On a chilly November morning in Nyon, Switzerland, in the Ebbe Schwartz room of the House of European Football, the headquarters of UEFA, around two dozen men meet to discuss Russia’s football market.

They are senior figures from UEFA’s Club Financial Control Body (CFCB), the Russian Football Union, and arguably the biggest club in Russia, President Putin’s favourite team, FC Zenit Saint Petersburg.

The meeting is at the request of Jean-Luc Deheane, Belgium’s former prime minister and the head of the UEFA’s financial investigation team, who for the past few months has led a probe into Zenit’s finances; specifically, the nature of its lucrative sponsorship deals with its ultimate parent company, Gazprom.

Unlike almost every other club competing in European football, Zenit, one of the most successful teams in the Russian Premier League, is owned by a financial behemoth. Gazprom is Russia’s state energy company and it has annual revenues of over €100 billion. Practically, this gives it and Zenit near-limitless cash.

On this Tuesday morning of 12 November, 2013, Zenit’s general manager, executive and financial directors, and head of strategic planning are justifying why Gazprom pumped €113 million into the club’s coffers in 2012, a significant cheat of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play rules. These regulations place limits on club spending, debt levels and shareholder bailouts.

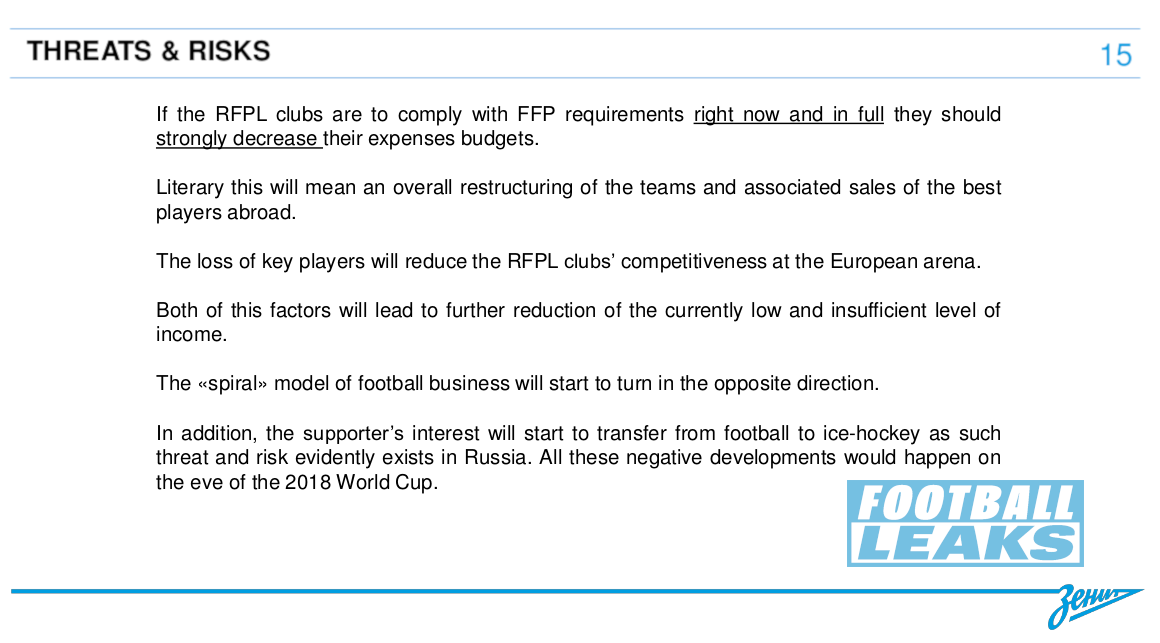

Zenit’s arguments to UEFA are uncomplicated, highlighting Russia’s poorer population and the inability of the national league to generate the revenues of their European counterparts. The technical and digital infrastructure is also weak, say club officials, and digital piracy is out of control. State subsidies are unavoidable.

“If [Russian Premier League] clubs are to comply with FFP requirements right now,” Zenit tells UEFA’s investigators, it means they will be forced to sell their best players. This will reduce “clubs’ competitiveness at the European arena,” and Russians will begin to turn away from football and towards ice hockey.

In one of the slides of its presentation titled 'Threats and Risks', Zenit delivers an ominous warning: “All these negative developments would happen on the eve of the 2018 World Cup,” in Russia.

The threat of disruption to the World Cup resonated with UEFA, it seems. Six months later, in May 2014, the investigative chamber settled the case against Zenit through a secret agreement that allowed the club to avoid exclusion from the Champions League.

The case of Zenit is not unique.

An investigation by The Black Sea and the European Investigative Collaborations network, based on new Football Leaks documents shared by German newsmagazine Der Spiegel, reveals that UEFA’s financial control body covered up similar schemes at state-owned Russian football teams, FC Lokomotiv Moscow and Rubin Kazan, and withheld information on a third case, at FC Dynamo Moscow.

The scale of the financial doping – a term used to describe the unfair advantages of having rich owners’ bankroll clubs – is not little. The documentary evidence, reviewed by The Black Sea, shows that in the past five years, since the introduction of fair play rules, the Russian state has injected over €1.65 billion into Zenit, Lokomotiv and Dynamo, through crooked sponsorship deals. And the practice continues today.

Last Friday, EIC network partners began publishing stories about how UEFA gave preferential treatment to Man City, PSG and Monaco by hiding their multi-billion financial fair play frauds. New revelations, at state-owned Russian clubs, are likely to further anger fans and owners of teams from the likes of Eastern Europe that were excluded from UEFA competitions for infractions arguably less serious.

UEFA told the EIC Network that it is “confident that any apparent inconsistencies that may seem evident to some, have been eliminated as the [Financial Fair Play] system has developed and become more familiar to all sides.”

Nevertheless, here’s how the UEFA's financial control body covered for Russia’s multi-billion bankrolling of its top flight football.

A plan to rein in excessive spending

For years, teams like Chelsea were lambasted by their rivals for buying their way to the top of football. Russian aluminium oligarch Roman Abramovich purchased struggling Chelsea in 2003 and began injecting huge amounts of his own cash to attract the best players. Within two seasons, the club was winning English Premier League titles and competing seriously in Europe.

After the oligarchs, came the petro-states: the United Arab Emirates bought Manchester City in 2008, and in 2011 the Government of Qatar purchased Paris Saint-Germain. A new class of elite teams emerged that no longer had to live on profits generated from football; winning squads could be built overnight.

The knock-on effect of Abramovich’s and state companies’ unbridled spending was that clubs were forced into offering higher salaries and transfer fees, leading to a boom in club debt levels throughout Europe, that reached €7.6 billion in 2010.

Introduced after the 2010 season, UEFA’s ‘Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play Regulations’ were designed to rein in football’s excesses and make the game more competitive. New mandatory ‘Break-even’ requirements became applicable to all clubs qualifying for UEFA’s lucrative ‘Champions’ and ‘Europa’ leagues and prohibit unpaid debts and restrict annual losses. The rules also place a caps on how much cash shareholders can inject into clubs to cover budget deficits; the limit was €15 million in the first year and then €10 million every year after.

To police the new regulations UEFA created the Club Financial Control Body and appointed former Portuguese attorney general and EU Court of Justice judge, José Narciso da Cunha Rodrigues to run it.

An investigatory chamber, led by Jean-Luc Dehaene, was empowered to uncover breaches and negotiate settlements on smaller matters. The most serious cases would be handled by the adjudicatory chamber, supervised by Rodrigues, where clubs faced larger fines and exclusion from UEFA competitions.

The financial doping at “Putin’s Club” was among the first tests for the new CFCB.

The suspicion: Gazprom's sponsorship deals

The cases of Zenit, Lokomotiv and Dynamo occurred between the summers of 2013 and 2015. Back in June 2013, Zenit, the larger and more popular team in Russia, submitted break-even documents to UEFA admitting to losses of €20 million, higher that the €5 million 'acceptable deviation' – i.e. allowable losses - set by UEFA.

Zenit was saved by a clause allowing willing owners to increase the deviation through bail-outs. Under this rule, Zenit's €20 million shortfall was tolerable. Shareholders cannot boost revenues via the back door, however, and UEFA specifically prohibits sponsorship deals with owners and 'related parties' from being above the 'market value'. So UEFA’s investigators were suspicious when they learned that Zenit’s sponsorship in 2012 amounted to an impressive €101 million, a sizeable contribution to the club’s €171 million income that year.

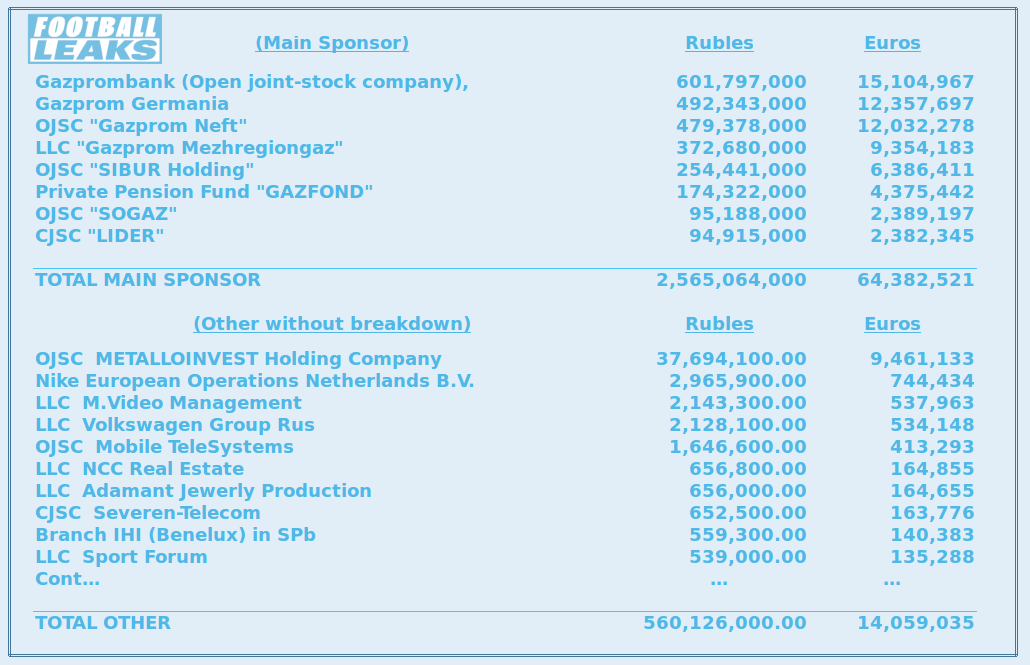

Of course, Zenit left out of its disclosures that Gazprom was behind almost all of this cash. In the accounts, the energy giant was classified as “Main Sponsor 1” and was listed with a €20.8 million payment for advertising services, in addition to a further €28 million it provided as a ‘donation’. Zenit listed the remaining €80.4 million under an equally mundane moniker: “Main Sponsor 2”.

Who was this mysterious meal ticket? UEFA wanted to know, and so on 25 September, 2013, seven weeks before the meeting at UEFA headquarters in Nyon, the chief investigator, Deheane, sent a letter to Zenit requesting copies of the €20.8 million contract with Gazprom, and a breakdown of “all other sponsorship and advertising partners” contributing to the €80.4 million.

What came back weeks later was clear evidence of financial fair play fraud. Zenit’s “Main Sponsor 2” was, in reality, a series of eight deals with Gazprom’s subsidiaries and companies close to it. Atop the pile was Gazprombank, Zenit’s main shareholder, which paid the club €15.1 million. It was followed by the Germany subsidiary, Gazprom Germania, with €12.1 million.

The list went on: Gazprom’s oil subsidiary provided around €12 million; its retail natural gas operation over €9.4 million; the private pension fund, €4.38 million. Even Gazprom's insurance firm bought €2.39 million in sponsorship from Zenit.

Included among the generous advertisers is Sibur Holding, a petrochemicals conglomerate owned by Gapzrom until 2012, after which it was sold to Russia’s richest businessman Leonid Mikhelson and its fourth richest, Gennady Timchenko. Sibur, which paid €6.4 million, is one of Russia’s largest gas processing companies and remains on good terms with Gazprom, a natural business partner. Among Sibur’s board members is Kirill Shamalov who, until this year, was Putin’s son-in-law.

This Gazprom group of eight contributed over €64.3 million to the club’s supposed ‘other’ revenue sources, leaving barely €14 million as the real sum from non-related parties. But even here, there is trickery. UEFA and Zenit appear to have overlooked the presence of Metalloinvest Holding, which with €9.5 million was by far the highest payer of 54 remaining “other” advertisers. The company’s largest shareholder, then and now, is Alisher Usmanov, who is one place behind Timchenko on Russia’s billionaire list, and a major investor in UK’s Arsenal FC. Usmanov was the long-time head of Gazprom Investholdings until he resigned in 2014.

The Gazprom veil had slipped and what remained was a series of small deals valued at barely €4.5 million; the largest of which was Nike’s €750,000. The presence of Gazprom Germania in particular is baffling: Why would a German-focused company sponsor a Russian club? Zenit did not answer. Incidentally, Gazprom Germania sponsors German club, Schalke 04, as well as UEFA.

Even discounting the involvement of supposedly unrelated companies like Metalloinvest, Zenit’s disclosure to the CFCB laid bare the extent of Gazprom’s financial doping. Calculations by The Black Sea and EIC show that the energy giant provided almost all of Zenit’s revenues for 2012, and without its generosity, Zenit’s €171 million revenues drop by 66 percent to barely €57 million.

All of this should have spelled trouble for the club.

A fake investigation

The evidence that Zenit’s finances were a con was clear as far back as October 2013, but it took the investigative chamber another four months to open a formal investigation. By the time it did, on 25 February 2014, Zenit had attempted a number of other tricks to obscure its doping funds to UEFA.

It had begun even months earlier when the club preemptively hired Australian sports evaluation and intelligence company, Repucom, to perform a ‘fair value assessment’ on its deals with Gazprom. UEFA often instructs independent audit firms to evaluate suspect sponsorship deals – and had done so with Man City and PSG - but unusually in this case it was Zenit that initiated the probe. When Repucom’s report was eventually completed, in March 2014, it was not hard to understand why Zenit’s general manager, Maxim Mitrofanov, had so confidently declared in a letter to UEFA six months earlier that Gazprom was, in fact, underpaying.

On 9 October 2013, Mitrofanov argued that the gas giant “had regularly requested and consumed services not fixed or documented by extra agreements to the contract.” In short, it was ripping off the club.

These off-contract services listed in the letter also reveal the alarming extent to which Zenit and its players are beholden to its owners. The club permitted Gazprom a “number of exclusive hospitality services inaccessible to other partners”, such as visits to the dressing room, VIP tickets, and seats at official dinners and events. Zenit’s top players were even required to give birthday greetings to Gazprom staff, its partners and government officials, as well as watch live games with them, participate in photo sessions, and social programmes. They should even visit business offices to sign autographs.

In addition, Mitrofanov tells UEFA’s control body that Zenit is participating in “a complete re-launch of [the Russian Premier League] aiming at sufficient growth of revenues generated by the league,” a project undertaken in “in cooperation with Deloitte and Repucom.”

The Black Sea contacted Repucom, since bought by U.S. brand management firm, Nielsen, to ask whether there was any conflict of interest. The firm refused to answer questions directly, citing confidentiality.

They also declined to explain how the figures from its independent fair value assessment of Gazprom’s deals appeared verbatim in Zenit’s next financial disclosures, months before the report was actually completed.

When Zenit supplied UEFA with updated accounts, in early 2014, it had performed a number of telling alterations, including rewriting its 2012 statements to match what Repucom would publish in a few weeks’ time. The club also miraculously shifted sums from Gazprom subsidiaries, including the one in Germany, to its main Russian company. Zenit also left out the €6.4 million from Leonid Mikhelson’s Sibur Limited. (Sibur did not answer our request for comment.)

At the beginning of March 2014, Repucom finalised its report, and Zenit sent it to UEFA. It upped Gazprom’s annual contribution to €75 million, a massive sum, but in spite of this generosity Zenit remained heavily in the red. Its new, two-year break-even deficit was now €92 million. And so UEFA declared the club in breach of its fair play rules.

Settlement: No risk of Champions League exclusion

With its financial problems now known to UEFA, Zenit attempted to convince the investigatory chamber’s acting chief, Brian Quinn (who had replaced a terminally ill Deheane), that it could stay afloat and supplied a business plan.

The plan it submitted was brazen. It kept Repucom’s advice and capped Gazprom’s 2012 and 2013 contributions at €74 million, but then increased these contributions to €90 million each year over the next four years. Only then, said the club, could it comply with financial fair play rules - by 2017.

The document makes clear Gazprom’s intention to continue to bankroll the club. Over the six-year period, its contributions would reach €605 million - a clear and massive breach of UEFA’s rules. But there was to be no showdown in the adjudicatory chamber. And no exclusion from the Champions League. Instead, the investigatory chamber, whose final report acknowledges these facts, offers the club a private settlement: pay a €6 million fine, apply some spending restrictions, and submit to increased monitoring for three years, and the matter can be closed.

Zenit, unsurprisingly, accepts the terms. On 8 May 2014, the club and the investigative chamber sign the settlement. Nowhere on UEFA’s website or in the agreement does it state that Zenit will be cheating financial fair play by hundreds of millions.

Fellow Russian clubs boosted by state cash

EIC’s Football Leaks project opened last Friday with explosive allegations that UEFA concluded other secret agreements with Manchester City, PSG and Monaco, all of which were engaged in multi-million euro financial doping schemes.

Just before the Zenit settlement, Brian Quinn resigned as chief investigator at UEFA in protest at the association’s questionable behaviour. He was replaced by an Italian associate professor of economics, Umberto Lago. Under Lago, the CFCB's emerging legacy of offering olive branches to certain clubs, while pushing to ban smaller ones, continued.

If financial fair play was designed to level the playing field, it failed. The millions unfairly pumped into some clubs specifically protect them from the possibility of an exclusion on the ground of unpaid bills. “What UEFA did with the big clubs is immoral,” Botosani owner Valeriu Iftime told EIC network. “The smaller clubs have no voice, they have no chance. The business part of football has an interest for the big clubs to live in peace. We are somewhere at the edge of this world. I agreed for my club to be punished.”

He said that he understood that “from a branding point of view… that the big clubs must be supported,” but added that “maybe we can also grow together with them." Botosani was the only Romanian club not given an automatic ban by the adjudicatory chamber, despite the CFCB chief investigator advising otherwise.

But if the organisation felt any embarrassment at the emergence of a two-tier system, it did not show. Within two months of concluding the Zenit settlement, two more financial doping cases at Russian clubs emerged: Lokomotiv Moscow and Dynamo Moscow. When the Russian premiership 2013/2014 season ended, on 17 May 2014, Lokomotiv Moscow sat in third place, one place below Zenit. The Moscow teams had earned two of Russia’s three spots in the UEFA Europa League.

That July, the clubs submitted their break-even accounts to UEFA. The documents, contained in the Football Leaks collection, show Lokomotiv boasting of €30 million combined profits for 2012 and 2013. Dynamo, however, had a deficit of nearly the same size: combined losses of €37 million. Bad for Dynamo, but within the acceptable deviation.

Like Zenit the year before, each club sported remarkably lucrative sponsorship deals: Lokomotiv raked in over €200 million in those two years and Dynamo was not too far behind with €180 million. But, as with the case into Zenit, the charade would soon fall apart under scrutiny. Behind the scenes, there were fraudulent deals with state owners.

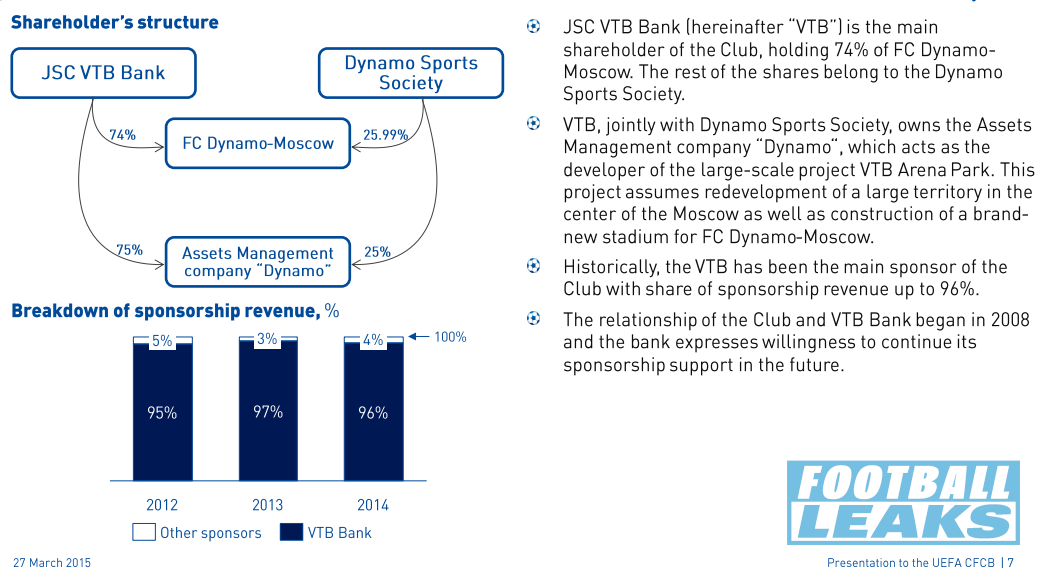

Russian Railways, owned directly by the Government of Russia, holds 90 percent of Lokomotiv’s shares, and is one of the largest companies in the country because of its near-monopoly on rail transport services. Last year, it had revenues of €20 billion. Most of the remaining 10 percent share is held by state-owned VTB Bank. VTB was also the majority owner of Dynamo Moscow until December, 2016.

The UEFA investigation documents show that Lokomotiv willingly disclosed that Russian Railways was responsible for 94 percent – or €187 million - of its €200.5 million sponsorship revenue. And it means that the transport firm also pays 86 percent of the club’s entire two-year budget of €220 million. UEFA learned that VTB bankrolled Dynamo’s sponsorship, too, with the bank paying 96 percent sponsorship, constituting around 85 percent of the club’s €211 million budget.

In October 2014, CFCB chair, Rodrigues, wrote to both clubs asking for a breakdown of their sponsorship deals, and, crucially, a ‘fair value assessment’ to determine if the contracts were fair. Unlike the cases of PSG and Man City, however, Rodrigues allowed both teams to choose their own audit firm.

Lokomotiv opted for PwC, and Dynamo, Repucom.

The resulting audit reports, seen by The Black Sea, were unambiguous. Financial doping was rife. Russian Railways contracts with Lokomotiv were, according to PwC, inflated by more than 100 percent, meaning deals costing €187 million were really only worth a maximum of €87 million, still a generous figure. Repucom declared in its report that VTB overpaid by a massive 1000 percent - its €90 million deals worth only €9 million.

The two Russian clubs were in trouble as the revaluation wiped a whopping €155.7 million from Dynamo’s income, creating a deficit of €192 million, and around €100 million from Lokomotiv. What was once a healthy profit for the club known as the Railroaders was now a €59 million budget hole.

On 9 February, UEFA finally opened investigations into financial breaches at both clubs. It also set a date for a Nyon meeting on 27 March 2014, just over six weeks away. In the meantime, the clubs sent, in early March, an updated set of fiscal records, covering 2014.

It made grim reading for Dynamo; its deficit grew to over €302 million. Lokomotiv, however, rejoiced at a new, miraculous windfall in its financial sponsorship that was curiously similar in size to its Russian Railways deal.

A showdown in Switzerland

Lokomotiv and Dynamo met UEFA officials in Nyon on the same Friday in March. Like in the Zenit hearing 18 months earlier, the purpose for the clubs was to argue its case in front of the financial control body administration and hope to avoid the adjudicatory chamber and its heavy sanctions.

Dynamo’s presentation document reveals an honesty about its reliance on VTB cash. The bank provides 96 percent of the club’s sponsorship, Dynamo said, and without it the club would crumble. It then presented a financial forecast, stating that in order to survive, Dynamo needed VTB to pump at least €90 million per year into the club’s purse. This meant €540 million for deals worth barely €40 million.

The new chief investigator, Umberto Lago, pressed the association’s adjudicatory chamber to punish Dynamo with a ban from all UEFA competitions for having a, albeit somewhat imaginary, deficit close to €300 million. The adjudicatory chamber did just that and the club was banned for one year.

During the process, however, UEFA did Dynamo a favour by acceding to the club’s request to have full details of the VTB bogus contracts redacted from its published judgement, depriving Dynamo’s Russian and European rivals from knowing the full extent of the club’s half-a-billion-euro scam.

VTB, which sold the club to the Dynamo Sports Society for one ruble at the end of 2016, told EIC that it "is currently not a shareholder of FC Dynamo, its representatives are not part of the leaders of FC Dynamo. For the moment, there is a partnership agreement between VTB and Dynamo Moscow. We believe that this contract corresponds to the market value and is at fair value, in accordance with the UEFA regulations."

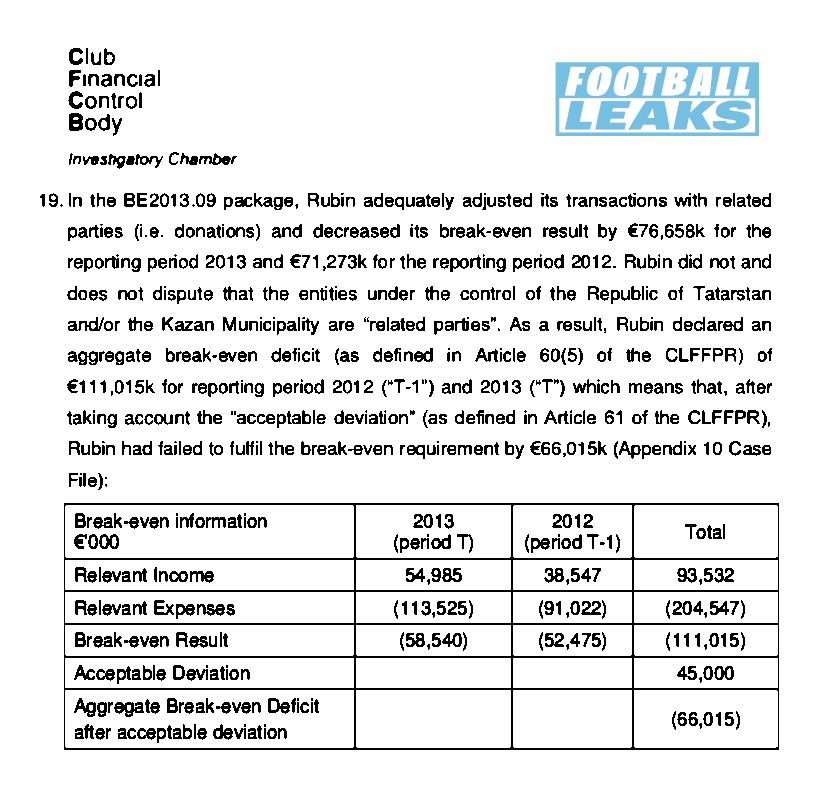

As the next highest place club, Rubin Kazan took Dynamo’s spot in the 2015/2016 Europa League. But it was at the time subject to a fair play settlement it had signed the year before, when the CFCB determined that the club’s state owners – the municipality of Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan, a semi-autonomous federal state in Russia – had provided €60 million in dodgy loans and donations that hid huge losses.

Rubin Kazan did not answer The Black Sea's questions, but it seems that the club somewhow failed to satisfy the break-even terms in its UEFA agreement as it was banned by the body earlier this year.

At the Nyon meeting, Lokomotiv’s officials told UEFA a similar story to Zenit’s. Russian football was a growing market, but still in early development; revenues were hampered by poor distribution of TV broadcasting money and a digital infrastructure; and, of course, Russians have a “lower level of disposable income per capita” versus other Europeans.

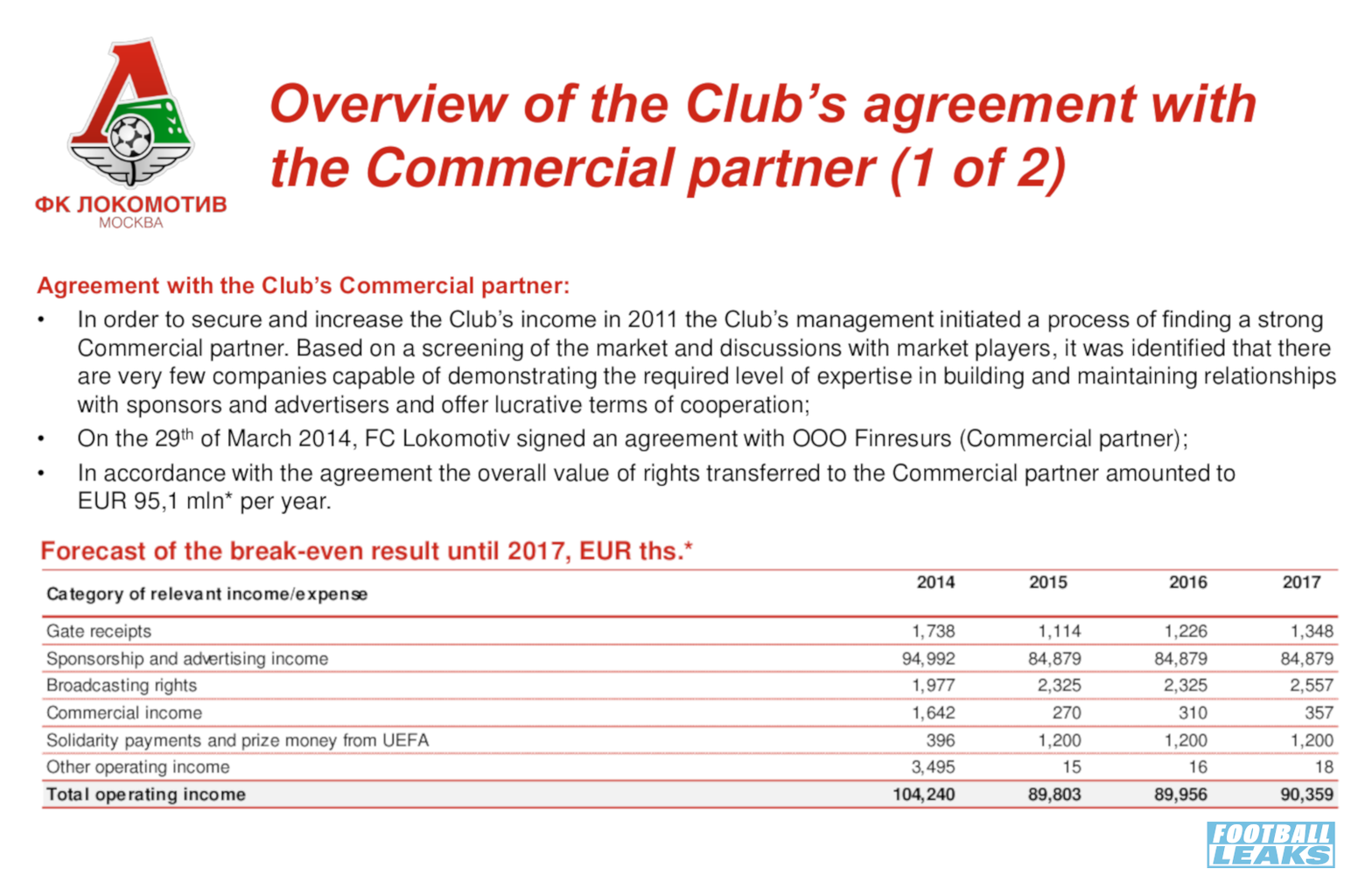

Despite all of these problems, however, Lokomotiv boasted of “positive financial results in 2014,” according to the presentation, with a “significant increase” in the club’s sponsorship income, the result of a new, fruitful commercial partnership agreement with a Russian firm. Finresurs.

In only a few months on the job – from March 2014 until the end of the year - Finresurs had managed to generate an incredible €95 million for the club; an increase from €41.5 million in 2013.

This new partner would quickly reduce the club’s annual losses and bring them in line with UEFA rules within a year or two. Finresurs had “guaranteed” the club at least €85 million in annual sponsorship money for five years: €521 million over the life of the contract.

There was one problem. The claims were fictional. The €95 million Finresurs raised in 2014 was entirely from Russian Railways. And so, too, were the rest of the promised future funds. The firm had been hired to act as little more than an “intermediary” to funnel Russian Railways cash –a role it likely received due to the position of its parent company, Trinfico, which manages Russian Railways’s private pension fund, Blagosostoyanie. (This seemingly was never disclosed to UEFA)

When the 27 March meetings were over, the two clubs faced different futures. While Umberto Lago began pushing Dynamo towards the adjudicatory chamber and an outright ban from UEFA competitions, he was preparing a settlement agreement for Lokomotiv that would help bury its financial fraud.

This settlement was signed on 4 May 2015. Lokomotiv was punished with a €1.5 million fine, as well as some restrictions on player transfers. It would also be monitored for the next three years, and promised to make a profit by the end of 2016, roughly 18 months away.

The document omits any word on Lokomotiv’s efforts to hide Russian Railways cash through Finresurs, and its financial doping. Instead, Lago specifically cites Finresurs agreement as justification for the settlement, claiming, falsely, that the club had concluded new sponsorship deals and “presented a financial and business plan” to become break-even compliant within a couple of years.

But Football Leaks evidence reveals that Lago and the CFCB knew Lokomotiv’s figures were the result of fraudulent and inflated deals.

In 2017, a year before the World Cup, both Lokomotiv and Zenit were relieved of the restrictive measures imposed by their UEFA settlement agreements. This year, Zenit ranked the twenty-third richest European club according to ‘Deloitte Football Money League’ - a ranking of football's wealthiest clubs. It is boasting €180 million in revenues.

None of the clubs responded to EIC's questions.

Opening picture: President Vladimir Putin and Gianni Infantino at the meeting of the 68th Congress of the International Football Federation (FIFA) in Moscow on 13 June 2018 (Press Service of the President of the Russian Federation)