In the last days of 2010, Beşiktaş president Yıldırım Demirören appeared on a Turkish sports channel to announce that the club was about to bag Portuguese international striker, Hugo Almeida. What was different about this transfer, he said, was that Beşiktaş had not paid a cent of the player’s €2 million transfer fee. Instead, Beşiktaş had “used a fund to purchase Almeida,” and proudly declared that Beşiktaş was “such a star club that this fund came to us with the offer.”

Days later, in the beginning of January, Almeida arrived in Istanbul by way of Demirören’s private jet and signed a contract loaded with a hefty salary and extraordinary benefits that included sports cars, planes and a luxury apartment.

But Demirören’s golden deal ended up turning into a financial nightmare for Beşiktaş. Documents obtained by the German news magazine Der Spiegel and shared with The Black Sea, and its partners in the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network, show that the contract Beşiktaş signed with the third-party investment fund contained such strict clauses that the club was forced to repay the entire transfer with heavy interest three years later.

The files also reveal that one of the investors in the fund was Ali Koç, head of Turkey’s richest family and the vice-president at the time of rival Istanbul club, Fenerbahçe.

Also connected to the fund is Almeida’s intermediary, the Portuguese superagent Jorge Mendes, who in the same period brokered several deals with Beşiktaş and Demirören that netted Mendes millions in improper and illegitimate fees, as revealed by The Black Sea, last Friday.

Mendes fund retains minority share in player's rights

Almeida signed for Beşiktaş during the “Portuguese wave”, when Demiroren transferred seven Mendes players and one coach to Beşiktaş in a one-year period between the summers of 2010 and 2011.

Beşiktaş was generous with the contracts for these Portuguese, but especially so with Almeida, shelling out a €2.5 million salary, as well as a host of luxurious extras, like a brand-new Porsche, private jet leases, €11,000 a month for an apartment, business-class flights, and a second car of his choosing. Mendes was paid handsomely too, receiving a €1.5 million fee.

The club might have felt there was money to spare; they had not contributed to any of the €2 million transfer fee paid to German club Werder Bremen. Instead, Demirören did a deal where Beşiktaş would buy Almeida outright for €2 million, but then a third party investment fund called Quality Football Ireland Limited would purchase 45 percent of Almeida’s ‘economic rights’ from Beşiktaş for the same amount. This practice, known as Third Party Ownership, or TPO, meant the QFIL was entitled to 45 percent of any future transfer fee - if Beşiktaş sold the player.

When the deal was concluded, Demirören proudly boasted that, “[with this fund] we opened a very important door for Beşiktaş and Turkish football. Bringing a player for free is like selling him for profit.”

In mid-2010, not long before the Almeida deal was concluded, former Man United and Chelsea chief executive Peter Kenyon and the football agent Jorge Mendes set up Quality Sports Investment (QSI). This company's investor presentation shows that QSI was half owned by Jorge Mendes’s Gestifute with the other half owned by CAA Sports International, a leading sports agency. Mendes and Kenyon were also advisors to the QSI.

QSI is a key part of an offshore investment structure that collects money from groups of investors and gives it to QSI. QSI then loans the money back to Quality Football Ireland Limited and other vehicle companies to purchase players’ economic rights. This way, each LP owns varying degree of several players.

Kenyon and QSI were intimately involved in drafting and approving the Economic Rights Participation Agreement (ERPA), signed with Beşiktaş on 23 December 2010, that granted it 45 percent of Almeida’s economic rights.

The shared ownership was confirmed by Demirören during his TV appearance, where he claimed that Beşiktaş owned “all of the player, [but] if the player is sold, 55 percent of the transfer fee is going to our club.”

But Demirören’s left out a lot of key information. Football Leaks documents detail how the Beşiktaş president failed to disclose that he had signed a proxy ERPA agreement worth ten percent of Almeida’s future transfer fee with Mendes’s Irish firm, Gestifute.

“Gestifute are getting 1.5mn EUR for the player signing for Beşiktaş and 10% sell on fee,” writes Karish Andrews, a sports lawyer working for Mendes. “This is a sell on fee rather than pure economic rights but we now understand why Beşiktaş marked up our contract as such. As long as Beşiktaş pay the 10% from their share I can’t imagine PK [Peter Kenyon] will have a problem with this and Beşiktaş should represent that they hold 100% of the economic rights - they have just contracted to pay Gestifute a 10% sell on fee.”

The words are different, but the effect is the same. Not only was Mendes paid for agent services through improper intermediary contracts, and his QSI fund deeply involved in Almeida’s economic rights, he also owned ten percent of Almeida, raising serious questions about conflicts of interests, none of which were properly disclosed.

When Beşiktaş made an offer, in 2011, to buy QFIL’s 45 percent interest in Almeida for €6 million – three times what the fund had paid for them – it was also sent to Kenyon and QSI (the deal never materialised).

Demirören, for his part, failed to divulge much of this, as well as what would happen if Beşiktaş did not sell Almeida before his employment contract concluded at the end of May 2014. As this day approached, it was clear the player was not destined to stay at the club, as discussions reveal he was complaining about Beşiktaş’s failure to pay his wages on time, and was keen to move to another club – another football agent told one European club, according to Football Leaks documents.

Beşiktaş would soon come to understand that there is no such thing as free player.

The multi-million payback

While Demirören had comforted fans on TV with claims that “the [QFIL] fund cannot do anything with the player without asking us.” The agreement between them suggests the opposite. Under a specific clause, Beşiktaş has a responsibility to prevent the player from becoming free agent, otherwise “the Club shall pay to the [Fund] an amount of to the Grant Fee plus interest at the rate of 10% per annum.”

This deal was one of many that the new Beşiktaş administration had to tackle after Demirören departed the club in early 2012. The clause meant that Beşiktaş was slapped with a €2.75 million bill from QFIL for a player who, in the summer 2014, was already out of the door.

Two lawyers who reviewed the Almeida contract agreed that it is aggressive. Sports law professor at Loughborough University in the UK, Serhat Yilmaz, told The Black Sea that the agreement “clearly highlights the extend of power a third-party may have over the transfer policy of the club”.

Shervine Nafissi, a lawyer and PhD candidate in sports law at the University of Lausanne, where he specialises in economic rights agreements, said that the fund pushing the club to transfer the player before his contract ends “clearly contravenes the principle of contractual stability provided by FIFA and even by state laws.” He added that the contract in its entirety is very favourable for QFIL: “[The fund] is never going to lose.”

Professor Yilmaz agreed with this point: “There is no risk for [QFIL] under this agreement.”

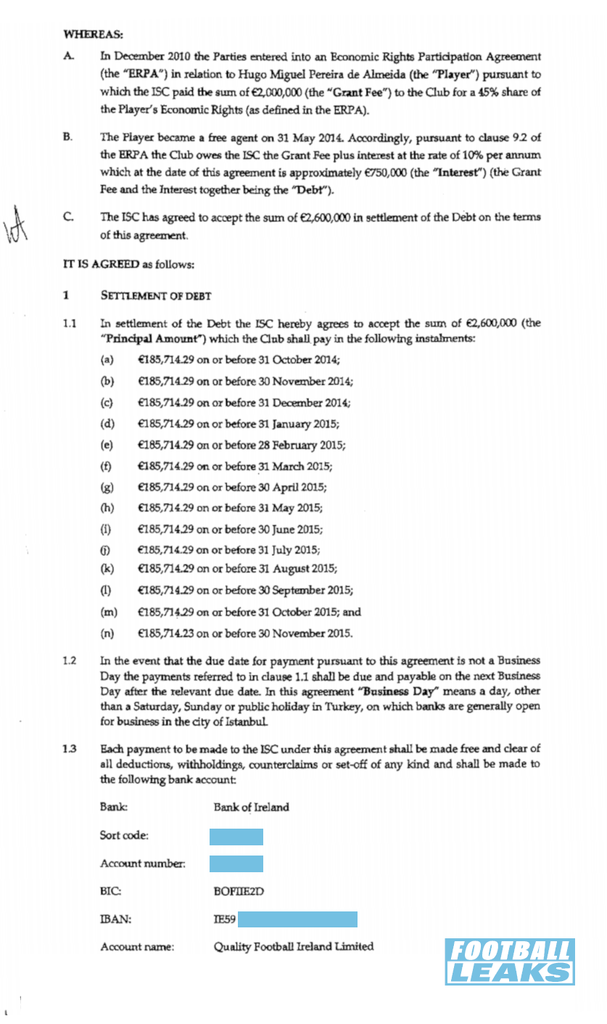

The cash-strapped Beşiktaş eventually negotiated a settlement agreement with QFIL on 15 October 2014 that reduced this amount to €2.6 million, which the club was to pay in 14 installments.

Another clause in the agreement demands that Beşiktaş pay QFIL €4.5 million if it refuses a transfer offer that the fund has accepted. This grants provides QFIL with a significant pressure-point and inordinate decision-making powers over the club. Nafissi said that clauses like these “place the club in a considerable degree of dependence on the third party.”

He added: “Once the offer is on the table, the club has a gun to its head: either it accepts but loses its player. Either he refuses, but he must take several million out of his pocket to compensate the third party.“

Yilmaz agreed that the clause is “crazy”, suggesting that the fund practically says to the club “Either listen to me or you will pay more.”

The ERPAs and the role of Third Party Ownership in the transfer market became a difficult subject for FIFA after it emerged that many well-known players in English Premier League were owned by funds based in tax havens and with obscured ownership structures. TPO arrangements also hid serious conflicts of interests, such as those with Mendes, who was involved with the Almeida deal via a number nontransparent avenues.

TPO was banned by FIFA in 2015. But a year later, its legacy continued for Beşiktaş, as QFIL hired lawyers to pursue nearly €900,000 in outstanding fees from the club, stemming from the Almeida agreement. Once again, Kenyon was included in much of the discussions about recovering the money.

Secret investor: Koç of Fenerbahçe

There was another conflict of interest. The cash used to purchase the rights in Almeida came from one of the investor funds, Quality Sports II Investment (QS-II), a limited partnership based in Jersey, which in return held the player’s economic rights. Documents from the Football Leaks data-set shows that QS-II was offering ten percent annual return to anyone who invested a minimum of €250,000.

Copies of the full list of QS-II investors reveal that among them was an “Yildirim Ali Koc". Ali Koç is the head of the wealthiest family in Turkey and vice president of the family’s conglomerate Koç Holding. At the time he was an investor in the fund, he was also a board member and vice-president of Fenerbahce, a rival Istanbul club. Today, he is the club’s president, having been elected in June this year.

The fund provided regular updates to its investors detailing the players who were on the fund’s books, meaning Koç should have known that he had a financial connection to Beşiktaş and therefore a possible conflict of interest. Beşiktaş did not answer questions about whether it was aware of this fact

Koç did not reply to The Black Sea’s questions.

Opening image: Hugo Almedia of Besiktas celebrates after his goal against Maccabi Tel-Aviv during their Europa League Group E soccer match at Inonu stadium in Istanbul, on September 15, 2011. (MUSTAFA OZER/AFP/Getty Images/Guliver)