Fact and fiction collide for top football clubs’ Dutch straw man

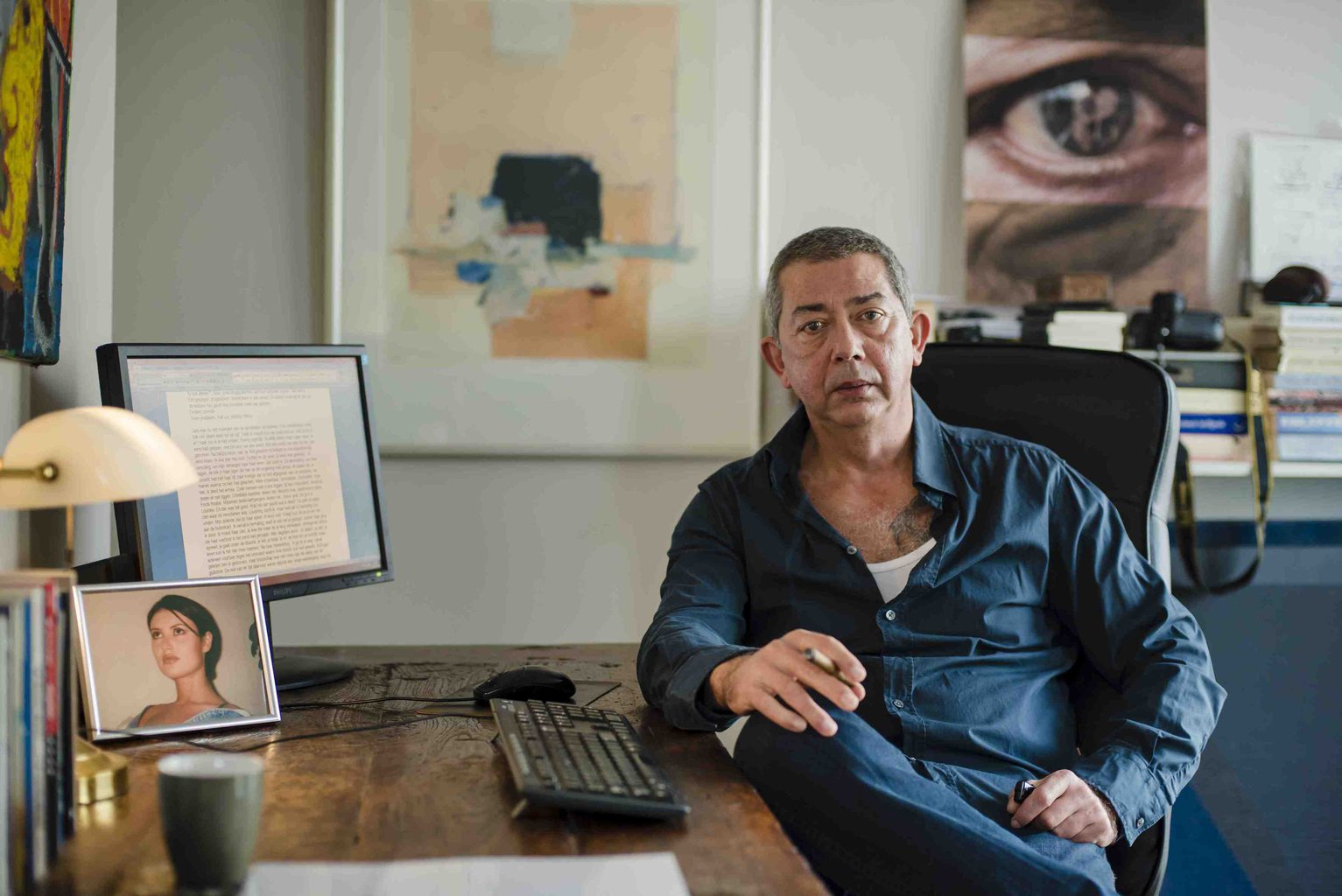

Marco Alexander Termes is “the real deal”: a real Zandvoort resident, a real tough guy, but above all: a real artist. Seven days a week, he sets the alarm, turns on the computer and continues working on his next manuscript.

“I literally write myself to into the ground,” he says. His work rate is incredible. In a couple of years, he wrote eight novels, short stories, thousands of aphorisms and three books of verse.

Termes is also a real straw man. Between 2009 and the end of 2013, his social housing apartment on Zeestraat in Zandvoort was the address of a company - Convergence Capital Partners BV - involved in international football’s top leagues (he directed a second one, based in a nearby municipality).

In 2011, this company had 30 per cent ownership on paper of the Colombian professional footballer James Rodríguez, who then played for FC Porto. Director: M.A Termes.

Not that he ever met the Columbian midfielder or watched him practise his half volleys on a training ground. But he did have dealings with the millions earned by Rodríguez.

He’s an Ajax supporter, because his father once took him to De Meer stadium in Amsterdam and he liked the creative match play of the Amsterdam team. He sometimes watches football on television, also to give him something to talk about in the beach resort, where residents have little interest in literature. But ultimately, football is a side issue, says Termes.

“Nothing really excites me, except writing. The rest is bullshit.”

“Straw man job: only ten hours a week”

At the end of 2008, a friend asked if he might be interested in a job with a trust company in Amsterdam. The job description: he’d be director of a number of companies which would be registered at his address. He would handle the post, go along to meetings if the trust company called and travel as a representative of the companies to collect signatures in south Europe.

Termes had his reasons for taking the job. In 2006, he had promised to spend the rest of his life working as a writer – but sold very few books. In order to achieve his sacred mission, the job at the trust company was ideal: he worked from home and the poet spent no more than ten hours a week on the job.

In early 2009, the first company was registered at his address, Creatermes – an “organisational consultancy” operating “in the field of media and telecommunications”. The formation expenses were paid by the trust company and the shares paid up. The Polish chocolate factories of E. Wedel, which were based in the Netherlands for tax reasons, were also registered at his address.

The footballers came soon. Through the trust, three Argentinian football talents, then aged 15, 16 and 18, authorised Termes to sell them to a football club anywhere in the world and the trust would keep the proceeds. Termes retained his salary.

“I was destined to be a writer”

Marco Termes wrote his first poems at the age of thirteen and four years later, he knew for certain: he was destined to become a writer. His parents gave him every freedom. They had a restaurant, Terminus, on the beach at Zandvoort. His father combined that job with being a councillor for the coastal municipality.

He wrote his first novel, the philosophical thriller Tyrannosaurus Regina, when he was seventeen – about the fictional character Tamara Raziani, a beautiful and intelligent banker’s daughter. Six years later, he put down his pen. He felt that the publishing world was too commercial and he was annoyed at his lack of real life experience. First he had to live a bit to “experience things to write about.”

Termes was a handsome boy - and he was fit. He modelled in fashion shows and danced at the World Disco Dancing Championships in London in 1978. He spent five years as a background dancer at the public broadcasting channel Avro. An adventure as a singer in a boy band - an idea mooted by the producers of 80s Dutch sextet Dolly Dots – went nowhere, but his contacts in the media did get him a contract as a hand model.

For fifteen years, his perfect hands adorned advertisements for beer, watches and packs of washing powder. In the meantime, he worked as a contractor, barman, petrol pump attendant, quiz question maker and caterer – until at the age of forty, he washed up in the Cypriot capital of Nicosia where he was tapped on the shoulder by a 24 year-old Russian beauty.

“Here was the woman I had written about when I was 17”

“Have you been waiting long for me?” she asked, and he knew at once: this was Tamara Raziani, the woman who had starred in his first novel – but now in real life.

“Twice in my life, my novels have crossed with my own reality,” he says. “The first time was in Nicosia. I was dumbstruck. That was the woman – the woman I’d written about as a 17 year old boy. Two hours later, I asked her to marry me.”

For six years, the writer was married to the Russian Lillia. They lived together in a tiny apartment in St Petersburg and later on Zeestraat in Zandvoort, but their love didn’t last. Lillia now lives in Amsterdam, has two young children with another man and doesn’t want any contact with Termes. But she is and will always be his muse. He turns down other women and has recently had her tattooed on his chest and leg.

“The trust instructed me to go to Lazio Roma”

The second time fact and fiction coincided was around five years later, when Termes was dispatched with another stack of football contracts. He’d collected his instructions from the trust company on the Zuidas in Amsterdam, got a plane ticket and – suited and booted – had flown to Rome. There he had to collect signatures from the board of Lazio Roma.

To his amazement, the club’s offices were in a building that had played an important role in the novel he wrote when he was 17.

“In the hall, by the door of the office of Lazio’s chairman, was a statue of the god Ajax,” says the writer. “Ajax was my club – and I asked the secretary if she could take a photo of me with the disposable camera I’d bought at the pharmacy.”

He’s kept the photo of Marco Termes, the football straw man who walked into his own debut novel. Just like the skirt that Lillian was wearing that evening in Nicosia.

“I turned from a value to a cost”

The “ideal part time job” at the trust company lasted until the end of 2013. From one day to the next, he changed from “something of value to a cost item” and his contract was terminated. The fact that Dutch football companies were being intensively investigated by the Argentinian prosecutors in that period means nothing to him.

“In my years with the trust company, I had to sign and read all the contracts and papers,” says Termes. “As far as I could see, everything was above board, but I only saw a small piece of the puzzle. It was like being in a room divided by a heavy curtain. Plans were made on one side of the curtain and I was on the other. Sometimes a piece of paper was pushed through the curtain, which I then had to do something with.”

He won’t go into more details.

“They’re all accountants, who operate in an extremely closed world. I signed a confidentiality agreement and maybe I’ve said too much already. That’s because I’m honest through and through and because the business world really doesn’t interest me.”

He’s not angry with the men who made him director of two football companies and then let him go. In fact, he is rather grateful.

“I was able to devote four years of my life to my writing and experienced things which gave me things to write about. I was a goldfish in a bowl of piranhas.”

Written by Hanneke Chin-A-Fo, Hugo Logtenberg and Merijn Rengers at NRC Handelsblad, part of the European Investigative Collaborations Network (EIC)

Follow us