German Karate teacher recruits Romanian kids into global child abuse imagery ring

In the fall of 2001, 23 year-old Markus Rudolph Roth arrived in north Romania’s Satu Mare, a gritty town of crumbling facades, collapsing red-clay roofs and gutted industrial buildings.

He was taking up a job in business administration by a German-owned company that made furniture in the region.

But he had a side passion - giving poor kids the chance to learn martial arts for free.

One afternoon, he passed through the tree-lined entrance to the town’s German-speaking Johan Ettinger school.

There he asked the school’s principal if he could teach karate to the students.

“He was very polite,” says principal Maria Reiz, sitting in the same office where she met Roth. “He volunteered to help and took a lot of time to convince people.”

Handing out flyers and business cards attracting kids to his self-defense workshops, he went further to convince the principal to take him on - offering to buy the school a photocopier if she hired him.

Reiz decided against allowing him to teach at the school.

“I had a hunch,” she says. “My child was in the first grade at the time - and I wouldn’t even consider it.”

But Roth moved on.

Outside the town, he started teaching in a rural primary school - and then his pupil numbers boomed.

Soon Roth was coaching 200 young boys from schools across the region’s towns and villages.

“He was charming,” says Tamara Volcovinschi, principal of the ‘Ion Creanga’ school in Satu Mare. “We hung a banner in front of the school advertising his lessons.”

In 2003, he traveled to the town of Seini, a pastoral farming area where families invite strangers inside their modest homes with warm handshakes and friendly banter.

Roth, described by parents as “a good talker,” embraced this openness. It helped him give more boys the chance to take up his lessons. He also spent time visiting the boys’ parents. Over late-nights around their dinner tables, Roth would speak of their sons’ physical and emotional development, offering support and advice.

“He was a good psychologist,” says Georgiana, the mother of one of Roth’s recruits. “He understood your needs. We had trust in him.”

Roth would take the boys on minibreaks to other cities for karate tournaments or on holiday — travel almost none of the kids could afford.

“He was playing a kind of Robin Hood in our village,” says Maria, a cosmetician and strip club waitress whose son Cristi was — and remains — one of Roth’s closest followers.

To the boys, Roth was a benevolent figure who provided them with free ice cream, soda, pizza and trips to shopping malls.

Most boys we spoke to said they felt special being inside his circle.

“Some of the boys spent years with me, came each weekend to me and stayed over,” Roth says. “They felt more family with me and our group than at home.”

Dan, the father of a muscular teen named Rares, recalls the German attending the boy’s 14th birthday party in 2009.

The party was recorded that day on Dan's video camera. But later, the family noticed all recordings in which Roth appeared had vanished.

Their son remembers seeing Roth playing with their camera at the end of the night.

“He always told the kids not to take pictures with him. Ever,” says Dan.

Exposed in the pool

It was autumn 2009. In a close-knit rural community of winding roads, fields and dirt-tracks, when Andrei, a father of a 14 year-old boy, was the first to discover what was happening.

The tip came in a phone call from his cousin, a shepherd, who was tending his flock in a field behind the village.

He heard some screaming and splashing noises from a house and decided to look over the fence to see what was happening.

At first, Andrei didn’t understand what his cousin was telling him.

His teenage son and other village boys were being filmed naked in a backyard swimming pool.

Holding the camera was the polite German karate teacher.

The first to arrive at the house was another father, Liviu, who lived a few doors away. He received a frantic call from Andrei, who was running through the dirt roads of the villages to find his son.

Roth and the boys had been shooting for 90 minutes when one of his entourage - who Roth had posted as a “security guard” - warned that an adult was coming.

The two men reached the backyard and ripped down the fence around the pool.

They saw seven boys quickly dressing. Roth was holding the boys’ underwear and a camera.

He dropped everything and jumped into his car. The two fathers tried leaping on top of the vehicle to stop him.

“I chased him through the fields but he got away,” says Liviu.

Roth says he was called by a police officer a few hours later, but only had a “calm and friendly” chat.

Roth skipped town. But he did not go far.

Unknown idols

Later families discovered their sons had become unwitting child stars in hundreds of films viewed by tens of thousands of men around the world — a network of exploitation and abuse supplied out of a sprawling Toronto warehouse.

Some of these poor Romanian boys had the status of matinee idols to viewers in more than 90 countries.

Roth had arrived in Romania after serving prison time in his native Germany on a child sex abuse conviction involving young victims he recruited through karate.

A conviction of which no one in Romania was aware.

With the boys living in Satu Mare county, he took matters further.

He made and sold dozens of films featuring boys as young as eight years old posed naked in ways that a Romanian court ruled in 2010 were “explicit,” “obscene” and amounted to child pornography.

Those films are key evidence in a child pornography investigation of internationally-distributed films. Detectives in Toronto say this is the largest child pornography ring they have ever seen, with 348 arrests made across 90 countries.

They allege the website was operated by a Toronto entrepreneur named Brian Way.

After sifting through hundreds of hours of films, Toronto police charged Way, who is in custody, for child pornography.

Way, through his lawyer in Toronto, declined to comment.

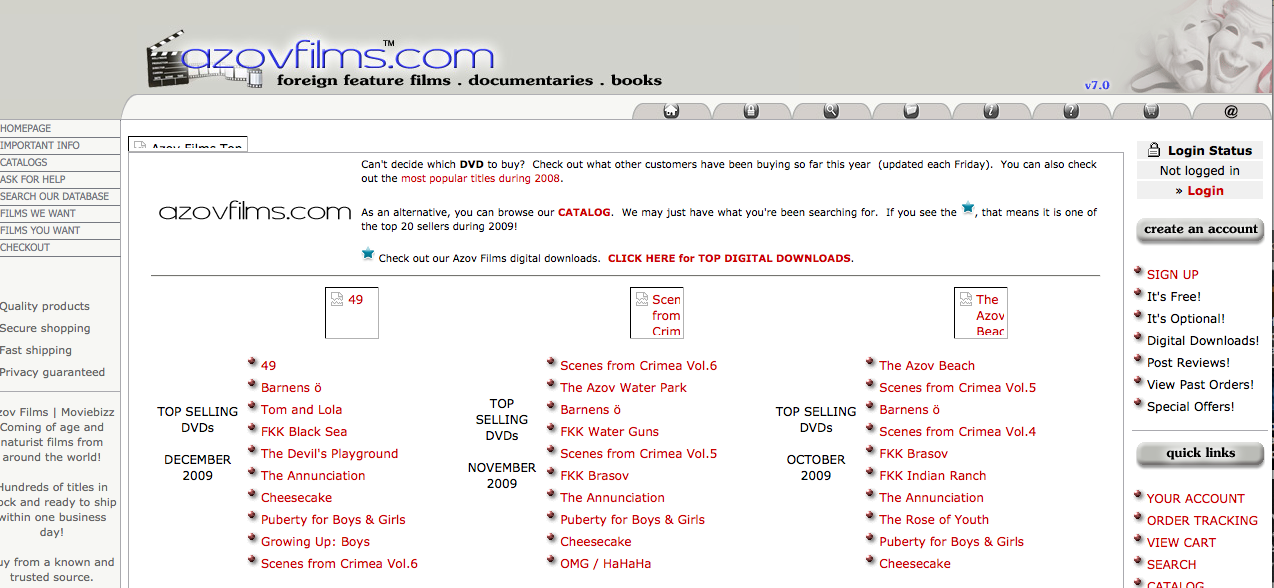

Hundreds of customers are facing – or have answered to – charges related to purchasing films from a website called Azovfilms.com. Thousands more are under investigation or facing charges.

While Roth’s whereabouts are unknown even to Romanian police (he is thought to be in Germany), during the research trip in Romania, the Toronto Star reached him through email and telephone interviews during which he confessed his regret for abusing the boys’ trust.

However he insisted he had committed no sexual abuse in making what he calls “naturist” films.

“What I did was very wrong and it hurt the boys a lot,” Roth says. “The boys get older and realize there are nude pictures of them in the Internet, they feel shame in front of their parents, family and everybody who knows…My regret is fully in my heart.”

Late developer

For six years, between 2001 and 2007, Roth claims he didn’t film the boys he was training.

But when the factory where he was working closed in 2007, he needed a new source of cash.

He began to post videos of his karate students in 2007 to a website titled “funfightkids.com.” which earned him between 1,000 and 2,000 Euro a month, according to the Romanian indictment.

Shortly after, Roth says he received an email from Canada asking him if he would film for a website called Azovfilms.com.

“I began to see it as a solution to how I can stay in the country and stay with the boys,” Roth says.

At first, the films featured the boys in their underwear.

But as trust grew and economic opportunity for Roth increased, he says he was offered more money for films featuring the boys nude.

Andrei’s son Emil, now 17, but only 13 at the time of filming, says Roth paid him the equivalent of six USD to film in his underpants - but doubled the amount once he agreed to undress.

“He asked me, ‘Don’t you want to make more money? If you get naked you’ll make more.”

Emil says he agreed because: “I didn’t know he was selling them. He told me the movies went to his sister in Germany because she likes to watch them.”

In an email Roth sent to his Canadian business partner, obtained by the Toronto Star, he writes of the sales success of a film called Winter Play -thanks to one of the boys having an erection.

“(The boy) has all the weekend long an erection if he is with us, so if you like you can get each week a top seller from me J.”

Customers could purchase the videos for 24.95 USD each. As a further “stimulus package,” customers would receive 1,100 “HUGE, super high-resolution” photos taken during the filming for 20 USD.

Roth does not believe the films were pornographic.

“My movies are not classical child porn because there was no real or simulated sexual interaction or behavior,” he says. “There was no pressure, no weapons behind the cameras.”

Det.-Const. Lisa Belanger, a veteran child pornography investigator with the Toronto Police, spent six months reviewing the cache of films seized after his arrest.

She says Roth’s movies were among the most popular and explicit on the website.

“These boys looked very young, no pubic hair, dancing around the room, showering, wrestling, karate, doing push-ups and some included a focus on genitals with full erections.”

Satu Mare abuse factory

For three years from 2007 to 2010, Roth kept churning out the videos, while deflecting suspicions and doubts from the families.

Roth insists he wasn’t worried “for a single second” that the boys would expose him.

“We joked together about how we would all be killed by the parents if they knew,” he says. “And I was right. It wasn't the boys who delivered me to the authorities.”

In police interviews, one boy said Roth routinely placed a teen at an “observation point” during filming sessions to alert him if anyone was coming.

“Roth taught us that in the event of his arrest by police to deny everything,” says one boy.

In the end, Roth tripped up on his own ambition.

A 2009 advertisement on Azovfilms foreshadowed for fans what was to come: “Construction is underway on a massive farm and soon you'll be seeing some good old-fashioned outdoor naturist activities with these boys,” it reads.

Roth, helped by the boys, built a playground in the backyard of Maria and Cristi, his closest supporters in the village, including a swimming pool. He recruited local firemen to fill it with water.

The pool remains behind the family’s spartan home, surrounded by overgrown weeds and tall grass - a reminder of the day Roth’s secret began to unravel.

After being caught by the police and released, Roth moved into an apartment in the nearby city of Zalau. His flat is within a short walking distance from a school where he again succeeded in recruiting and training new boys.

He continued production for another 10 months until 16 August 2010, when police pulled over Roth’s car with four boys inside – including Cristi, his cousin and Emil – heading for Germany.

Roth had been under police surveillance after they received a tip about him hanging around schools trying to recruit young boys into his karate classes, says Inspector Daniel Puscas, the lead investigator.

“We found out about the scandal about parents trying to beat him up in the village,” he says. “We got word it was something related to shooting some films.”

At the time, they had no information about any link to a Canadian website selling the videos. But the police felt they had to stop Roth from going to Germany.

They found plenty of evidence in the car, including high-tech video gear, tapes and recording devices.

Roth remained calm and co-operative throughout.

“If you sit down and talk to Markus Roth, in ten minutes he’ll convince you of anything,” Puscas adds. “He has a way to talk very calmly, never raising his voice, very convinced of his arguments.”

A police video taken during the raid on Roth’s apartment in Zalau reveals hundreds of tapes, wigs and toy swords and shields and a tube of lubricant.

Roth says he didn’t want to fight the police and the prosecutor, so admitted to the allegations of child pornography. This confession helped reduce his sentence to two years.

He was released from prison in August 2012.

Childhood transformed

Emil’s parents say their boy has changed - that he is now uncommunicative, dour and resigned to a quiet life away from others. He has dropped out of high school and is working on a nearby farm.

“The whole community was looking at us and pointing the finger,” says his father Andrei.

Other families courted by Roth speak of the same lingering sense of humiliation.

A boy named Mihai, only 12 when filmed by Roth, also suffers from anxiety, his parents say.

“We couldn’t afford to go back and forth to Satu Mare where the treatment is,” says his mother Claudia.

Sitting on a threadbare couch in a ramshackle farmhouse, 18-year-old Victor stays beside his parents as he explains the disgrace he and his friends felt when they discovered naked images of themselves had been sold around the world.

“We had had no idea. I feel very embarrassed,” says the teen who was 15 when he spent weekends at Roth’s apartment. “I was very ashamed in front of the community and friends.”

Despite being a convicted sex offender, Roth had access to more than a dozen schools in Satu Mare and Salaj counties - where no one undertook background checks on him. Nobody checked the exact number of schools.

After he was again convicted in a Romanian Court, there was no investigation into how the local education system allowed this to happen and who is responsable.

Meanwhile the Child protection agency says if a school doesn’t ask them for an investigation, they can’t do anything.

Plus if a Court did not order Roth to keep away from contacting the boys, he was free to do so after his release. Which he did.

Since the incidents, very few of the children have had comprehensive therapy or psychological assistance.

This is despite the harrowing process of the police investigation, prosecutorial probe and court hearings.

Parents accuse the prosecution of verbally abusing the children and shouting at them to recognize whether what they suffered was sexual abuse.

They were also told not to ask for any financial compensation in Court.

Defending the abuser

Most of the parents and kids are angry at Roth - but one boy has another view.

Cristi became a well-known draw on the Canadian website, receiving top billing and a steady following.

“I have no anger towards (Roth),” says the now 18-year-old sitting at his family’s dining room table. “It was not such a big deal as everyone made out.”

In one high corner of the room, a statue of the Virgin Mary looks down. Around Cristi’s neck hangs a large crucifix. On the table before him lies a collection of his karate medals.

Roth is the closest to a father Cristi has ever known, say villagers, police, his mother Maria and Roth himself. Roth was presenting Cristi as his son to parents of kids he tried to recruit.

“(Cristi) found trust in me,” says Roth, who says he is estranged from a son he fathered in Germany. “I feel after so many years responsibility, (maybe) it's a kind of compensation for other responsibilities which I didn't take…In my mind Cristi was, is, and always will be my son.”

Maria trusted Roth with her son when they met nearly a decade ago.

He bought Cristi karate outfits and took him on trips, training him for free and providing a strong male presence.

“He came so close to us and I couldn’t understand why he would befriend this poor family,” she says. “My impression was that because he had a boy Cristi’s age, he was trying to replace his loss.”

She now struggles for a metaphor to describe the impact Roth had on Cristi.

“A nuclear bomb,” she finally says. “Hiroshima. He’s a totally different boy. He used to be a very good student. He wanted to prove he could make it being from a poor family. He doesn’t have that ambition anymore.”

Some have called Cristi “gay”, she says, which has come with threats of violence in a place where homophobia is widespread. She and Cristi left the village for a long time after the arrest.

Most villagers acknowledge they have shunned Cristi and Maria for bringing Roth into their lives.

Now Roth says he leads a quiet life in business administration and says he volunteers helping an elderly man once a week.

He uses the alias “Florian Berger” in emails and refuses to say where he lives.

“I think about (what happened) every day,” he says. “My hope is that the boys get what they deserve in life. I hope they find happiness… And if a few of them find a way to forgive me sometime, I will die one day much more quietly.”

A version of this story appears in the Toronto Star by Robert Cribb. Stefan Candea contributed with investigating this case in Romania.

* Names of boys and their parents were changed. Names of the small villages were left out of the story.

Follow us