Russian president Vladimir Putin opened the 2014 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games at Sochi's Fisht Stadium on the coastline of the Black Sea last February.

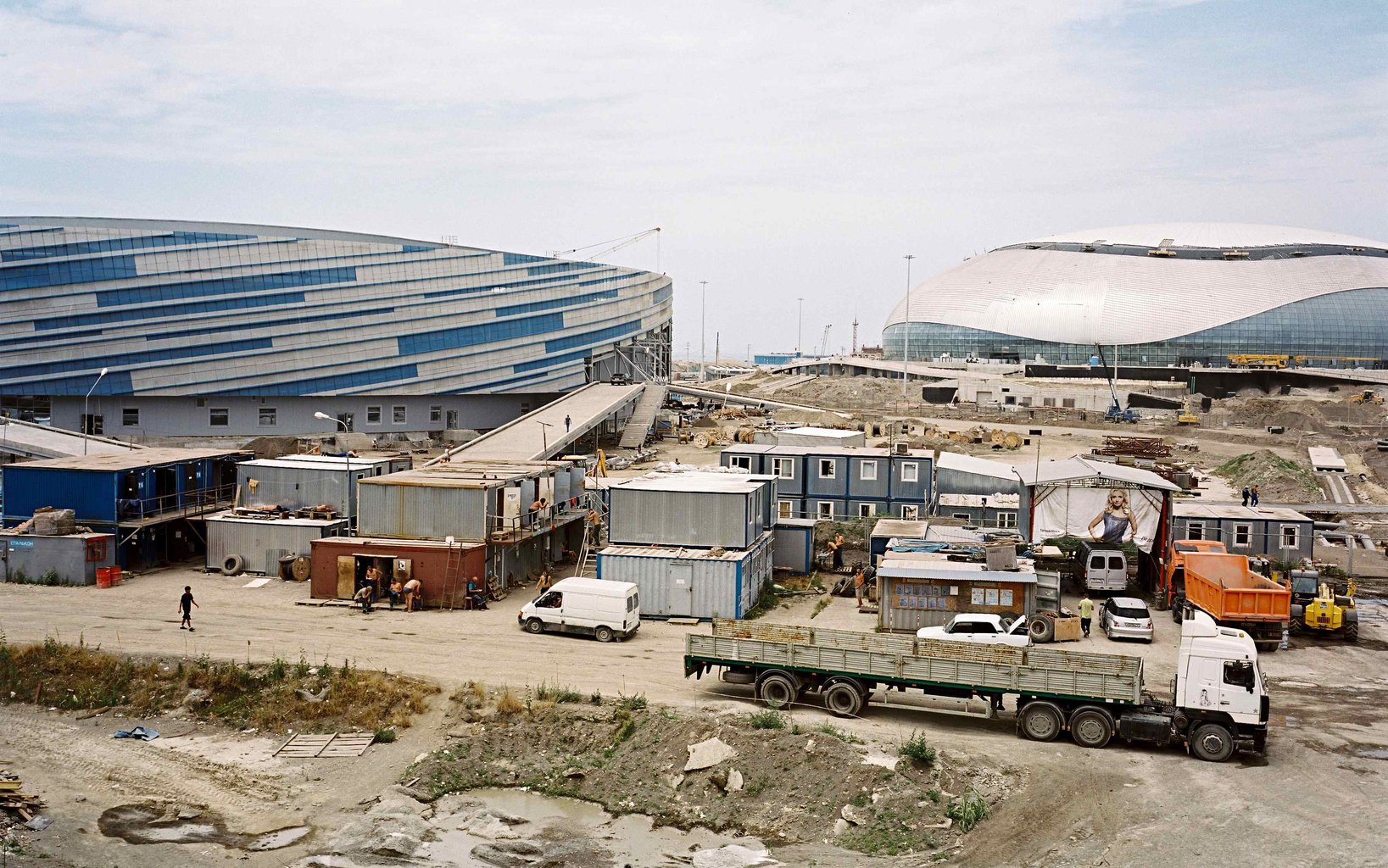

Seven years under construction at a reputed cost of over 40 billion Euro, the Winter Games in Russia are the most expensive sporting event in history. But for the family of Moldovan, Mihai Cernisov, the sight of the lavish and celebrated complex and two-week festivities only causes them pain.

Back in July 2013, newlywed 22-year-old Mihai was eager to make some fast cash; his wife, Mariana, was six months’ pregnant with their first child - a boy - and they wanted to buy their own house. In Moldova, a poor ex-Soviet Republic wedged between Romania and Ukraine, with high unemployment among the young, well-paid work was difficult to find.

A friend told Mihai about jobs on Olympic construction sites in Russia paying 1,000 Euro per month, over five times the average salary in his country. The work was illegal. But for many of the thousands of Moldovans then working in Sochi, this technicality hardly mattered.

Within two days, Mihai and his younger cousin, Iura, were travelling the 1,200 km by bus to the Olympic city, leaving his wife behind and knowing he might not be present for the birth of their son. Before he went, he chose a name for the boy - Bogdan.

"We were told to be careful - that was our training”

In Sochi, a contractor set the two young men to work at the Fisht Stadium, replacing power and video wires. "We were just laying the cables on the fences," Iura now tells theblacksea. "We weren't working with electricity." The contractors promised Mihai and Iura that the proper employment papers were on the way. However, until they arrived, the pair waited at the checkpoint of the site for security guards to wander away, before they sneaked inside. "We didn’t have permits, so we couldn’t always go to work,” Iura says. “We took all the necessary steps. We were waiting to get them."

The pair wore gloves, but received no proper safety training, nor was there a qualified safety officer around. "We were told to be careful," says Iura. “That was our training.” On Wednesday 11 September, the men were working on the cables as usual, stretching them across long metal fences on the perimeter. Iura finished early and was cleaning up the site before lunch. "Then I heard shouting," he says. "I could see the barbed wire above my head twitching. At first, I didn't realise what happened."

Despite assurances from site bosses that the electricity was off, there was a live cable left by another worker hanging low on the fence. No one saw it. But somehow Mihai's touched the cable with his head and was electrocuted, his body thrown several metres backwards. As Mihai's turned blue, co-workers tried to revive him, but their efforts were futile. He had died instantly.

With an ambulance and the police on the way and a dead body lying in the dirt, local security guards forced Iura and his co-workers away from the site. "They knew we didn’t have permits, so they didn’t want any problems," he says. The following day the police called him in for an interview. "They asked a lot of questions," he says. " 'What happened? How did we get there?' They kept asking about the work permits, but I didn’t say much." The police released Iura without taking any formal statements.

Later that day Mihai's older sister Ana arrived in Sochi to identify the body. "I saw the shape of his face, his hair..." she tells The Black Sea. "He looked as though he was asleep." The police released his remains two days after his death, promising to investigate the incident. Ana left the morgue with Mihai's body and several official documents, including a Russian death certificate, signed by two doctors from the coroner's office in the administrative HQ in Krasnodar city. Over one year later, the Russian authorities still have not provided the family with an official report.

The papers, obtained by theblacksea, includes two key inaccuracies: That Mihai died on the construction site of the Formula One racetrack, also under construction in Sochi. And that he was "unemployed". "He was designated as unemployed," Ana says, "but how is anyone supposed to believe that he just happened to be working there?"

"He gave his condolences - then handed me cash"

The employers paid for Mihai's body to be flown home. At Sochi International Airport, a Russian man approached Ana. He never identified himself, but passed her an envelope containing 300,000 rubles (around 6,000 Euro) for "funeral expenses", and promised more. "He just said 'hello' and gave his condolences," she says, "then handed me some cash."

The man was from RZDstroy, a subsidiary of Russian Railways, wholly owned by the Russian state and run by Vladimir Yakunin, a long-time Putin ally. Earlier this year the US government included Yakunin on the the list of individuals sanctioned over Russia's annexation of Crimea.

In 2010, Russian Railways became an official partner of Olympstroi, the Russian state corporation tasked with overseeing much of the contracting and construction for the Games. Russian Railways was allocated around 23 per cent of the Olympic budget - eight billion Euro. But its tenure is marred by scandal and allegations of overpricing.

In March this year, Russian business paper, Vedomosti, reported that the company faced a 240 million Euro fine over RZDstroy's failure to fulfil a contract for apartments in Sochi. Russian Railways and RZDstroy deny any involvement with Mihai's death, telling theblacksea that the company suffered only one fatality during construction in Sochi; on 20 December 2013, a man - who they refer to as a welder named "S V Bukhonov" - died after the cradle of a crane fell on him.

The company ignored further questions about about the deaths of Mihai and Bukhonov.

At Mihai's funeral, one of his bosses told Mariana that RZDstroy would provide ongoing financial help to her and Bogdan. She received one further payment of 600 Euro. Then the money stopped.

Numbers of dead “do not add up”

A 2013 Human Rights Watch report estimates that 70,000 migrant workers were involved in constructing the Sochi Games. The workers suffered long hours, unpaid wages, over-crowded accommodation. Some saw their passports confiscated by employers. The true number of the working dead at the site is not known. But there is a disparity between the official figures and those of the workers’ country of residence.

Earlier this year, theblacksea contacted Moldovan authorities requesting death certificates issued from Sochi. The Ministry of Internal Affairs collects data from families applying for state funds for burial costs. These records show that 33 Moldovans died in Sochi since 2009 and 19 between 2012 and 2013. The Russian Labour Inspectorate, responsible for counting the dead, told reporters that 26 workers died in Sochi in 2012-2013.

Most migrant workers came from Central Asia, with a minority from Moldova, So the likelihood that over three-quarters of the deaths were Moldovan alone is slim. In a statement to reporters, the labour inspectorate claimed that "the safety of workers was ensured" in Sochi and that worker fatalities at the games site were "four times less than the average" for Russia's construction industry as a whole. By contrast, the UK suffered no worker fatalities during the construction of the 2012 Olympic Games. Vancouver had one death in the run up to the 2010 Winter Olympics. China claims ten workers died while constructing the Beijing games in 2010.

But former Olympic workers tell theblacksea that deaths were an everyday occurrence, and that numbers of dead reachto the hundreds;.the brunt of these were from the Uzbek community.

Slave class

Landlocked authoritarian republic Uzbekistan now provides so many work migrants to Russia that, in the Russian language, the term "Uzbek" often describes anyone from ex-Soviet nations of Central Asia. The Russian Federal Migration Service stated, on 4 December, that Russia has 2.15 million Uzbeks officially registered there. The real number once the illegal migrants are counted is significantly higher.

Many leave to escape appalling human rights abuses and forced labour in the cotton fields. Once in Russia they often find poor living conditions, xenophobia and illegal work in the country's 150 billion USD per year construction sector. When the time came for construction in Sochi to begin, Russia exploited this new Uzbek class as useful human capital. The plight of this illegal labour force echoes that of the Nepalese migrants in Qatar, where hundreds have died building for the 2022 World Cup.

Mahsud Abdujabbarov has just spent two months in a prison cell in Tashkent, the Uzbek capital. In August, Russian authorities expelled him from the country. When he arrived in Uzbekistan later that day, the secret police snatched him at the airport .

His crime? As Head of the Inter-Regional Center for Education of Migrants in Moscow he fought for the legal rights of migrant workers. He had recently published details of ongoing research into the deaths of Uzbeks in Russia. His work, conducted with two Russian colleagues, claims that 48,500 Uzbeks died in Russia in the past four years. These numbers come from the Ministry of Emergency Situations of Russia, the Ministry of Interior, local hospitals and airports shipping coffins to Uzbekistan.

Some of the deaths, he says, are from natural causes, such as heart failure, but also include accidents and racist murders. Forty-two percent of the dead, nearly 18,000, died on Russian construction sites. Abdujabbarov tells theblacksea that at least 120 Uzbeks were killed during the construction of Olympic facilities, according to his research.

"There is a mixture of reasons for workers’ deaths," he says, "but the main culprits are employers. Dangerous work was conducted by people without professional education and without proper control. "Another problem was that people had to work without any rest..." he adds, "sometimes without even sleeping... Some workers died due to lack of concentration because they were exhausted."

Since his release from prison last month, Abdujabbarov has fled Uzbekistan and is in hiding, unable to return to Russia or to his wife.

Olympic construction firm: "millions" paid in bribes

Migrants' rights also struggled under the climate of corruption infecting the games. With a 50-billion-dollar price-tag, the global sporting event suffered widespread accusations of graft in how the state organised the construction contracts. Employees at the Russian state firm overseeing the games, Olympstroi, were investigated for embezzlement in 2012, but so far there are no formal charges.

In 2010, Russian officials also opened a probe into Vladimir Leschevsky, former government official in the Department of President’s Affairs supervising construction contracts, for accepting bribes. Valery Morozov, former head of Russian construction company Moskonversprom, now living exile in Britain, tells theblacksea that he personally paid millions in black money to Leschevsky.

The official, he says, would then pressure him to subcontract work to a group of ex-Yugoslavian companies. One of these companies was Putevi Uzice, based in Serbia, owned by businessman Vasilije Micic. Putevi received hundreds of millions of Euros in contracts to build or reconstruct sites in Sochi, including the city's airport, and the Hotel Kamelia, a luxury 5-star resort. Despite the huge money flows, several employees and NGOs accused Putevi of failing to pay wages.

One Moldovan worker, Misha, worked illegally in Sochi for Putevi from 2012 to 2014. He tells theblacksea that he knew of at least seven workers who died working for Putevi alone. "Three of them were from Uzbekistan," he says, "and Putevi paid to cover them up." Putevi did not respond to journalists' questions.

Charges against Leschevsky were eventually dropped, and the government discreetly moved him to a different department. Morozov claims that the video evidence against Leschevsky is "lost". It was, he alleges, more likely used by the Russian secret service (FSB) to bribe the official.

Talk of dead Uzbeks was rife in Sochi, according to workers there. Misha and another source told theblacksea of a rumored shallow grave containing half a dozen bodies in Rosa Khutor, where the Olympic skiing events took place.

“Some families got 1,500 Euro, others got nothing”

On the opening day of Games, then-Turkish prime minister (now President) Recep Tayyip Erdogan met with Vladimir Putin. Putin openly praised the efforts of Turkish construction companies, stating, "I want to express our gratitude to Turkish contractors for their work in Sochi... What we see here is our common achievement.” But we reveal here how Turkish companies suffer from strong allegations against their working practices.

One Uzbek worker, Adijilon, tells us how he witnessed the deaths of three workers illegally employed by Turkish construction firm, Ant Yapi, while building the Hotel Azimut. "One guy was run down by a big crane," he says. "The driver didn't see him... and couldn't understand us shouting because he was Turkish. They had to call the police... [because] the Uzbeks wanted to kill him. [Ant Yapi] bosses sent the driver back to Turkey."

In another incident, in September 2012, Adijilon says the Ant Yapi site bosses demanded that an Uzbek man climb up six floors to pour concrete into the building. "At first, [the man] refused," Adijilon said, "he told them it wasn't his job and that he was afraid of heights." But bosses insisted and threatened to fire him. He fell six floors to his death. He had a wife and four daughters back home. His friend took his body to his family in Uzbekistan.

"Some workers said Ant Yapi gave the family 100,000 Rubles (around 1,500 Euro today). Others say they got nothing," says Adijilon. Ant Yapi did not respond to our request for comment.

“Those who will die, will die. What is important is the job.”

Turkish architect Destan Kiliç arrived in Sochi in at the beginning of 2013, employed first by Russian construction firm TransKomStroy and then Turkish company, Monolith. These Turkish companies worked closely with Istanbul-based Sembol building leisure facilities in Krasnodar Polyana, a 800,000 sqm site in the hills overlooking the city. Kiliç left Sochi in February this year, after arguments with bosses over the treatment of migrant workers.

Kiliç says that the project relied on high numbers of illegals and deaths were in the hundreds during her time there. "There were a lot of Uzbeks among the dead and unregistered workers,” she says. “I would always hear: 'this worker died today on this site'... 'somebody fell again'... 'Something collapsed on a worker.'" Nothing was ever recorded, because they were unregistered.

She told of one incident where a worker, without proper equipment, scaled a tall height and fell to his death. When the construction company found his body, their staff attached a safety belt to the corpse and then took pictures. They did this, she says, so that they could blame the worker for his own demise.

"Health and safety measures were non-existent," she says. "There were no safety personnel, as required. In Sochi, companies would just register an engineer as the safety person." Kiliç complained to her bosses, but the disregard for worker welfare was coming straight from the top. During one dispute, her Sembol Construction

boss, Aytekin Gultekin, made it clear that safety was not a priority. "I was told by management: 'This is war. Everything is permitted.'" alleges Kiliç, "'Those who will die, will die. And those who will be deported will be deported. What is important is completing the job.'"

Kiliç also says this brutality extended to Uzbek women in Sochi, hired as cleaners, servers and kitchen staff. She says sexual assault by management was widespread. "The men forced the women to sleep with them," she added. "The whole atmosphere was disgusting.”

A manager at Sembol, who asked to remain anonymous, confirmed to The Black Sea that the rape and sexual assault of Uzbek women was frequent and conducted with impunity. "It was extremely, extremely common..." he says. "Most cases do not go to court because Uzbek women are uneducated villagers working illegally. Management always turns a blind eye."

World Cup: a defeat for workers’ rights

On 2 December 2010, the FIFA Executive Committee voted, in Zurich, for Russia to host the World Cup 2018. The tournament is set to take place across 11 cities, mostly in the west of the country. It is another huge construction project, which Russian prime minister Dmitry Medvedev claims will cost around 20 billion Euro. As with the Winter Olympics in Sochi, much of the hard lifting will fall onto the backs of migrants.

In the city of Samara, just north of the border with Kazakhstan, the ministry for Labour, Employment and Migration puts the number of migrant workers already at 56,000. Spread across the 11 cities, the total is likely to be in the hundreds of thousands. But the Russian parliament has taken steps to ensure that the real figure might never be known. In July 2013, the government passed a law removing various provisions of the Labor Code afforded to World Cup 2018 workers, including migrants.

Applicable to all FIFA and Russian companies, contractors, sub-contractors associated with the tournament’s building projects, it suspends worker rights on overtime pay, working hours and holiday. Additionally, it allows companies to hire - and fire - migrant workers without obtaining any permits from the state or informing the tax or migration authorities.

The law is of significant concern to international labor organisations who say that it facilitates unaccountable migration and hiring practices - even for forced or child labor. According to Anna Bolsheva, Policy and Campaign Officer for Building and Woodworkers' International, a Geneva-based member of the Global Union Federation, "officially" five World Cup workers have already died.

"Unfortunately, it is difficult for migrant workers to get legal status in Russia," she tells theblacksea. "When they come to Russia they find themselves in a very vulnerable position.... And employers take advantage. In the Sochi Games, this advantage reached it maximum: rights of workers were brutally violated and it was not possible to find people who were responsible for these violations, including cases of death."

Search for justice: cancelled

In Moldova, Ana explains how Mihai's family have lost hope of seeing Russian Railways in court over her brother's death. Legal experts advised against it, telling the family it would be too expensive and there is too much corruption in Russia to hope for a favourable outcome.

Two months after Mihai's death, his wife Mariana gave birth to their child, which she named Bogdan, as he wanted. "I don’t want anyone to go to prison over this," Ana says. "But Mihai was all the support that Mariana had. He wanted to go to Sochi for three months until Bogdan was born. He wanted a place of his own and he was a really hard worker."

While at the morgue in Sochi, Ana met the families of three other Moldovan workers who had died on construction sites. They told Ana they were envious. She was confused, until they explained that it was because she could fly her brother’s body home; they had to drive the corpses of their men 1,200 km around the Black Sea to give them the burial at home.

This story was produced with support from Journalismfund.eu

(Additional reporting by Stefan Cândea, Zeynep Sentek)