In south-central Bucharest, 43 year-old Ciobi is standing by the water cooler upstairs in a ramshackle villa housing Italian charity Parada, which helps train the capital’s homeless as circus performers.

His face is sweaty. The heat is rising to 30 degrees outside. He asks if I want some water. I say yes.

“What was your name again?” he says.

“Michael,” I say.

“As in Michael Jackson?”

“Yes,” I say. “But I’m not black.”

“By the time he was dead,” says Ciobi. “Michael Jackson was not black.”

He laughs, leans back, opens his arms and starts to sing.

“I’m White! I’m White! You know it!”

I realize he is singing the melody to the chorus of ‘Bad’ by Michael Jackson – ‘You know I’m bad. I’m bad. You know it.’

I think he is confused. He believes the lyrics are not ‘I’m Bad’ but ‘You know I’m Black. I’m Black. You know it.’

He is attempting to make a play-on-words with the song.

It is clear that he is at ease with singing. He understands the key, the intonation and has the confidence to perform spontaneously.

But he stops, as though someone has asked him to shut up, bows his head and pours me a cup of water in silence.

Ciobi is a former wedding singer who spent a decade smoking heroin. In 2010, he switched to injecting legal highs bought over the counter in head-shops, which he shot into his veins three times a day.

This addiction ended in a stroke that killed his career as a troubadour and left him paralyzed, without money or a home.

Smack diva

Trained as a carpenter, Ciobi was working on a building site in the late 1990s when he gave up his job to pursue a career in music. Hooking up with a band, he compered weddings, baptisms and receptions, gaining up to several hundred Euro for a night’s work.

“Usually at Romanian parties there is a singer who performs folk music, a gypsy who sings [Balkan folk-pop fusion] Manele and a guy on guitar or keyboard who plays popular songs,” he says. “I used to do all these things. I, alone, carried the wedding.”

Ciobi talks up a repertoire that stretches across four languages – classic Romanian chanson by Nelu Ploiesteanu, The Godfather theme sanitized into the love song ‘Parla piu piano’, ‘La Vie en Rose’ and Lionel Ritchie.

“Hello,” he sings to me in English, moving his head back, trying to hit the high notes. “Is it me you’re looking for?”

To ease him through the nights as a human jukebox, Ciobi smoked smack.

“Heroin was the gas for my car,” he says. “When I was low, the little light that signaled that I needed to refuel would start blinking. If the car didn’t get a full tank, it wouldn’t start. And then I refueled and the car started running again.”

This was not a secret.

“Everybody in the club knew, from the doorman to the cleaning lady, that from nine to ten at night, I went to the toilet to roll up a heroin cigarette and stayed outside to smoke it,” he says.

“Till morning, everybody was dancing on the tables. I didn’t have a problem doing my job. I didn’t need to steal in order to buy drugs because I had a more than decent wage.”

New sensation

In 2010 Ciobi’s friends encouraged him to mix the heroin with a type of high available from recently-opened head-shops. Known as ‘Legale’ in Romanian (‘Legal Highs’), the white powder was a stimulant, which, mixed with the depressant of heroin, gave a ‘speedball’ effect, where the user oscillates between relaxation and invigoration.

“My poor adrenalin didn’t know which way to go,” he says. “In Bucharest, it was a new sensation. Every normal guy became someone else. If you could jump one meter, with Legals you could jump two meters. It was an explosion of energy. And when you had sex with a woman, that would take ages.”It was two years into the financial crisis gripping Europe. Drug addicts were hit by the downturn and were looking for cheaper alternatives to heroin, which, on the Romanian market, was low in purity.

Legal highs were cheaper than smack and users did not suffer a possession charge if they were arrested by the police.

“Back then I didn't know that heroin is like milk compared to legal highs,” says Ciobi. “Heroin is a thing you can get rid off, with certain withdrawal symptoms, after four or five days. But legals mess you up.”

Ciobi injected brands such as Pure, Magic and Gold Space, all synthetic stimulants usually snorted as a cheap alternative to speed. Head-shops sold them as ‘bath salts’ or ‘cleaning powder’. On the wrapping it was written that they were ‘not for human consumption’, which protected merchants from the accusation they were profiting from dangerous drugs.

“With Gold Space, the first dose would give me some energy,” he says. “The second would entice me to drink, talk or have sex and the third would bring paranoia. But I could never have enough. I could take three doses in two hours. The more I shot, the worse I felt.”

Ciobi was using the drug daily and often with friends. However they all began to experience symptoms of schizophrenia.

“Everyone has his own fear,” he says. “For example, it’s five of us in the room and one of us is scared of dogs; then he imagines dogs coming to get him, trying to bite him and, if he sees a dog in the street, then he will climb a tree and stay there for the whole night.”

Ciobi believed people on public transport were a threat.

“I looked at a person in a tram,” he says. “They were far from me, but I stared at them. Any gesture they made, I took it personally. If they dropped their keys, in my mind they did it on purpose, to scare me.”

This state of mind stopped him from working.

“I would be at a wedding with 200 people. The second I took the microphone in my hand, I had the feeling everybody was giving me funny looks and that I was not doing the right thing,” he says.

One time, in front of a table, where a customer was paying for a private song, he seized up, the words and music mute.

The man in charge of the club came over and said: ‘I don't like it, get somebody else to sing.’

But he continued to inject. Whenever he had money in his pocket, he would not buy food, but Legals.

“The second I would inject my first dose, my well-being would disappear,” he says. “I would hurt myself. Many times I went to the shops crying. I was crying because I knew what was about to happen to me. This remains an enigma. It was like - how could I walk down the street, fall down a sewer-hole, crack my skull, and the next day, go back to the same part of the street, and fall down the same hole?”

Between 2010 and 2012, under new powers to curb the trend in legal high use, Romania’s police raided the head-shops, gaining the right to shut them down.

However some store-owners took their stash and sold drugs out of their car, around the corner from where the shops used to be. “The business turned from retail into wholesale,” says Ciobi.

The dealers began to mix the Legals with other chemicals, such as chlorine, Ciobi argues.

“My vein were shriveled, like a pair of trousers that fits at first, but shrinks after washing,” he says. “Meanwhile I would sweat with the smell of chlorine.”

Knocked out loaded

In the beginning of 2012, Ciobi was on the street, injecting a strong packet of powder of the now illegal stimulant. The moment after the needle left the vein, he fell on the street on his left side and could not move.

Although in pain, he woke up and made his way home, but fell down again in on the pavement.

He says a Spanish guy walking past helped him get to the Accident and Emergency of a hospital in north Bucharest.

I try to push him on who this was and how he knew he was Spanish, but Ciobi will not give further details.

He seems to think it is natural for the Spanish to be wandering through Bucharest, prepared to take pity on overdosing addicts in the middle of the street.

In the hospital, Ciobi could not swallow. His muscles and larynx were paralyzed. A CT scan showed that he had experienced a minor stroke.

He points to the left side of his face.

“When I put the razor to my face to shave myself, I do not feel anything,” he says. “I can hear, but can’t feel my face. If I slap myself on the right side, it hurts, but here, on the left, I can hit myself with a hammer. I don’t feel a thing.”

For months a bizarre mental state seemed to force him to charge into passers-by.

“I had the tendency to fall over couples,” he says, “for example if you were to walk by with your girlfriend, I would fall over her. You would say: ‘What are you doing? Are you touching my girl’s breasts?’ By the time you realized that I was sick, you would have punched me.”

Moving on up

His body near-arthritic, his speech stuttering, his gait confused and his weight dropping to only 53 kilogrammes, Ciobi arrived at the Parada foundation, which has a small gymnasium with mats and exercise equipment.

Every day, he started to do gymnastics, pantomime and break-dance, working with performers, disadvantaged children and street kids. Here Ciobi had access to meals, a daily bath and clothes. Soon he gained 17 kg in weight.

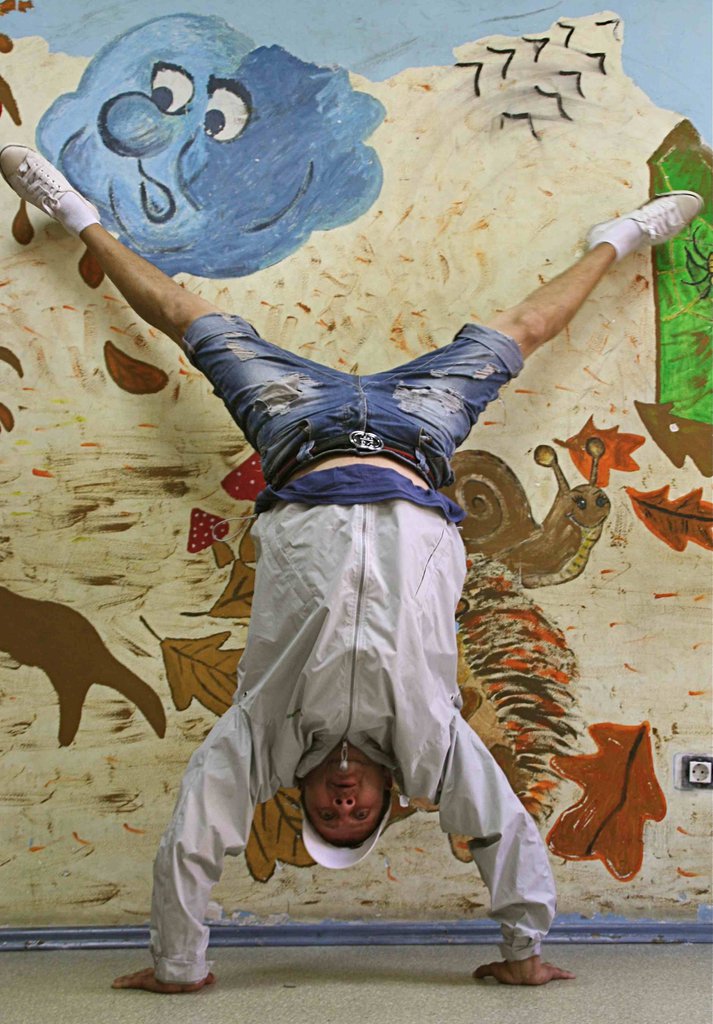

Ciobi shows me the gym. A carpeted room with plastic equipment, lockers and naive murals on the walls of rain-clouds, apple trees and hedgehogs. Children run through the space, throwing juggling balls at one another.

Standing up straight in the centre of the room, Ciobi moves his hands and his head in a rigid imitation of a robot, performing a medley of pop, lock and wave moves popular among 1980s dancers.

He lies face-down, close to the carpet, held up by his bent arms. Turning to the left, he makes the first two or three moves of a breakdancing spin. Getting up, against a mural of a countryside scene, he stands on his head, his face red and strained, but after a few seconds, he eases himself down. Standing up again, he throws three skittles into the air, which propel for a few turns, before falling to the ground.

Sweat runs down his forehead. He needs to sit down.

“Slowly I recovered my physical health,” he says.

However Ciobi cannot sing anymore.

“I try,” he says. “Some people forget the words, but I forget the melody. When I sing it is like I am combining two songs into one.”

Street Hassle

Ciobi spends the day at the centre. At night he lives on the streets. In summer, he stays in a park in Piata Minis in east Bucharest, where he is comfortable sleeping rough.

“There are people who live there who know me and know I used to be a normal person,” he says. “Any bench I sleep on, no one says anything, because I am a clean person. All policemen who come and ask for my ID, they know me.”

When it rains outside, he cannot sleep in the open air. “Then I go to the apartment block where I used to have a flat,” he says, “and I sleep on the staircase.”

Ciobi has a teenage daughter. Her mother died at 29, when the child was eight. Now she lives with her grandmother. Ciobi also stayed in the flat with them. But when he was on Legals, he says “nothing else mattered” and he was reckless with his injecting equipment. One day his daughter found a syringe in the bathroom.

“I said to myself that instead of appearing like that in front of my kid, I’d better leave,” he says.

At this point Ciobi’s eyes moisten.

There are holes in the sides of his sneakers. He has a telephone, which he pulls out to show me. A chunky black Nokia from a decade ago, grey with bruises and scratches. It works, but needs a Simcard. He wants to call his daughter.

But he has no cash.

He complains that he needs to walk and he needs to talk. He points to his phone and to his shoes. Right now he can’t do either of these.

He moves his head about, then mumbles something I cannot understand.

I am not sure what he is asking for, but make a guess.

“Money,” I ask? “Do you want money?”

He doesn’t answer.

I take this as an affirmation.

I tell him it is not ethical for journalists to give money to people they interview.

But he has suffered decades of substance abuse, as well as a physical and mental breakdown and is now living on the streets, so what does he care about journalistic ethics?

I think about the horrible situation this puts us both in.

“I will only give you money if you put it to good use,” I say, but I sound sanctimonious. “You must buy a simcard for your phone and some shoes.”

Yes, I am aware this is a pathetic liberal compromise.

I give him 100 RON, about 25 Euro.

There is a caveat.

I tell Ciobi he must use it to call me when he gets a new number.

What about the future, I ask. This can be a cynical question to put to someone who does not have an address, a job or his health. It can sound like I am teasing.

He says he wants to regain his fitness and work on a construction site or as a security guard.

But due to his sickness, he runs out of energy.

“People don’t understand that for me a day of work equals ten days for another person,” he argues.

But he says he has the determination to continue a clean life, to get back on track and never to go back to Legal Highs.

“I must go forward,” he says, “at least like a man.”

Ciobi has to leave.

He must rehearse for a performance with Parada at the French Ambassador’s residence.

Holding my hand tightly in farewell, he looks away and says he will call me.

Did he call me?

What do you think?

- All photos by Michael Bird

- Thanks to Valentin Simionov, Corina Mica, Aurore Iacobescu and Parada for making this article possible.