When Turkish businessman Yıldırım Demirören quit as the president of Istanbul football club Beşiktaş, on 27 February 2012, he left behind a legacy of destruction. The club’s finances were in dire condition, with €200 million in debt, an accumulated budget deficit of over €160 million, and a growing pile of unpaid bills. One of the great historic Istanbul teams, alongside Fenerbahçe and Galatasaray, Beşiktaş would soon receive its second ban from the UEFA Champions League and was deeply embroiled in a match-fixing scandal.

But the outgoing chief was not resigning in disgrace. In fact, his departure was necessitated by his appointment to a better job, as head of the Turkish Football Federation (TFF), the governing body of football in the country. He still occupies this post today.

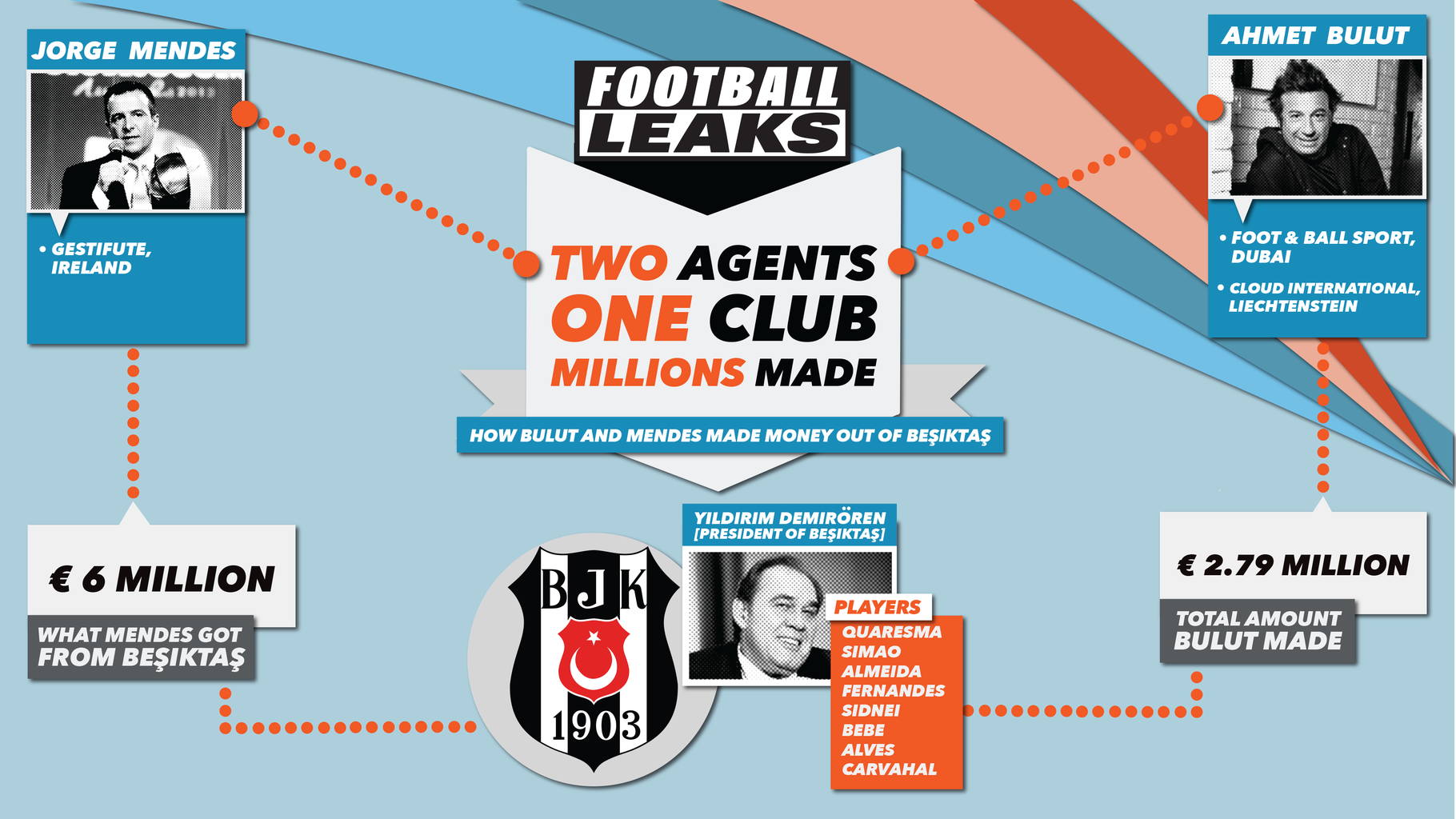

Part of Beşiktaş’s financial woes stemmed from questionable transfer deals Demirören facilitated with players connected to the Irish football agency, Gestifute, run by Portuguese agent Jorge Mendes. In little over one year, mostly in a six month period, Demirören personally signed secret commission agreements with Gestifute that netted the world’s biggest agent €6 million in fees and cost the club over €60 million in transfers and player salaries.

The new investigation by The Black Sea, based on Football Leaks documents obtained by Der Spiegel and shared with the European Investigative Collaborations journalism network, reveals that Gestifute’s lucrative commission contracts with Beşiktaş were illegitimate and broke FIFA and Turkish Football Federation rules.

The documents show that when Mendes tried to recover €1.75 million in overdue payments from Beşiktaş, his Turkish lawyer informed him that “taking the dispute to FIFA was very risky” because the association would likely reject their validity.

Three separate lawyers and a money laundering expert consulted by The Black Sea confirmed that the appearance of Gestifute and the signature of the company’s tax accountant - who is not a licensed FIFA agent - rendered them improper and illegitimate.

The deals might also have broken FIFA and TFF rules on conflict of interest, since they were each of them private commission contracts arranged directly between the club and Gestifute, which was improperly acting as a player agent in the negotiations.

Also involved is Mendes’s Turkish associate, fellow superagent Ahmet Bulut, who could also be breaching Turkish Football Federation rules by failing to declare his role as an intermediary on at least eight of Mendes’s deals.

Beşiktaş racks up debts

Before Yıldırım Demirören was involved in football, he was a powerful businessman in Turkey, known as the vice-president of the Demirören Group, an energy and construction conglomerate built by his father in the 1960s.

It is common in Turkey for rich industrialists to covet positions as heads of football clubs, valuing the prestige, visibility and social props that often accompany the role. Lawyer and professor of Sport Law at Loughborough University, in the UK, Serhat Yilmaz, told The Black Sea that these rich men come in as “saviours and inject money into the clubs. But then they often make bad deals and they have zero responsibility. If there is a financial problem, they can leave,” as Demirören did.

Demirören was president of Beşiktaş from 2004 until 2012. During his time, the club was poorly managed financially and accumulated unprecedented levels of debt. When Beşiktaş faced a financial investigation by UEFA, as part of the body’s Financial Fair Play regulations, it placed significant blame for the poor state of its bank balance on transfers and agent commissions that Demirören had conducted with the superstar agent Jorge Mendes and his Turkish sidekick, Ahmet Bulut. Deals which are now revealed to be rule-breakers.

Mendes’s and Bulut’s first business with Demirören, and each other, occurred in the summer of 2010, as the pair negotiated the €7.3 million transfer of 27-year-old right-winger Ricardo Quaresma to Beşiktaş from Inter Milan. The price tag made the Portuguese midfielder one of the most expensive signings in Turkish football history. For his efforts, Mendes earned €2 million in agent fees. The money was sent to the account of his Portuguese firm, which was a potential violation of Turkish Football Federation rules that state deals can only be conducted with a “natural person” and not a company.

“The Turkish Football Federation did not allow companies to have contracts like this [at the time],” Turkish lawyer, Mert Yasar, who has an interest in sports law, told The Black Sea, “it had to be a natural person.”

Bulut: the invisible agent

The involvement of Bulut was problematic, as he received €750,000 of the fee from Mendes for his work on Quaresma. His name, however, appears nowhere on the official documents, which, say lawyers, is a breach of Turkish Football Federation rules. “Bulut’s role had to be declared to TFF,” said Yilmaz. “He has to have a license to do these things, but that’s not enough. He had to have a representation contract.”

During the Quaresma negotiations, Bulut courted the Portuguese agent every day, even flying to a meeting at the luxurious Villamagna Hotel in Madrid. Bulut recalled the encounter as a meeting of minds: "We were friends right away,” Bulut told the Spanish authors of a book on Mendes, “and it was because we saw each other on the same level. It was all very positive from the beginning.” Their deals were all conducted he said, “without having anything signed."

Tugrul Aksar, a bank manager and expert on football finance, who co-founded the Football Economy Strategic Research Centre in Istanbul, told The Black Sea: “These kinds of deals are ‘collusive transactions’ and if authorities and other parties who are involved in the same deal would lodge complaints, the agreements could be nullified,” he said. “Federations should strictly regulate such transactions and should not allow them.”

Whatever the legal implication of such an arrangement, there was a lot of money to be made. And in Demirören it seems that Mendes and Bulut had found themselves a rain-maker. Over the course of seven months, from January to August 2011, Mendes and Bulut concluded seven more deals with Beşiktaş, always with Bulut operating behind the scenes, never appearing on any official paperwork.

In the January 2011 transfer window, the Beşiktaş president signed a bunch of Portuguese players - including leftwinger Simao Sabrosa from Atletico Madrid for €1 million and centre forward Hugo Almeida from German club Werder Bremen for €2 million. They also loaned midfielder Manuel Fernandes from Spanish club Valencia for a fee of €200,000.

Mendes earned €2.5 million for this work: €1 million for the Simao contract negotiations - €100,000 more than Atletico Madrid’s transfer fee - and €1.5 million for Almeida, according to Football Leaks data.

In the case of Almeida, Beşiktaş utilised third party ownership (TPO) investment fund Quality Football Ireland to subsidise the €2 million in return for fee handing over a 45 percent stake in the player.

Incidentally, 10 percent of Beşiktaş's 55 holding was really owned by Mendes though a secret Third Party Ownership (TPO) agreement with the club – a fact Demirören failed to disclose to the club’s shareholders. It seems that since the club paid nothing for Almeida, it was feeling generous when it came to contract negotiations, offering the player a particularly lavish employment terms that included a €2.5 million salary, business class flights, a Porsche Panamera, lease of a private jet and a choice between a BMW X5 and an Audi Q7 v12. When Almeida left the club on a free transfer two years later, Beşiktaş was forced to repay his entire transfer €2 million fee to QFI.

Ronaldo: to play for Beşiktaş?

Why Demirören so freely spent struggling Beşiktaş’s badly needed cash, or why so much of it went in Mendes’s direction, are questions the TFF President refused to answer. But after this first round of transfers, Mendes instigated a charm offensive on Demirören. And he used one of his biggest weapons: Cristiano Ronaldo.

In April 2011, Ronaldo was pictured with a starstruck Demirören in Porto Santo, Madeira. They were, they said, discussing a hotel investment on the island, worth €80 million. The hotel never materialised. But as the summer transfer window commenced, in June, Ronaldo flew to Istanbul to attend the opening ceremony of Demirören’s shopping new mall that was located in the heart of Istanbul’s protected historic centre.

The construction had been problematic for the Beşiktaş president, who had faced harsh criticism from Turkish civil society and NGOs for ignoring building regulations. The issues over Turkey’s planning laws were forgotten, however, as thousands of people and Turkey’s media flocked to Demirören’s mall to see a glimpse of the superstar Ronaldo, who proudly announced he was in attendance because “the president Demirören is a good friend”.

The Beşiktaş president basked in his new popularity. But the attention from the Ronaldo episodes sent Demirören into a frenzy and he began hinting during TV interviews that perhaps the world’s most expensive player might himself soon make a move to Beşiktaş.

Ex-Beşiktaş board member, Ibrahim Altinsay, told The Black Sea that these kinds of conflicts of interest, with Demirören seemingly using Beşiktaş’s money to help promote his private business, are normal in Turkey. “Things happened so out in the open,” he said. “They brought Ronaldo to Turkey. You wouldn’t see this at a normal club: a player represented by an agent, with whom a businessman has dealings, attending the opening of a private business.”

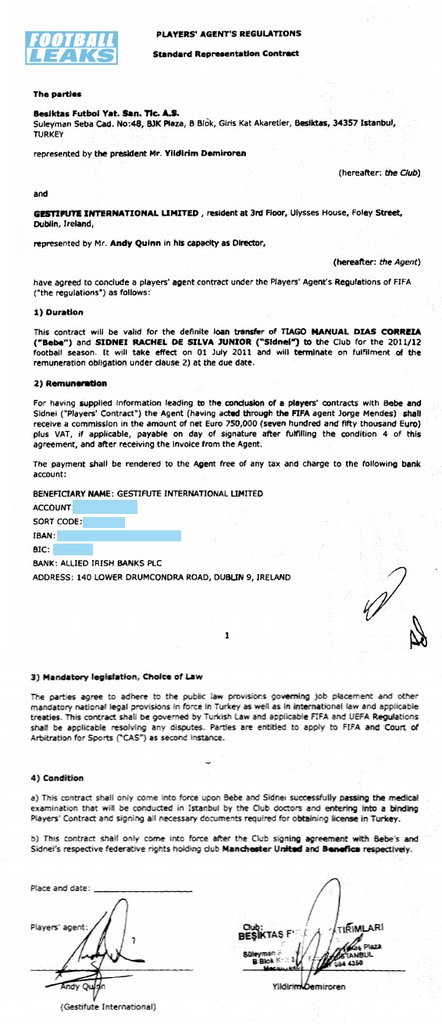

Whatever the ethics issues, the plot worked. That summer Beşiktaş would take Benfica’s Brazilian central defender Sidnei and Manchester United’s Portuguese forward Bebé – both Mendes clients - on loan for a cost of €1.2 million, with Mendes securing a €750,000 commission. The club also bought Portuguese midfielder Julio Alves for €3.1 million.

Although there is no documentation on payments of commissions to Mendes for the Manuel Fernandes loan in January, six months later, as the player made a €2 million permanent move, Mendes secured a €1 million fee. After the deal was signed, Mendes’s lawyer Osorio de Castro emailed Ahmet Bulut, who was key to securing Beşiktaş’s signature, nicknaming him “Ahmet, the magician!”

By the time the 2011 transfer window closed in August, Mendes and Bulut had shifted a total of seven players to Beşiktaş. So ostentatious was Mendes’s domination over Beşiktaş and Demirören that the Turkish sports media took to calling the influx the “Portuguese wave” and the “Portuguese Gang”, even though Sidnei is Brazilian.

That summer, Mendes and Bulut had even managed to install Portuguese player-turned-coach, Carlos Carvalhal - a Mendes client - as Beşiktaş’s temporary manager, to replace the club’s coach Tayfur Havutçu, who was dealing with criminal charges related to match-fixing. Carvalhal was paid half a million euros.

Mendes had negotiated good salaries for his players. Sidnei was paid €1.1 million for a year’s work, and Bebe, €700,000. Fernandes signed a contract worth €6.3 million over three years. Simao earned €7.2 million for over a three-year contract, and Almeida nearly €10 million over fours years. The young Alves earned €300,000 a year.

€100,000 per minute for Alves

The most controversial of the Portuguese Wave transfers was that of Julio Alves, a 20 year-old midfielder from the city of Póvoa de Varzim. The Alves deal took place on the last day of the summer transfer window and both Mendes and Bulut outdid themselves, convincing an enamoured Beşiktaş to fork out over €6.2 million for a what was essentially a worthless player.

Mendes’s relationship to Alves began in January 2010, when the midfielder was 19 years old. Although he hailed from a famous football family – he is the younger brother of Portugal international Bruno Alves, and former Benfica defender, Geraldo – he was by no means a wunderkind.

In fact, leaked documents show his salary at Rio Ave was a mere €13,800 a year. Transfermarkt listed his value at the time at a generous €700,000. None of this phased Mendes. In July 2011, the superagent arranged for Alves – who had at the time played nine games in Rio Ave’s first team, only three of them as a starting player – to move to Atletico Madrid, who paid an inexplicable fee of €2.6 million.

Alves never set foot in Madrid, however. Within a month, Mendes had convinced Beşiktaş and Demirören to agree to pay a €3.1 million transfer fee, 55 percent of the economic rights, for a player who had suddenly upped his value again to €6.2 million. The fee represented a total increase in value of 758 percent in only a few months.

Internal documents contained in the Football Leaks collection reveal that the remaining 45 percent of the player was owned by Mendes-connected, Quality Football III Ireland Limited, the same fund that organised the Almeida transfer six months earlier.

Alves would play a total of only 14 minutes for Beşiktaş. A year later he was loaned to Clube de Portugal before being formally released on a free transfer, in March 2013. When Demirören left Beşiktaş in January 2012, Alves’s transfer fee remained unpaid. Eventually the club settled the bill for €1.4 million, plus Alves’s outstanding salary: With only 14 minutes pitch time under his belt, Alves had cost Beşiktaş €100,000 per minute of football.

There are no details of commission payments to Mendes and Bulut for the Alves deal found in the Football Leaks data.

By the time Demirören and Mendes had concluded their business, the president had committed a financially struggling Beşiktaş to around €63 million in transfer and loan costs, salaries, and income taxes: 10 percent of which went to Mendes – mostly though an offshore company.

The cash earned by Mendes and Bulut from deals with Beşiktaş (Credit: The Black Sea/ Nisha Vasudevan)

Legalities Ignored

Although Mendes had processed the €2 million fee for the Quaresma deal through his Portuguese company, by January 2011 he had switched jurisdictions and begun to funnel the multi-million euro payments from Beşiktaş to his Irish company, Gestifute International.

Gestitute and Mendes’s other Irish company, Polaris Sports, as well as Multisports & Image Management, owned by his tax accountant Andy Quinn - are now being audited by Irish tax inspectors as part of a global tax investigation into Mendes’s business practices. The EIC network and its partners revealed today that, between 2008 and 2016, Mendes and his wife received around €100 million from Gestifute without declaring it as dividends.

All of the Gestifute contracts with Beşiktaş from 2011 are illegitimate and against rules that govern football agents, say three separate lawyers and a financial expert in sports money laundering, who analysed the language of the documents in question.

The problem? Each of contracts were signed on behalf of Gestifute by Mendes’s tax accountant, Andy Quinn, who is not registered anywhere with FIFA to conduct player agent services.

The presence of Quinn’s signature “is against all the rules and regulations of the time,” said Serhat Yilmaz. “The rules were very clear cut. [Andy Quinn] does not have a license to be an agent, and does not have any power to sign such contracts. He cannot be included in any part of the transfer process.”

The expert adds that Beşiktaş “has the responsibility to make sure that the agent himself is involved and he has a license,” to the same extent as Mendes. “I am not entirely sure why Mendes doesn’t put his name [on the contracts].”

“It is possible that the [Mendes] gave power of attorney to [Quinn] to sign these contracts.” said lawyer Mert Yasar. “But then the agent’s name has to be on the signature part and the accountant signs on behalf of him.” It was not.

“It seems everybody ignored this,” he added. “If there is a problem in the contracts, then the TFF says that [the contracts] have to be nullified, and fine the club fined.”

Yilmaz also expressed concern that the Turkish Football Federation, now headed by Demirören, which is supposed to receive copies of all intermediary contracts, should have told Beşiktaş to draft them properly. "TFF should have stated that the contracts are not executed properly and should have told the club to change them,” he said. “The TFF doesn’t seem to have done that. Obviously there are some political issues.”

Neither the Turkish Football Federation nor Beşiktaş responded to questions on this issue. For the majority of the €6 million payments to Mednes, the procedure worked without any fuss. But their legitimacy would eventually become a problem for Mendes and Gestifute.

Mendes fights for his money

Six months after Demirören’s exit, Beşiktaş still owed Mendes €1.75 million in fees and Mendes began threatening legal action. The outstanding debt was from the two commission agreements Demirören signed during the 2011 summer transfer window for the transfers of Bebe, Sidnei and Fernandes.

An unpaid invoice of €1.75 million is too large to ignore. Initially Gestifute suggested to Beşiktaş in April 2012 that it might settle the bill with a €1.5 million over 10 months. But by October, nothing had happened, and so Mendes turned to his Turkish partner, Ahmet Bulut.

Bulut brought in his right-hand man, Sami Dinç, a sports law attorney who was previously hired by the TFF and another Turkish club, Fenerbahce. Dinç was not long out of jail, where he spent more than a year facing charges of match-fixing over his conduct while at Fenerbache (The charges appear to have been dropped).

In emails to Mendes, seen by The Black Sea, Dinç recommended trying to solve the Beşiktaş issue in the Turkish courts with a demand for payment order. “Upon a possible objection by Beşiktaş,” Dinç told Mendes in October, “then we have to apply to the local courts to annul this objection based on the club's own records. This looks the easiest and less arguable way.”

As predicted, Beşiktaş rejected Gestifute’s application by Dinç, declaring in an letter in December 2012 that the club was “not in debt to Gestifute International Limited as it is claimed. Thus we object the claimed amount.”

Dinç then informed Mendes that, “As I told you in the beginning, a local court in Turkey would easily make a decision that an arbitration procedure was determined in the contracts according to the special jurisdiction clause and reject our claims based on lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.”

Licensed FIFA agents would usually have contract disputes of this sort resolved by FIFA’s arbitration system, but this presented a problem for Mendes and Gestifute. “As you may well be aware,” Dinç writes,”the contracts made between Gestifute International Limited, which was based on the cases, were a bit confusing and taking the dispute to FIFA was very risky at the beginning [...] because Gestifute International Limited is not a member of football family.”

FIFA and TFF rules are clear: Transfers must be conducted with a licensed FIFA agent and details on agents, contracts, and payments, entered into the FIFA Transfer Matching System system, known as TMS, in order to promote transparency and fight unlicensed activities.

Dinç concludes that they may win the dispute in the Turkish courts, but this would take a great deal of time, so the case was “a bit problematic.”

Beşiktaş could have stalled the whole process and avoided ever paying the fees. But instead the club opted to enter into informal negotiations with Dinç and Bulut, who managed to obtain promissory notes whereby the club agreed pay a reduced figure of €1.5 million, in 12 instalments.

In 16 April 2013, Dinç informed Mendes’s lawyer. Osorio that, “In accordance with the agreement made between Mr. Jorge Mendes and Beşiktaş, 1.500.000,00-Euro was wired to my account today.”

Gestifute’s bank records show that Dinç transferred the money to the company account the next day. Ahmet Bulut is not forgotten. Bulut and Mendes signed a contract for the Turkish agent to receive €845,000, which he did, albeit unofficially.

New president, old tricks

When Beşiktaş appointed its new president Fikret Orman in 2012, expectations were high. Orman declared that his “management style is the opposite of Demirören’s”, and many believed him a reformer, determined to keep a healthy distance between Beşiktaş, Mendes and Bulut, and the troubled days of Demirören, which had resulted in a fiscal carnage, hundreds of millions in debt to shareholders, clubs, players, and even Gestifute.

Well-placed senior sources inside Beşiktaş tell The Black Sea that Orman’s resistance was fleeting. Eventually, he allowed Bulut and Mendes to regain considerable influence in the club and push out those who objected. In 2016, Mendes and Bulut cut another deal with Beşiktaş, this time a two-year loan agreement for Brazilian attacker Talisca. The agents and the owners even sat together during negotiations. Beşiktaş, it seems cannot shake off its addiction to the Mendes methods.