Football Leaks: The Argentine Connection

Anyone who wants to bring a bouquet of flowers or a tax form to top Argentine football player Javier Pastore has to go to the central Dam square in Amsterdam.

There, right across from the Royal Palace, is the office of his agent.

Until the end of November, there was a mailbox with a lock attached behind the front door of the office building. Every night a shady figure came to collect its contents.

Now, on a sunny December day, the mailbox of Pastore and many other South American football stars is gone.

Only four drill holes are left. The manager of the building got so fed up with the bailiffs and the delivery of dozens of letters and demand notes, that she removed the mailbox.

Pastore’s agent was not the only one who registered the Dam as a visiting address with the Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce and the tax agency. Dozens of other companies – from car traders to constructors – and hazy foundations have their seats in this building, without its manager’s approval.

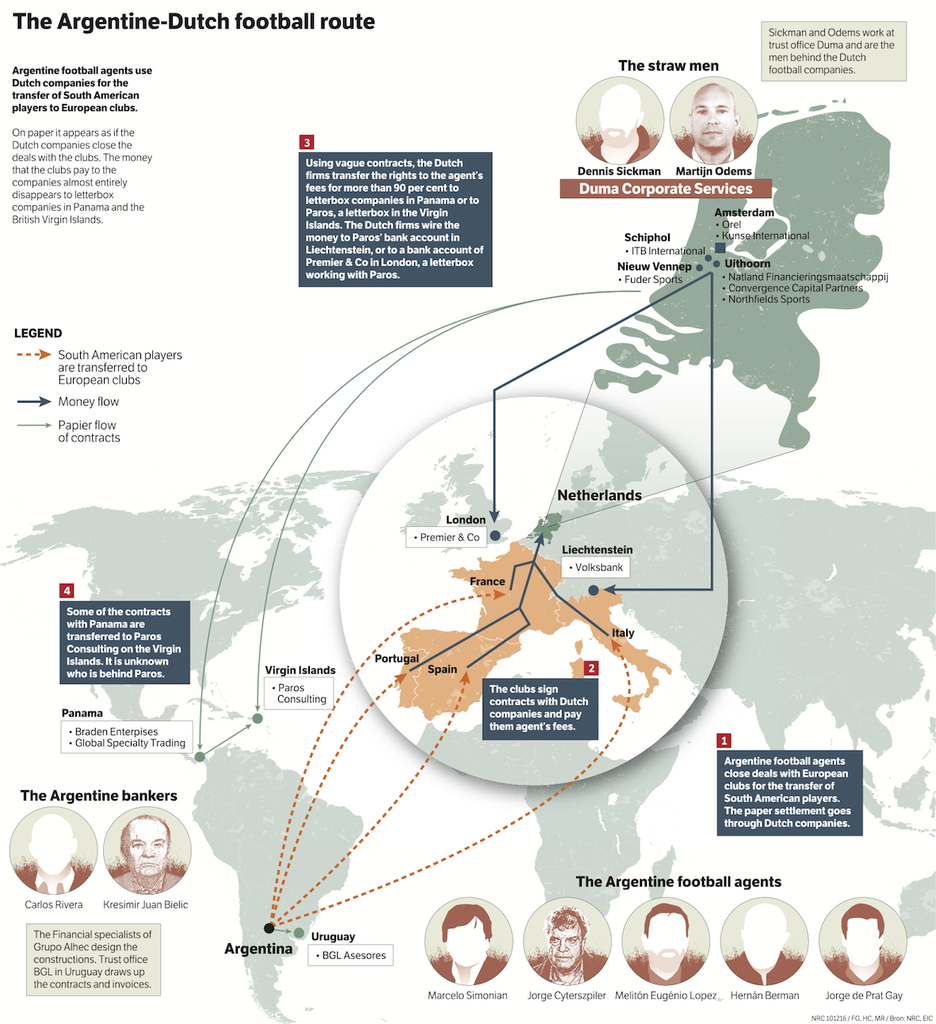

It is no coincidence that South American transfers are settled via the Dam. Amsterdam is an ideal stop-over for global money. The Netherlands has a good reputation when it comes to international money transfers, and the supple tax agreements that have been made with nearly every country.

When it comes to football, the famed Dutch transparency exists mainly on paper, as NRC and the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network discovered. The football companies in Amsterdam and further afield fulfil all their obligations, file their annual accounts and have a postal address.

But whoever tries to get in real contact with these companies, encounters a web of fabrications.

Perfect straw men

One of the firms registered at the Dam is football agency Orel BV. Alongside eleven similar companies, it turns up frequently in Football Leaks, the trove of 18.6 million documents from the football world that NRC and EIC have investigated in the last months.

At first sight, Orel’s director Martijn Odems (38) is a successful player agent, with a license from the Dutch football association KNVB. He is accompanied by his direct boss, fiscal lawyer Dennis Sickman (44). They seem to be the big men behind dozens of transfers of South American football stars like Pastore, Radamel Falcão, James Rodríguez and Angel di Maria to big clubs in Spain, Portugal, Italy and France.

In reality, Odems and Sickman are the perfect straw men for player agents from Argentina. Those agents want to pay as few taxes as possible from the millions they make with the transfers, and use The Netherlands as a pivot. They are assisted by Grupo Alhec, a company that is controversial in South America. It is known as ‘the financier of Argentine football’.

Odems is never in the building at the Dam. He does not pick up the phone and does not answer voicemails and emails from NRC. Neither can he be found at his home in Nieuw Vennep, a small town near Amsterdam.

At this address, a standard terraced house with parking bays and saplings outside, one could theoretically find Jorge Cyterszpiler, one of the most colourful figures in Argentine football. The childhood friend and former agent of Diego Maradona is one of the directors of another sports agency, based in this house in Nieuw Vennep.

The other director is Sickman, for whom this is no more than a job on the side. Sickman’s main occupation is being director of Duma Corporate Services, a trust office at the Zuidas (Amsterdam’s financial district) that holds dozens of companies. Martijn Odems works there as a legal advisor.

The two men are directly or indirectly involved in most of at least twelve letterbox firms, registered at home addresses or in business complexes in the small towns Nieuw Vennep and Uithoorn, or in Amsterdam. They all have nondescript names like Orel BV. The BVs tend to be controlled by men whose job is not to stand out.

At first glance, the Dutch football BVs appear to operate independently: they regularly change management and move from one address to another in Noord-Holland province. But in reality, the companies are intertwined, and Sickman's trust office Duma Corporate Services plays a central role – as revealed by research carried out by NRC.

Odems' name was mentioned previously. In 2013, NRC described how he showed up in the annual reports of FC Porto as a recipient of large sums for arranging the transfer of top striker Radamel Falcão to Atlético Madrid.

Early this year, Football Leaks published confidential documents which showed that a company owned by Odems was diverting money from player transfers in Italy's Serie A to Panama.

“Much of the money we pay for football disappears into agents’ pockets”

There is a “dark net of football money”, says Antoine Duval, a researcher at the Asser International Sports Law Center in The Hague. “It is a parallel world of money flows. Much of the money we all pay to watch football disappears into the pockets of agents. They do their best to minimise the tax they pay and maximise the money that goes into their secret bank accounts.”

Avoiding transparency is an important part of that, says Duval. “They make the chain so long that very few people can follow it, particularly because they jump from one jurisdiction to another. You see plenty of this kind of thing in the business world, and football is not immune. Football, particularly the transfer market, has become a huge financial industry.”

Trust offices provide foreign companies and their subsidiaries with a location in the Netherlands, which they often manage on behalf of the owners. The Dutch central bank DNB requires that they comply with strict rules. For instance, they must know the origin and destination of the money which flows through the companies they manage and make certain that they are doing business with bona fide parties.

Illustrative of Duma's working method in the football world is the story of writer and poet Marco Termes, who was the director of two of these football BVs between 2009 and 2014. Termes was employed by Duma. His work involved opening the mail on behalf of the trust office for one football BV and a number of other specially established companies registered to the address of his council apartment in the coastal town of Zandvoort.

A few times a year he had to travel abroad to get football contracts signed in south Europe. The trust office provided the airline tickets and a good mid-range hotel for him and gave him the contracts to be signed. He was trusted and spoke a number of languages. Termes read all the contracts carefully, because he didn't want to get involved in anything illegal.

Because it was the perfect part-time job for him alongside writing novels and poems, Marco Termes asked few questions. At the end of 2013, his job at the trust office was suddenly terminated. The chain of football limited companies had to be rerouted, and Termes and his Zandvoort address were no longer required.

Amsterdam: where accounting is a shadow game

Termes’ account is supported by e-mails and contracts in the possession of this newspaper. They provide a fascinating glimpse of the shadow accounting kept along Amsterdam's Zuidas of dozens of transfers and deals relating to Argentine, Colombian and other South American football players.

The documents reveal that all these players are paid for in Amsterdam, by men who - as far as the outside world and football fans are concerned - frequently have nothing to do with the clubs or players, but who still claim their share of the profit.

The game is played with a range of income sources: millions from image rights contracts with the sports company Nike, agency fees, investments in the economic rights of players and scouting contracts.

Football Leaks, which contains only part of these shadow accounts, shows that at least 30 million Euro of football money have flowed through The Netherlands to The Caribbean in the last years.

International transactions that would be highly unusual in The Netherlands, are smoothed over at the Zuidas. For instance last year, when Jorge Cyterszpiler received a cash payment of 125,000 euro by Grupo Alhec, somewhere in South America. The contracts were signed in the Uruguayan capital Montevideo, but the transaction was settled through Cyterszpiler’s Dutch company in Nieuw Vennep – 11,000 kilometres away.

The paperwork put together along the Zuidas has an amateurish look to it. Contracts dividing up millions look as if they have been picked up off the Internet and are full of vague descriptions. They generally refer to the performance of “certain services” relating to football transfers. Those services are barely described, if at all, but they are remunerated very well.

There is also a continual alternation of companies, and contracts pass from firms in The Netherlands to the tax havens Panama and the British Virgin Islands. Another striking feature are deals involving players switching to new clubs on paper but never actually playing there. This is a bogus arrangement designed to evade tax, which is well-known in South America.

The Dutch tax authorities have been looking at the straw men’s work for some time now. There are millions flowing through these companies while they do not seem to actually do anything for the money. But evidence of money laundering has not been found so far.

Money flows from company in money-laundering probe

The Football Leaks reveal that the Dutch money flows are a one-two between Duma Corporate Services in Amsterdam and a controversial firm based in the Argentine capital Buenos Aires: Grupo Alhec, an investment company, bureau de change and bank.

Alhec has a bad reputation in South America: in 2013, a Panamanian subsidiary of the group was closed down due to suspicions of money laundering related to football transfers between Argentina and Europe. In the same year, Alhec was the focus of a large-scale money-laundering investigation by the Argentine authorities. This was a major operation, involving 150 raids on football clubs, players' agents, the Argentine FA, Alhec and even the Argentine central bank.

The suspicion was that European clubs were paying more for players and agency fees than was shown in the invoices, and that the surplus was reaching the Argentines tax-free via complicated routes, including the Netherlands. As part of the investigation, a telephone call between Cyterszpiler and Carlos Rivera, one of the owners of Alhec, was tapped. In that conversation, which was broadcast on Argentine television, Rivera suggested to Cyterszpiler to persuade a player in Argentina to engage in match fixing.

Neither Alhec, Cyterszpiler or anyone else has been prosecuted to date. A court ruled that the judicial investigation had not been conducted with due care and replaced the examining magistrate. According to Argentine media, the new examining magistrate is currently investigating over 400 football transfers.

Cyterszpiler is not the only players' agent making use of the Dutch route. At least four other well-known Argentine agents are doing the same, in most cases in partnership with Alhec. The most prominent among them is Marcelo Simonian, one of the biggest agents in South America, who represents players like Pastore and Falcão. His partnership with Alhec is highly intensive, the documents reveal.

In an e-mail exchange with Alhec chief Rivera, one of the other agents makes clear that tax avoidance is the prime reason for using a Dutch private limited company. Initially he is still undecided as to whether to choose a route via the Netherlands or Spain. Then, opting for the Netherlands, he writes: “As long as no tax is levied, it's fine.”

"British Virgin Islands offers more discretion than Panama"

Until mid-2013, the payments via the Netherlands took place reasonably openly, but immediately after the actions by the Argentine judicial authorities, Alhec decided to henceforth operate under the radar. The details show that following the raids, Alhec switched to a trust office in Uruguay which has since been involved in all its business.

This office, BGL Asesores, takes care of the paperwork. Correspondence about the football business routed through Dutch BVs has since been conducted by hushmail, a secure e-mail program that is hard for law enforcement authorities to crack. Those involved no longer refer to each other by name in the e-mails but instead use aliases, abbreviations and numbers.

Most of the constructions using the Netherlands are devised in Buenos Aires or Montevideo and effectuated in Amsterdam. The main language is Spanish and the millions of euros in profits end up with companies in Panama or, since 2013, the British Virgin Islands. There, a company called Paros Consulting is used, that now functions as a treasure chamber.

The discretion which the Virgin Islands offer companies is even greater than in Panama. In both countries, companies do not need to submit annual accounts and shareholders can remain secret. However, on the Virgin Islands the directors also remain anonymous.

Who owns Paros is unclear. But Rivera does refer to Paros as “my company” in an e-mail. And in the e-mail exchanges with BGL and others, he takes crucial decisions on Paros. Football Leaks do not contain decisive evidence, but it is highly likely that agents like Simonian ultimately get their money from Paros after all the intermediate steps.

Why all the detours? Why for instance does FC Porto, that works with Simonian intensively, not transfer the agent's fee directly to Argentina?

“Don’t ask me to lie! I only lie to my wife!”

According to Simonian, the only one of the Argentine bankers and agents who responded to questions from this newspaper and EIC, even the slightest reference to tax evasion is a scandalous accusation.

“I am the biggest tax payer in the Argentine football world”, he shouts into the phone. “I pay all my taxes. Are you paying the bill for this phone call? I am very poor because I have to pay all these taxes!”

Simonian says he has never heard of Paros. Neither of Orel.

“Don’t ask me to lie!”, he says. “I only lie to my wife!”

In his view, Carlos Rivera is “a banker who has had a very good reputation for a very long time in Argentina.” And yes, Simonian does business with him occasionally. “Small things”, like changing money, or “some investments”.

From Portugal comes a different perspective. “Orel was the company named by Mr. Simonian for the intermediation” in the transfer of the Columbian player James Rodríguez, FC Porto says in a reaction. An e-mail from Porto in the Football Leaks also states that Simonian appointed Orel as the club’s business partner when Falcão came to Porto.

No, she has “never heard of” Dennis Sickman. And Martijn Odems? “Don’t know him”, says the receptionist of a tax advisory office on the ninth floor of a large office building on the Amsterdam Zuidas. According to contracts in the Football Leaks, the trust office Duma Corporate Services is based here. The receptionist is obviously struggling to keep a straight face. “Duma? That doesn’t ring a bell at all.”

Then a door opens behind her, and a big man enters the corridor, while the receptionist continues denying. The big man is Dennis Sickman, director of Duma and Dutch straw man-in-chief of Argentine football.

“Would you please leave the premises?”, he says in a demanding tone. He moves in front of the receptionist to show his unexpected visitors the door. “We don’t comment.”

World Cup hero James Rodríguez transfer: a textbook sleight of hand using Dutch firms

The transfer of the Colombian midfielder James Rodríguez, top scorer at the last World Cup in Brazil, is a prime example of the sleight of hand involving Dutch limited companies – designed to channel millions from Portugal, via the Netherlands, to tax havens in the Caribbean, tax-free and with no awkward questions.

In recent months, Rodríguez has been mostly warming the bench at Real Madrid, but in 2011 he arrived at FC Porto as an outstanding, 18-year old prospect from the Argentine side Banfield. In the three years he played for Porto his value increased from five to 45 million Euro, a splendid investment. Marcelo Simonian, one of the biggest player’s agents in South America, was an intermediary in Rodríguez transfer to Porto. Simonian uses Dutch letterbox firms for all contracts with European clubs.

For Rodríguez' move to Porto, a construction was set up that made it appear as if not he but the Dutch firm Orel BV had put together the deal. In the summer of 2010, a year before the transfer, Orel director Martijn Odems signed a contract for this with a company based in Panama, Braden Enterprises.

Kresimir Juan Bielic, an Argentine born in the former Yugoslavia, signed on behalf of Braden. Together with Carlos Rivera, he owns Alhec. It is a remarkable contract: Orel outsourced the negotiations with Banfield (Rodriguez' club) to Braden, which received 94 percent of the proceeds in return – nearly the entire sum paid by Porto in agents' fees. The remaining six per cent were presumably for Orel.

A year later, Braden transferred the contract with Orel to another Panamanian company: Global Specialty Trading (GST). Bielic signed this contract on behalf of both Braden and GST. Then, in November 2013, the contract with the Dutch firm Orel again changed hands: this time, Orel promised to transfer the money to Paros Consulting, based in the British Virgin Islands. Porto states it does not know the Caribbean companies.

Rodríguez had by now won a Portuguese Player of the Year award and had left for AS Monaco for a transfer fee of 45 million euro. Orel was entitled to ten per cent of the transfer money. It is unknown if Simonian is the ultimate beneficiary.

In January 2014, Orel received an invoice from Paros requiring it to transfer 4,121,185.13 Euro to Paros' bank account in Lichtenstein, for “services” in the “Porto-Orel transaction” in connection with “the football player J. Rodríguez”. In this way, Orel ultimately handed over the bulk of the earnings.

Investigation by Hanneke Chin-A-Fo, Hugo Logtenberg and Merijn Rengers at NRC Handelsblad, part of the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) Network

Follow us