On November 19, 2023, a patrol boat of the Guardia di Finanza intercepted a small tanker just over ten miles from the southern coast of Sicily. The authorities wanted to check if the vessel met the requirements for sailing the Mediterranean. It appeared to lack the “double hull,” a mandatory safety feature designed to prevent its poisonous cargo from spilling into the sea in the event of a collision.

Today, the ship remains under seizure, not for environmental or safety reasons but over suspicions that it illegally smuggled diesel into Italy. The ship's route strongly suggests that its liquid cargo was at least partly of Russian origin.

When the authorities arrested the nearly 60-year-old ship, known as the Aristo, it was in the process of transferring hundreds of thousands of litres of diesel— almost 670,000, two-thirds of the total — to another vessel.

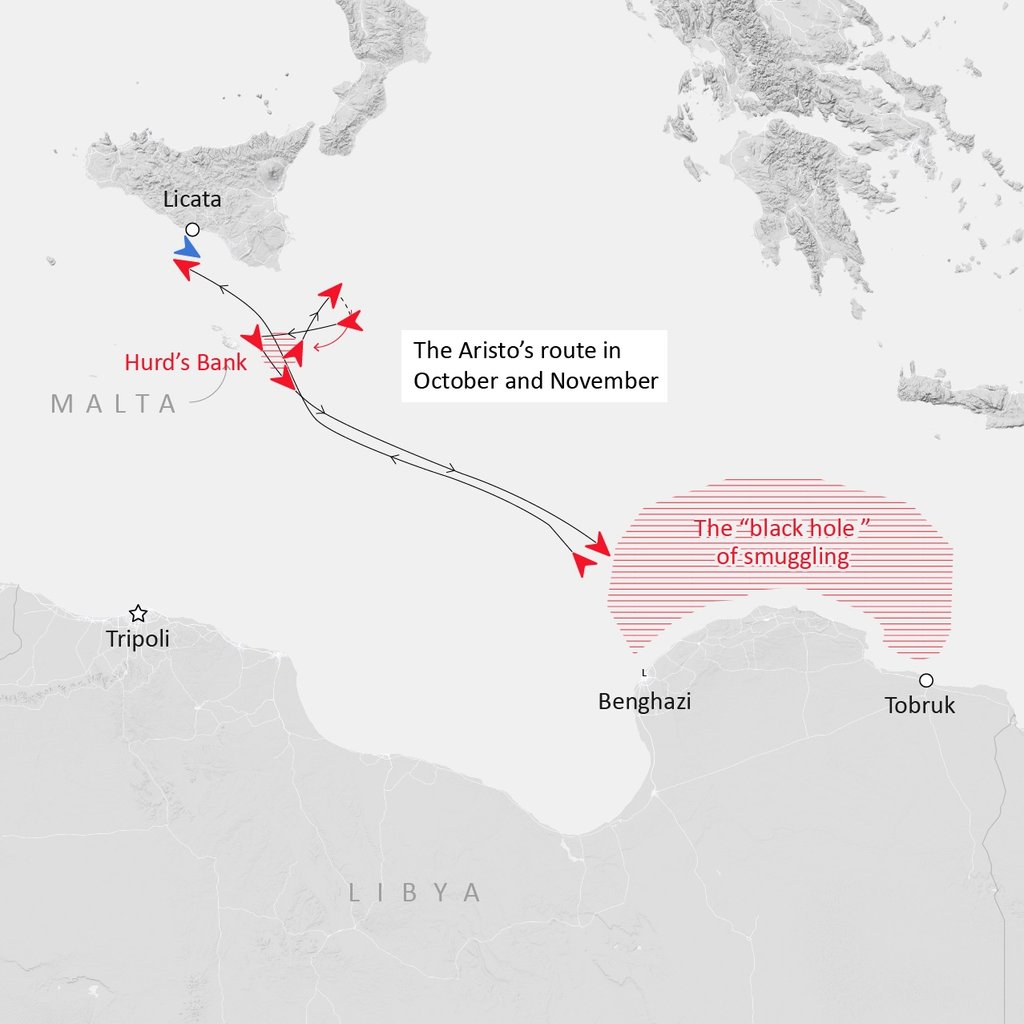

The Aristo – 60 meters long, built in 1964 and flying the Cameroonian flag - had exhibited a series of strange manoeuvres before its arrest, which had no apparent commercial explanation. Traceable through ship-tracking websites, it showed it spent months floating near Hurd’s Bank, a shoal where it’s easy to anchor, 16 miles from Malta and beyond the 12-mile boundary that marks the edge of the country’s territorial waters. The area is a known “hot spot” along Mediterranean smuggling routes. But the Aristo didn’t stay anchored there for long – soon, it headed for Libyan waters.

Since the beginning of the summer, it made four long trips to eastern Libya, through a stretch of sea between Benghazi and Tobruk, where it turned off its Automatic Identification System, known as AIS, for several weeks before reactivating it and heading back to Malta.

From the available data, it is impossible to know for sure what Aristo was doing in this period. But Libya is, like Hurd’s Bank, another hub for smuggling in the Mediterranean.

The route of the Aristo

On 2 October 2, 2023, the Aristo was anchored in Hurd’s Bank, a few miles east of Malta. Between 2nd and 3rd, it travelled a few miles, almost in circles, turning off the AIS for short periods before returning to the same position.

Then, on 10 October, the Aristo headed for Benghazi. It turned off its AIS again. For over a month, the location of the Aristo was unknown. When the crew finally reactivated the AIS on 14 November, they’d set a course northwards to Europe. Five days later, the Aristo docked alongside the Normand Maximus off the coast of Licata, Sicily. The operation was brief. The respective AIS systems recorded the interaction clearly.

It was the Aristo’s fourth journey that year, having travelled the same route in late June, early August, and early September. In all cases, the ship arrived in an area between Benghazi and Tobruk in northern Libya, turned off its identification systems, and reappeared on its way to Malta.

The route of the Aristo from early October to mid-November (Lorenzo Bodrero/IRPI)

The most recent report from the Libyan Court of Auditors, dated 2022, states that 40% of the country's fuel imports are re-exported illegally by land and sea. Over 40 tankers followed the Aristo's route and “disappeared” in the same areas during the first six months of 2024. These were all small to medium-sized tankers, more than 15 years old, recently sold to owners hidden behind shell companies registered in tax havens and flying the flags of countries that exercise minimal oversight of vessels.

Ships with these characteristics are defined by analysts at Lloyd’s List Intelligence, one of the leading information and analysis sites for the global maritime industry, as part of the “dark fleet,” a shadowy fleet of often older ships that transport petroleum products from countries under EU sanctions.

If Italian authorities confirm that the Aristo’s fuel originated from a sanctioned country, it would add the 60-year-old oil tanker to the growing list of dark fleet vessels shifting sanctioned diesel into Europe.

When the Guardia di Finanza intercepted the Aristo, its crew were in the middle of a ship-to-ship transfer of diesel to a vessel specialising in maritime construction called Normand Maximus, owned by the Norwegian group Solstad, a major shipping company.

At that time, the Normand Maximus was under contract with Saipem, the Italian engineering giant in the energy industry, controlled by the state through shares held by Eni and CDP Equity.

Hurd’s Bank and the “black hole” of smuggling

Hurd's Bank near Malta, and the "black hole" of smuggling along the Libyan coastline (Lorenzo Bodrero/IRPI)

Hurd’s Bank is a shoal just outside the boundary of Malta’s territorial waters. It is an easy place to anchor, and many ships stop here while awaiting orders. Several investigations reveal it as a favoured location for ship-to-ship transfers of contraband, including people, drugs, and oil.

The area north of Libya where the identified ships turned off their tracking systems is bordered by Benghazi and Tobruk and stretches about 50 miles off the Libyan coast. Ships from both the east and west disappear into this “black hole” only to reappear while already on their return journey.

The Normand Maximus was working for Saipem on gas extraction facilities from the Argo Cassiopea fields, managed by a joint venture between Eni and Energean, a Greek-owned oil and gas company. The fuel taken from the Aristo was presumably intended for one of the platforms of the four underwater wells. The court ordered the internal tanks to be sealed, preventing Normand Maximus from removing the fuel while authorities determine its origin.

According to investigators, when asked to produce documents proving the lawful purchase of the diesel fuel and its origin, neither Ibrahim Aly Abbas Barakat, the Egyptian captain of the Aristo, nor Erling Sandviknes, the Norwegian captain of the Normand Maximus – both highly experienced sailors – could provide any.

When validating the seizure, Micaela Raimondo, the preliminary investigations judge of the Agrigento court, said that this appeared to be "a 'black' transfer operation intended for illicit purposes" and based on " emails of little commercial clarity." Seals had been placed on both Aristo and Normand Maximus.

But at the beginning of 2024, Raimondo released the Norwegian vessel.

"The investigations are ongoing, and there has been no indictment," said Gianluca Gullotta, the lawyer defending Abbas Barakat, the Aristo captain. The lawyer did not provide any further clarifications on the case.

According to sources close to the investigation, Saipem claims to be extraneous to the affair: the Normand Maximus cannot be directly traced back to Saipem because it is owned not by them but by a Norwegian company.

As is often the case, the diesel was purchased through a broker responsible for sourcing the supplier. And Saipem is claiming they had little influence on this process. Neither the Italian company nor the lawyer defending the commander of the Normand Maximus responded to requests for comment.

A satellite snapshot of the port of Benghazi, Libya, taken in March 2024 (PlaceMarks)

satellite image of the port of Tobruk, Libya, taken in June 2024 (PlaceMarks)

Doubts about the Aristo

The figures behind the Normand Maximus – the shipowner and the charterer – are prominent names of large international companies. The same cannot be said for the Aristo.

It is not obvious who is behind the shipowner company, Medgreen Shipping and Trading S.A., the name that appears on the Aristo’s insurance policy.

The address on the insurance documents is in the Marshall Islands. Stavros Halikias, the Greek lawyer on the legal team representing Abbas Barakat and the shipowner, claims that the company is Egyptian.

“Medgreen Shipping and Trading rented the vessel to another company, which was responsible for the contract with Saipem and the crew on the ship. This is also the company I represent. The name? At the moment, I can’t reveal it; there’s an ongoing investigation,” Halikias said.

Halikias added that the ship was stopped over tax-related issues, not evidence of illicit cargo. “Aristo wasn’t detained because of the fuel’s origin but because it supplied fuel to a vessel operating within Italian territorial waters,” he said.

The lawyer claimed that he had provided the Italian authorities with evidence of the frequent communications between the Aristo and the Normand Maximus. “We only supplied Normand Maximus with one delivery. There’s written communication showing that the decision to conduct the exchange in Italian territorial waters wasn’t made by the Aristo’s captain.”

Since 22 January this year, the crew of the Aristo has officially been in a state of abandonment, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the UN agency responsible for labour issues.

In contractual terms, this means that from that moment, Commander Abbas Barakat and the First Officer were no longer in contact with the shipowner. The other crew members —five Indonesians and one Egyptian—remained on board for several months before finally being permitted to return home, largely thanks to the efforts of the Welfare Committee and the International Transport Federation (ITF), the international transport workers’ union. This version is disputed by Halikias.

“We didn’t abandon the crew; we paid their salaries and sent provisions on board. Unfortunately, for a long period, we received little cooperation from some maritime agencies in Augusta, and the problems that occurred weren’t our fault,” the lawyer said.

Rosario Litrico, president of the Welfare Committee for Seafarers in Augusta, Sicily, where the ship was docked, had initially provided basic assistance to the seafarers still on board. Litrico took a different view, telling the Greek lawyer by email: “The shipowner only took care of the provisions in the last month. Everything that was done earlier was possible thanks to our resources. There are invoices to prove it.”

Journalists at IrpiMedia tried to contact one of the repatriated seafarers but received no response. They did not want to speak to the investigators either.

The diesel on board the Aristo may soon be transferred to a fuel depot. The Agrigento prosecutor’s office is assessing the possibility that the insurance policy is fake: the company that underwrote Aristo’s policy is based in Florida, and the certificate of insurance was issued by the port authorities of the Kingdom of Tonga.

“In cases like these,” explained Mariano Cannioto of the ITF, “the main issues we encounter stem from the fact that the ships have flags of convenience granted by countries, like Cameroon, that have not ratified the 2006 Maritime Labour Convention, which sets specific obligations for states when a ship is abandoned.”

Using the model of Lloyd’s Intelligence, the characteristics that define the dark fleet identified are the suspicion of fake insurance (in the Aristo case); the violation of the Paris Memorandum of Understanding (which applies to 27 countries across Europe and the North Atlantic and sets safety and inspection requirements for ships); the routes taken in the “smuggling triangle,” with long periods where the AIS is turned off; the lack of any port entries; and excessive ship-to-ship transfers of products (mainly conducted in high-risk zones).

The dark fleet system

The Aristo

The online shipping database Equasis shows that until January 2023, the owner of the Aristo was the Greek company Leventakis Shipping Co. And it is not the only vessel among the more than 40 we identified as suspicious that was formerly owned by this company. It also owned the Chios until September 2023, when it was transferred to a Lebanese company and now flies the Comoros flag.

The timing of the sale, the opacity of the buyer, and the age of the vessel are among the criteria analysts at Lloyd’s Intelligence use to determine whether a ship belongs to the dark fleet, the ever-expanding group of companies that transport petroleum products under sanctions, originating, for example, from Russia, Iran, and Venezuela.

In 2023, the analysts added various shades of risk to the dark fleet, from light grey to black, depending on the number of suspicious characteristics and the operations in which a ship was involved.

The Aristo, and potentially the Chios, fall into the highest risk category: black. Other identified ships have similar characteristics, though it is not possible to define a subcategory for all of them.

To identify the ships of our Mediterranean dark fleet, we filtered all non-crude oil tankers: They must be over 20 years old, under a maximum size (much larger ships are rarely used for these kinds of smuggling operations because they attract more attention), and must have turned off their AIS systems within an area we defined as the “black hole of smuggling” between the Libyan ports of Benghazi and Tobruk.

The Mediterranean dark fleet itself is divided into two groups, depending on the area in which they operate. One group sails east and north: many frequently dock in the Black Sea at the port of Novorossiysk, one of the main exit points for Russian petroleum products. Another group seems to depart from ports in Syria, Turkey, and Northern Cyprus, which all then head into Libyan waters to turn off their tracking systems.

Found in this category is the Nobel, an old tanker built in 1997 and owned by Russian Rusprimeexport LLC until 2022, the year of the sanctions, when suddenly its owners became “unknown.”

The Angelo 2 was until 2022 owned by Uvas-Trans LLC from Kerch, in Crimea, occupied by Russia since 2014. It was flagged in 2018 by the UN Panel of Experts on Libya for involvement in a suspected case of smuggling from eastern Libya. The Grace Felix made several trips of this type we describe before being stopped in Albania for smuggling Russian diesel in January 2024.

The other tankers in the dark fleet apparently handle the second part of the relay. These are ships like the Aristo, which sail westward (mainly from Malta) toward Libya, turn off their AIS, and reactivate it on the way back.

This second leg of the journey, when it ends in Malta, is likely followed by a third, as these ships rarely dock, remaining mostly in open waters at Hurd’s Bank, a notorious smuggling hotspot, where they wait to transfer the product to a third ship that then completes the journey.

The Aristo seizure occurred because the actions were carried out within the 12-nautical-mile limit of Italy's national territory. When suspicious transfers take place in international waters, however, authorities often face two insurmountable problems: First, law enforcement does not have jurisdiction to act and often cannot even monitor what is happening so far from the coast.

Then, even if they spot suspicious behaviour, one of the two ships must fly the same country’s flag as the law enforcement vessel, or they cannot intervene. Most suspicious operations happen in international waters and when all tracking systems on the ships in question are turned off.

We have never been able, for instance, to observe the moment when ships doing the relay from the east (Russia-Turkey-Syria) meet those coming from the west in the seas north of Benghazi.

The explosion of the “black market” for fuel in eastern Libya

According to international observers, diesel smuggling in Libya is growing exponentially every year, a trend also confirmed by the Libyan Court of Auditors. The country has very limited refining capacity for its own crude oil and maintains a massive subsidy program to import large quantities. The main supplier is Russia, which sends more than a third of all the fuel that Libya receives.

Smugglers are known to prefer to work with imported products, which they consider a higher quality. Regardless of whether the origin of each smuggled shipment can be confirmed, it can be safely estimated that at least one in three litres of all smuggled diesel is Russian.

It is a business that is now valued at over $10 billion a year.

This illicit trade is often managed economically through an exchange: Libya “pays” for the fuel it imports with crude oil, further undermining the possibility of “tracing the money” and making the process even more opaque.

Importing Russian oil is not illegal in Libya. But the smuggling system, which grew precisely from the application of sanctions after the large-scale invasion of Ukraine, allows Russia to evade Western sanctions. For European companies that purchase the sanctioned fuel, there is a huge economic advantage: the price is lower.

All of this helps to strengthen the increasing criminal control that the powerful Haftar family is exerting over eastern Libya, led by ’strongman’ Khalifa Haftar, commander of the Libyan National Army. While a few years ago, smuggling was the prerogative of competing militias in the west of the country, it has now drifted firmly eastward under the Haftar’s protection. Massive profits are up for grabs, and the result has been a boom in corruption and violence, with smuggling reaching a scale not seen before.

Opening credit: Hurd's Bank, an anchorage point for oil tankers off the coast of Malta (William Attard McCarthy/Alamy)

Story by IRPIMedia

Edited by Lorenzo Bagnoli & Craig Shaw

Visuals: Lorenzo Bodrero

With the support of IJ4EU