Half a million abandoned kids: moving forward from southeast Europe’s history of shame

Half a million children were left abandoned in eastern Europe following the collapse of Communism that began in the 1980s.

After more than 25 years of democracy, many of these countries’ record on child protection is now mixed.

In 1997, while global concern focused on abandoned children in Romania, 1.66 per cent of the country’s kids were separated from their families.

By 2013, this had dropped to only 1.52 per cent.

This means 60,000 children have been recently cut off from their parents, according to the new Child Protection Index, a cross-border instrument launched this week in Brussels.

Most southeast European nations - including Romania - are fast to reform their laws, but changes are slow to improve the life of every child.

Belgrade, 2016. A tiny conference room, packed with civil society activists who have fought for children’s rights from the wider Black Sea and Eastern Europe since the fall of Communism.

Armenians, Georgians, Bulgarians, Serbians, Moldavians, Romanians, Albanians, Bosnians and Kosovars look at the findings of a comparative study as though they were the pass, dribble, tackle and assist of a football match.

A whisper rises up from the Bulgarian delegates.

“Romanian really undid us on this one,” comes a voice.

Despite the collegiate atmosphere among the members who all put the needs of children way above national interest, there is a still time to entertain rivalry between the EU’s two poorest countries.

The study has been developed in nine nations and shows how the lives of these “invisible” children changed over the last twenty-five years.

Romania was the country with the largest problem - with its abandoned kids running into the 100,000s.

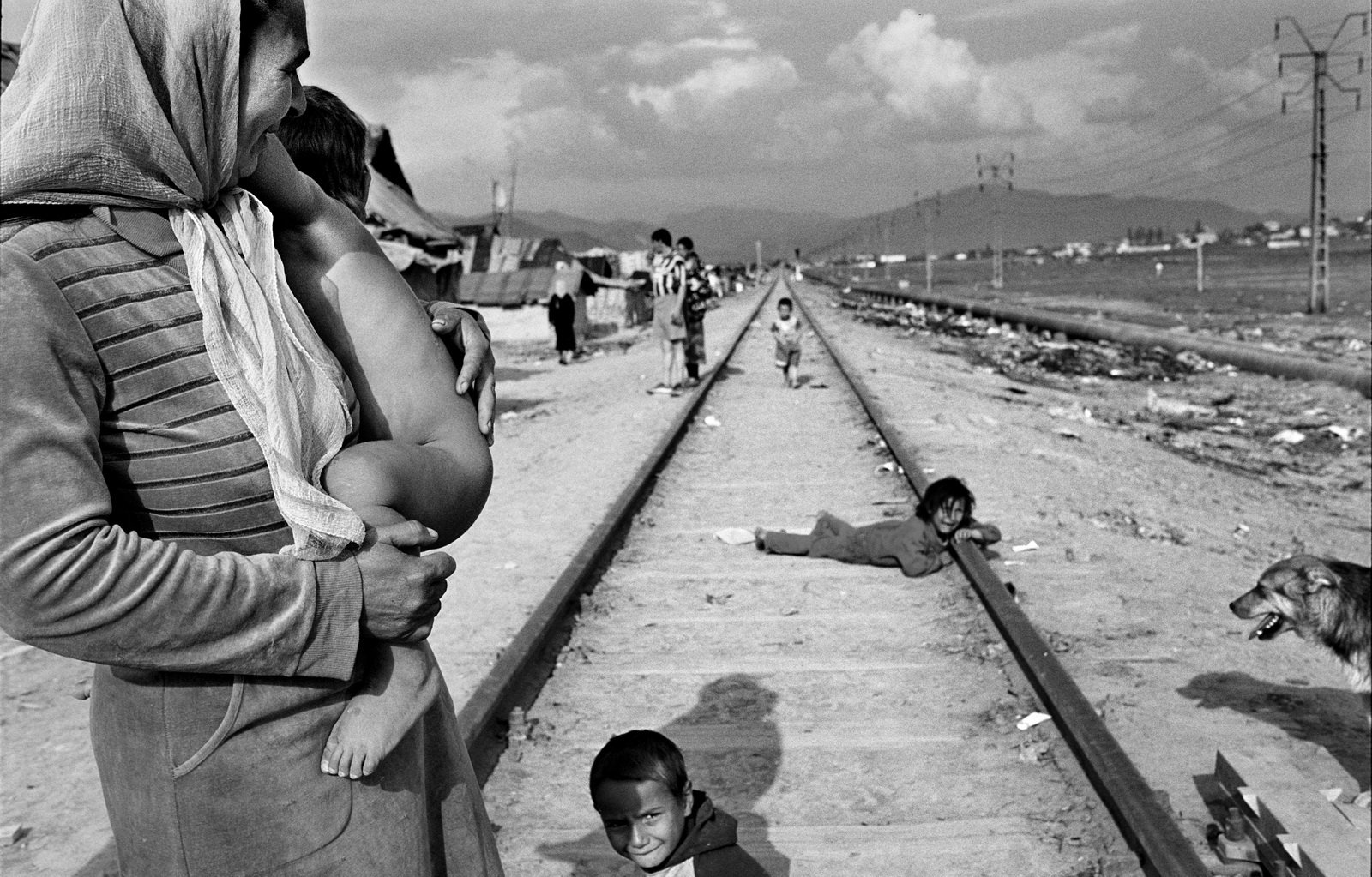

The images of abandoned children after the fall of its Communist regime remain scars on the European collective conscience.

To stop the population decline in Romania in the 1950s, due to more working women and a fall in living standards, the Communist Party aimed to boost the numbers of Romanians from 23 million to 30 million.

In 1966, in a move to raise the birth rate, Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu de facto declared abortion and contraception illegal.

This resulted in parents abandoning children in hospitals after birth. The state then placed the kids in overcrowded institutions.

With the break-up of communism in 1989, the doors opened to a humanitarian crisis.

Today ChildPact is the only regional alliance that includes more than 600 child rights organizations. For the ten national members, ChildPact is the friends they grew up with; with whom they shared the same playground and the same stories. They know the group dynamics, the pacts and rivalries, the sensitivities and small victories.

Romanian doctor Andy Guth pours over comparative charts showing which child protection reform models worked in spite of the east European national systems, and which tend to be corrupt and underfinanced, with low levels of economic development, bad laws and zero methodology of implementation.

“At the back of the institution: an image that still haunts me”

Spring, 1990, in Romania. Guth was a recent graduate from medical school and fledgling director of an orphanage in Onești. Here he was signing two of the first transfers to a hostel for ‘irrecoverable’ children, the official term for mentally or physically disabled minors.

These children were clinically healthy when they were admitted.

“Two weeks later, we received the first death certificate," he says. "I immediately went to the hostel. The first thing I saw when I got out of the car was the graveyard behind the institution. They had their own graveyard!”

For Guth, this was ground zero - the initiation point for the child protection renaissance that would follow seven years later.

“It’s an image that will haunt me for the rest of my life,” says Guth.

Guth was one of the doctors on the frontline of humanitarian convoys in the nineties, facilitating the programs drawn up in offices abroad. They were known as ‘The White Guard’.

Many became civil society activists, who still play an active role in the reform of child protection.

Why did doctors take on such a role?

During Communism, medically-trained personnel were tasked with raising deserted children in unheated buildings that served as town hospitals. This abandonment was seen as a public health issue.

Twenty-five years later, Guth is presenting the results of the Child Protection Index, an international instrument whose development he dedicated four years to, coordinating the collaboration of 71 child protection experts from nine countries. He has worked on the project together with Jocelyn Penner Hall, World Vision’s Policy Director.

This has some disturbing information.

“One baby abandoned every six hours”

In Romania, the number of children separated from their families in 1997 was in the range of 100,000 for six million kids.

By the end of 2013, the number hovered around 60,000 for a total population of four million.

Taken together this amounts to a statistically insignificant change, from 1.66 per cent in 1997 to 1.52 per cent in 2013.

One reason for this is a gap between reforms on paper, and those on the ground.

For instance, between 1997 and 2007, Romania was pressured by the EU integration process to accelerate reforms. Now - according to the Index - Romania scores highest when it comes to public policies and legal framework, but still hosts the greatest number of institutionalised children in the region.

Armenia and Moldavia follow closely behind. At the other end of the spectrum, the Index results show that of all countries surveyed, Kosovo has parents who are least likely to abandon their children.

Meanwhile, in Romania today, a baby is abandoned in a maternity hospital every six hours.

What does the tiny decrease in infant abandonment say about child protection efforts over the last twenty-five years?

“This says that one cannot change the mentality of the public by responding to EU pressure alone,” says Penner-Hall.

“It’s been said that the year Romania joined the European Union marked the burial of [child protection] reform. With no external pressure, nothing remarkable happened. However, I believe that after 2007 smaller, more meaningful things occurred. The worst day ever was the first day of democracy in Romania; it was that day when the public conscience started to blossom.”

Guth also believes that the Index can also be seen as an X-ray of regional mentalities.

“For instance, the results prove that in Armenia 97 per cent of disabled children are taken care of by the state, while only three per cent grow in real families,” adds Guth.

“The Index also shows that in Georgia the exploitation of children through labour is not considered an issue. They think it is normal for some children not to go to school.”

Romania: number of kids in rural areas going hungry “doubled”

Back in the conference hall, Guth cautions that the results he is about to present are not part of a competition.

But he knows that the moment he opens the diagrams comparing the nine countries, the Romanians will look at where the Bulgarians stand, the Albanians will check Serbia’s scores and the Armenians will want to know if they have outrun the Georgians.

According to overall Index country scores, Romania is placed highest, followed by Bulgaria and Serbia. At a continental level, Romania has some of the most efficient child protection legislation. “The law is built upon the structure of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child,” says Guth. “In theory, Romania rocks.”

But in practice, the Eurostat data shows is that, as of 2013, the child poverty rate in Romania exceeded 48.5 per cent.

A 2014 World Vision report stated that eight from 100 children in Romania face extreme poverty, living on less than 3.5 Euro per day. The same study testifies that one out of eight children in rural areas go to bed hungry.

This percentage doubled between 2012 and 2014.

“There is so much more to do for the children of Romania,” says Daniela Buzducea, Executive Director of World Vision Romania. “Then again, to see how far you’ve come, you need to know where we started from.”

Daniela is part of the first “free” generation of social workers in Romania. Only in 1994 did Post-Communist Romania have its first graduate promotion in this field. Before this moment, this occupation did not exist.

In the 90s found Daniela in the homes of some of Romania’s most vulnerable children. She was trying, on her own, to prevent the separation of children from their families.

“To me, the Romania of those years is HIV positive children who got infected in hospitals,” she recounts.

In the late 1980s, thousands of children in Romanian institutions contracted HIV due to blood transfusions from syringes infected with the virus.

“The real moment the reform started is encompassed in a scene when I was visiting a young mum with an infected baby," says Daniela. "She had no form of support whatsoever. She was going through hell. I also had a small baby at home, and apart from visiting this woman just to reassure her that she was not completely alone, there was not much else I could do.

“One day, she was diagnosed with cancer and lost her hair because of the treatment. When I went to see her, on the wall of her house was written the word: ‘AIDS’. She had locked herself inside. She could not even take her child to the hospital because people would throw stones at them. In reforming its social protection system, this is the point from which Romania started.”

“If I had not been there, the kid would have been lost”

Albanian Zini Kore represents the national child rights network “All Together Against Child Trafficking” (BKTF). For almost twenty years Zini earned respect on the streets of his country's capital Tirana. Not just with the homeless kids, but also with the cops.

“When the Police find a new child on the street, they call me first, to pick him up and only after that do they contact the authorities,” says Zini.

Kids know they may not have much in this life, but at least there is someone fighting on their behalf until the end, no matter what kind of end that may be.

Zini never drives. No matter where duty calls, he always crosses town on foot, searching through the labyrinthine streets, scanning for homeless children.

There was a time when his phone rang incessantly - at day and night. The terrified voice of a street child on the line. No one knows the magical and subterranean paths his phone number travels to reach the kids in the city who need him most. He always grabbed his clothes and left.

“Had I not been there the exact moment the Police accosted a child,” he says, “the kid would have been lost in the inferno of the correctional institutions. From there, there is no way out.”

Today, his phone rings less often. Thanks in part to Zini and his organisation, who work hard to compensate for the state’s lack of involvement, the lives of street children have improved. But the underlying problems persist. The Child Protection Index shows that only Bosnia surpasses Albania when it comes to neglecting the situation of street children. It also demonstrates that the region has a major problem regarding the involvement of authorities in effective protection solutions.

When asked about his kids, Zini proudly mentions his boy, who is still not legally his son. He will soon turn 18 and then Zini will start the adoption procedures. It’s easier this way because at this age the young man can make his own decisions. He is one of those street children Zini fought for.

Child Protection “Mall” in Sofia

George “Joro” Bogdanov doesn’t talk much and when he does he fishes for the right words in English.

He is not a born public speaker. But he is a man of big ideas. He succeeded in putting child protection on the public agenda with an annual gala event where The National Network for Children in Bulgaria recognize citizens whose work improved Bulgarian children’s rights and prosperity and awarded them with the statue of a Golden Apple.

Now he has a new vision: The Children’s House in Sofia. This will be something like a child protection “mall” with conference and meeting rooms for child protection events and workshops; offices for the coalition’s NGOs; playgrounds for children and an educational centre for children with special needs; accommodation and a restaurant for international and local guests. Following a social enterprise model, he wants to hire disadvantaged young people to run the place.

Everybody has told him that he was crazy to even think he could raise the huge amount of money necessary to carry out his idea, but Joro went ahead and did it anyway.

He is now building the House.

“How am I supposed to feed a teenager with one Euro a day?”

Among the group gathered in Belgrade, Moldovan Mariana Ianachevici’s laughter is the loudest. It’s contagious, the kind of laughter you want to cling to in the midst of a large and unfamiliar gathering.

If one can still laugh like that after twenty-five years of helping victims of trafficking and abuse, and if one can still talk about taking home the last ten unwanted teenagers from a closed orphanage in Chisinau, there must be a parallel world better than the statistics suggest.

Mariana Ianachevici is a three-time President - she is President of ChildPact, the President of the Child Protection NGOs Federation in the Republic of Moldova, as well as the President of her own NGO, which has assisted more than 1,200 children over twenty years.

“The future President of the country,” she laughs, before relating stories about surviving the winter with canned vegetables and frozen fruits harvested from her NGO centre’s tiny orchard.

“How am I supposed to feed a teenager with one Euro a day? This is all the state gives me. When they sit down… these youngsters are so hungry they would even eat the corner of the table!”

And the story continues, about Valentina, the Centre’s long-time accountant, who never comes to work without a homemade cookie. Just to have something nice to give the kids.

About another lady, Rodica, an older employee of the center, diagnosed at infancy with polio and brain paralysis, of whom all the children are so fond, because she hands out gifts of pretzels, nuts and kind words.

“If only every child had an adult to protect them”

Daniela Gheorghe is executive director of the Federation of NGOs for the Child (FONPC). Blonde, tiny and delicate, Gheorghe wrote history by strengthening the role of civil society in Romania. Her eyes brighten when she adds that “in all these years, we mostly fought the Government.”

Her mission has been to forbid the institutionalisation of children under three years old, and she now hopes to increase this age to six.

The Index shows that institutions taking on children under two years old occurs most often in orphanages in Bulgaria, while the countries most protective of this age group are Kosovo, Georgia and Serbia.

Gheorghe earned her psychology degree in the nineties when the humanitarian convoys opened the doors of the Romanian orphanages.

She enrolled in salvation missions, and was part of the first teams to work with abused children in orphanages. At that time, she had no idea she was joining a battle that would change her life.

“After five years, I fell into a depression that would last for six months,” Gheorghe recalls. “I couldn’t distinguish colors anymore, I was seeing only black and white.”

She was representing abused children in lawsuits with the aggressors and, during her last trial, Gheorghe experienced a miscarriage. She was never able to have another child.

Nevertheless, she developed a bond with three of the girls whose own trauma of abuse she helped overcome, and today she considers them her daughters.

“I am not a mum, but I am some sort of a granny,” she says, as she flicks though pictures of the beautiful girls on her Facebook page.

One of them is a hairstylist and has two children of her own, another is studying physical therapy and the third is working with children diagnosed with autism.

Gheorghe has found joy in seeing the girls develop into independent women.

“It’s no big deal,” she says. “I just fought for them. If every child had an adult to protect him or her, we would change the world.”

Follow us