Turkey's new mega mosques attacked as kitsch parody of Ottoman greats

Michael Bird, Zeynep Şentek

Spot the difference

Below is the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, northwest Turkey, built by Ottoman-era architect Mimar Sinan in 1575.

A masterpiece of mosque design, this is a symbol of the peak of Ottoman imperial glory.

Its main elements are a centralized dome, set about by smaller semi-domes, octagonal pillars and four tall minarets.

Photo credit: Filanca, Wikimedia Commons

Now Turkey is undergoing a massive expansion of mosques around the world.

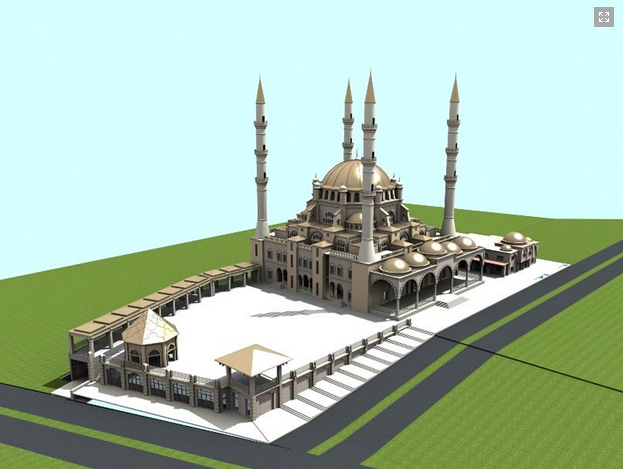

Below is the new design for a mosque in Nicosia, Cyprus.

A centralized dome, set about by smaller semi-domes, octagonal pillars and four tall minarets.

Below is another in Corum, central Turkey, which opened this year.

A centralized dome, set about by smaller semi-domes, octagonal pillars and four tall minarets.

Below another in Kirikkale, also in central Turkey, which opened this year.

A centralized dome, set about by smaller semi-domes, octagonal pillars and four tall minarets.

Below is a design for Tirana, Albania, due for 2017.

A centralized dome, set about by smaller semi-domes, octagonal pillars and four tall minarets.

And finally this in Camlica, Istanbul, due to open next year.

A centralized dome, set about by smaller semi-domes, but this time boasting six tall minarets.

Parody of genius: architect's view

“What we see here is an exact copy of a design from the Ottoman times,” says Oguz Oztuzcu, architect and former president of Istanbul Independent Architects’ Association.

“Even the chief Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan never copied another design - even during his own epoch."

These projects risk becoming cut-price representations of past architectural glories.

“It’s appropriate," adds Oztuzcu, "to call them kitsch.”

But the Turkish leadership is proud of plundering its Ottoman heritage for creative ideas.

Minister of Environment and Urbanization, Erdogan Bayraktar, said in 2013 that then Prime Minister (now President) Recep Tayyip Erdogan “grew up with Ottoman culture, he wants to see the reflection of the culture he grew up with. He loves it.”

No consultation, no demand: planner's view

But there is resistance to Istanbul’s Camlica Mosque, despite its extensive building works. The Camlica Hill has been a protected public space since 1960s and a court case is currently raging against its construction, following a complaint by the Istanbul Chamber of Urban Planners.

To resolve the dispute, the court commissioned an expert report, which stated that the mosque is symbolically very important and that the public will benefit from its construction.

However President Erdogan's political party Justice and Development (AKP) did not even pretend to hide that the Camlica mosque was more than a monument to its own legacy.

“The aim of building this mosque in Camlica is to leave a symbol signifying the AKP party era,” Minister of Environment and Urbanization, Erdogan Bayraktar, said in 2013.

“Since the Ottoman times, the normal way of building mosques is that locals come together and decide they need a mosque - they set up an association to collect money and build the mosque for themselves,” says Istanbul Chamber of Urban Planners' board member Tuba Inal Cekic.

“Now you see the state taking on this role of building mega mosques with a budget that isn’t transparent. We don’t know exactly who's funding it."

The construction happened without consultation with the planners or any consensus from the population.

“As urban planners, our problem is about the location of the Camlica project and that there was no demand from local people,” says Tuba Inal Cekic.

“We see mosques as social constructions and, as with all social constructions, you need to see if there is demand for such a project socially. Are there enough people who would be benefitting from such a project? With Camlica, there is no demand.”

However the Government has changed the regulations so now technically they can build a mosque every 200 meters.

“They want to build a mosque wherever they find empty space,” says Tuba Inal Ceki. “We want these spaces to be used as creches, parks or playgrounds. There is so much need for space in the cities."

Instead there are so many mosques that Tuba Inal Ceki says they are even empty on religious holidays.

“We would never oppose building of mosques," she adds, "but there should be standards, there should be a need and a demand. But we face criticism for saying these things and are accused as if we were infidels.”

Click here for the story revealing Turkey's massive global mega-mosque building plan

Follow us