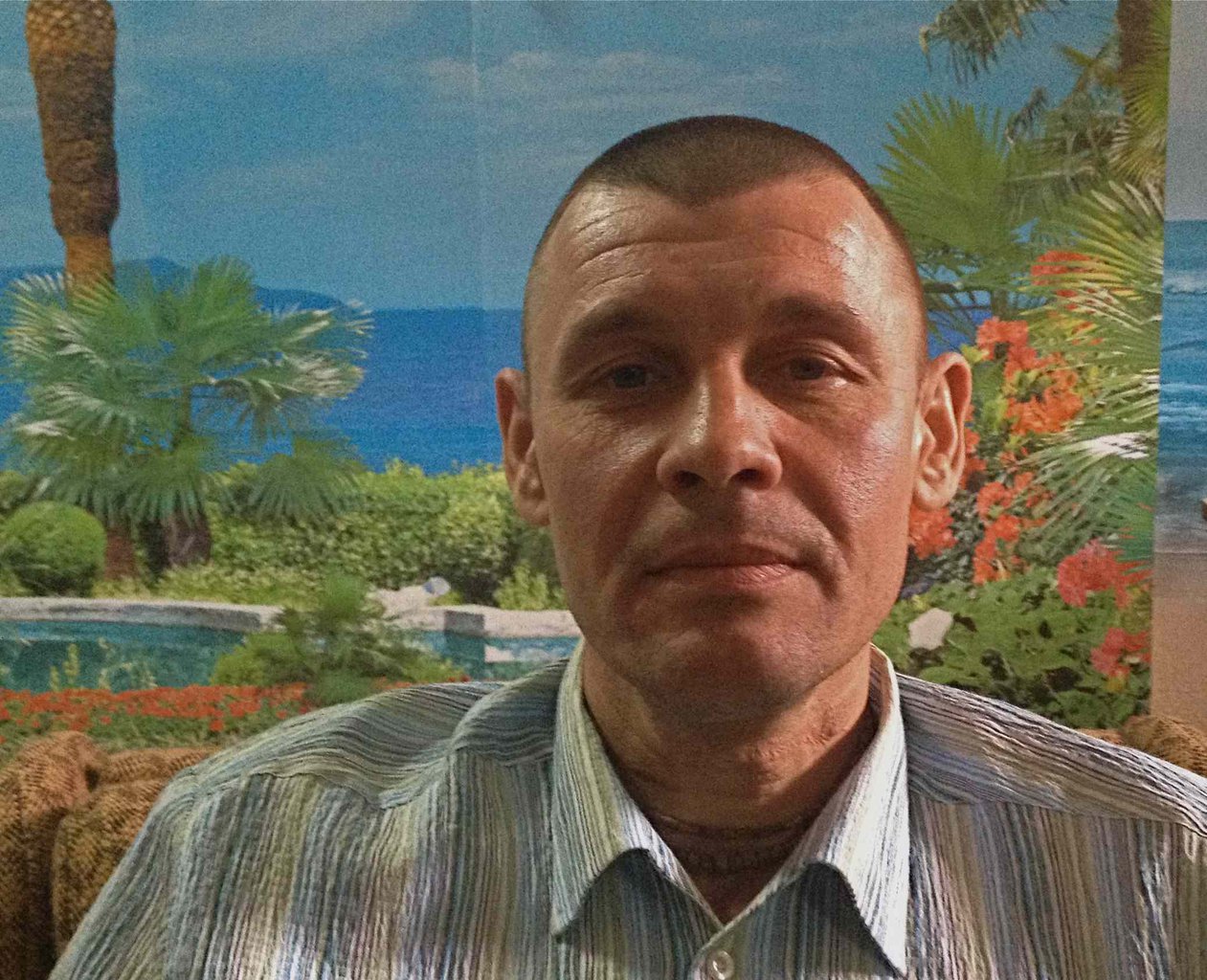

A former amateur boxer and soldier, 42 year-old Yuri, is reminiscing about his veins.

Once they were raised and prominent, like those of a professional fighter, rippling across the muscles of his arms and chest. A sign of toughness. Training. Discipline.

Now he shows me his broad arms and firm chest, pointing out how his blood flows in narrow strips of blue, hidden deep in the flesh.

“This is due to 15 years of injecting drugs,” he says.

A resident in Tiraspol in Moldova’s breakaway region of Transnistria, Yuri has no fears of speaking out about opiate abuse in a police state unrecognized by any United Nations country.

“All the people and powers know what I was, what I did and who I am now,” he says.

As a soldier for the USSR, he served in the Azeri-Armenian conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh between 1989 and 1991.

“I continued serving after there was no USSR, but there was still a Soviet army,” he adds.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, he began to drink opium tea. But when he noticed his fellow soldiers started to inject a mixture using poppy, he followed.

Back in Tiraspol in the 1990s, he cooked his own concoction, called Shirka, based on the home-grown poppy that local bakers sprinkle on buns and bread.

The process took about 45 minutes. Yuri would grind down the poppy seeds, add water and soda until they become a paste, which he steamed in acetone.

This left a tar, to which Yuri added acetic anhydride - a compound that drug cooks use to convert morphine into heroin. He mixed this with a sedative and put in a syringe for injection.

“We used to make it in the forest or a kitchen,” he says.

Yuri used this home-brew heroin from 1991 until 2006.

During this time, he had no job, so turned to crime to fund his habit.

But this was not easy.

“My hands are not made for pick-pocketing,” he says, unfurling his bear-like fingers.

Yuri stands up and demonstrates how he and a colleague would steal from passers-by in the street. His heavy frame would bash into someone - he would place his hand in their pocket, remove their wallet and, while the passer-by was confused, Yuri would chuck the wallet to an accomplice.

The victim would scream that his money was gone and Yuri would shout back:

“You think I did that? Then search me.”

He also forced doors open with his backside, broke into houses and flats and opened car doors with scissors, stole cassette players and sold them on the black market.

Jail recipe

In Transnistria, the authorities sent Yuri to prison three times. He spent most of his term in the ‘Zona’ - a colony of narrow buildings set about a yard, with sports halls and space for around 1,500 inmates.

In the prison, he continued to inject. But finding the right ingredients was hard.

First he needed the poppy. This would come from outside. When the inmates were playing football in the yard, a contact from Tiraspol would throw a bag of poppy-seeds over the walls.

One prisoner caught this, threw it to another, who threw it to a third. The prison guard tried to intervene, but because nobody kept hold of the package, no one was in possession of the drugs.

As the guards tried to work out what was going on, someone hid the stash.

“Sometimes the guards caught it and sometimes they didn’t,” says Yuri.

Inside, he bought needles from doctors, but to activate the poppy mixture, he needed acetone. To extract the chemical, he would boil down around 30 empty plastic lighters into a paste, which released the pure gas.

I am confused. I ask him to repeat what he just said.

“Yes,” he says, “we boiled down thirty plastic lighters into a paste, which released the pure gas.”

He pauses.

“You don’t invent these things in England,” he says.

In the prison, there were 20 cells in a corridor.

One inmate had a jar with poppy product for 20 uses. He asked along the corridor who had the needle and who had the vial. The guard passed them from one person to another for a small amount of cash.

Using the sandpaper of a matchbox strike pad, Yuri filed down the needle to make it sharp, then he took a strip off his trousers, tore this into pieces and lit this up. This helped heat up a metal cup of water. He put the needle and vial into the cup to sterilize this before injecting.

Yuri left prison the last time in 2006.

“Since then, I tried not to do drugs,” he says. “I did it from time to time. My daughter was growing up. Most of my friends were dead, 15 of them to AIDS and five to overdoses. I wanted to change my life and also I found spirituality."

Krishna versus Shirka

Yuri grew up in a village close to Moscow, before moving to Transnistria as a teenager.

“In the USSR we were told there was no God,” he says, “and we have proof. Yuri Gagarin went to space and he did not meet God.”

His father was a communist and his mother a teacher.

“My mother had to carry my older sister 14 km to the next village to get her baptized,” he says. “At that time the KGB was telling off priests for baptizing Communists.

"If the police had known she was a teacher and married to a communist, she would have had to show a piece of paper saying she was divorced for them to allow her to baptize the baby.”

In the Army, when he saw fellow soldiers die, he started believing in some kind of higher authority.

“When I returned from the war, I was screaming at night and hitting the walls,” he says.

“I met a friend who had been in Afghanistan and had gone through a spiritual education. He invited me to Riga to a communion of Hare Krishna. There I made a promise not to hit anyone and not to eat anything connected to death. The centre was like a regiment for gladiators. You had to wake up at three o’clock in the morning.

"At that time, I didn’t make it - I couldn’t do the meditation and philosophy. I was still young and I wanted women.”

Since then, Yuri continued to have problems with injecting drugs and drinking.

“But,” he says, “I tried not to hit anyone or eat meat.”

After prison in 2006, he joined the Tiraspol-based NGO ‘Healthy Future’ as a volunteer to meet and converse with others who wanted to quit.

“At the beginning I came to group therapy,” he says. “The best one is he who speaks from his own experience. I saw that and I stopped using and drinking alcohol. Since I was six years old I was a smoker, but now I have given up.”

The centre also gave users the chance to speak about their faith - conversing in a personal way about the God in which they believe, free of the restrictions of organized religion.

While the spirituality gave him hope, the therapy offered him the means to understand himself with more clarity.

“Once or twice a year in the season I go back to Shirka,” he says. “but God is checking on me.”

Now Yuri is looking for funding to create a greenhouse to grow plants, so that ex-users can create an enterprise to give addicts the chance of a career.

At the end of the interview we talk outside in the courtyard of a four-story Soviet-era block.

He reaches into a small woolen bag and produces a piece of card.

On one side are the days and months of the year 2013. On the other is a picture of a blue child in a turban, a ring of flowers and pearls around his neck and his arms around a baby cow.

“This is Govinda,” he says. “The cow gives milk. The cow is the symbol of life. Life,” he repeats, his thick index finger thumping on his chest. “Me.”

Opening picture copyright Petrut Calinescu