Following tough US lobbying to force the EU to lift its ban on the cultivation of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), Romania’s law-makers are switching their views to favor controversial biotech practices

Romania has about six per cent of the total utilized agricultural area in EU

"By increasing efforts in Romania now [2005], the US will have a strong European ally with common interests and shared beliefs to combat the EU's anti-GMO position in the years ahead," Thomas Delare, US Charge d'affaires, Bucharest (Wikileaks, 2005)

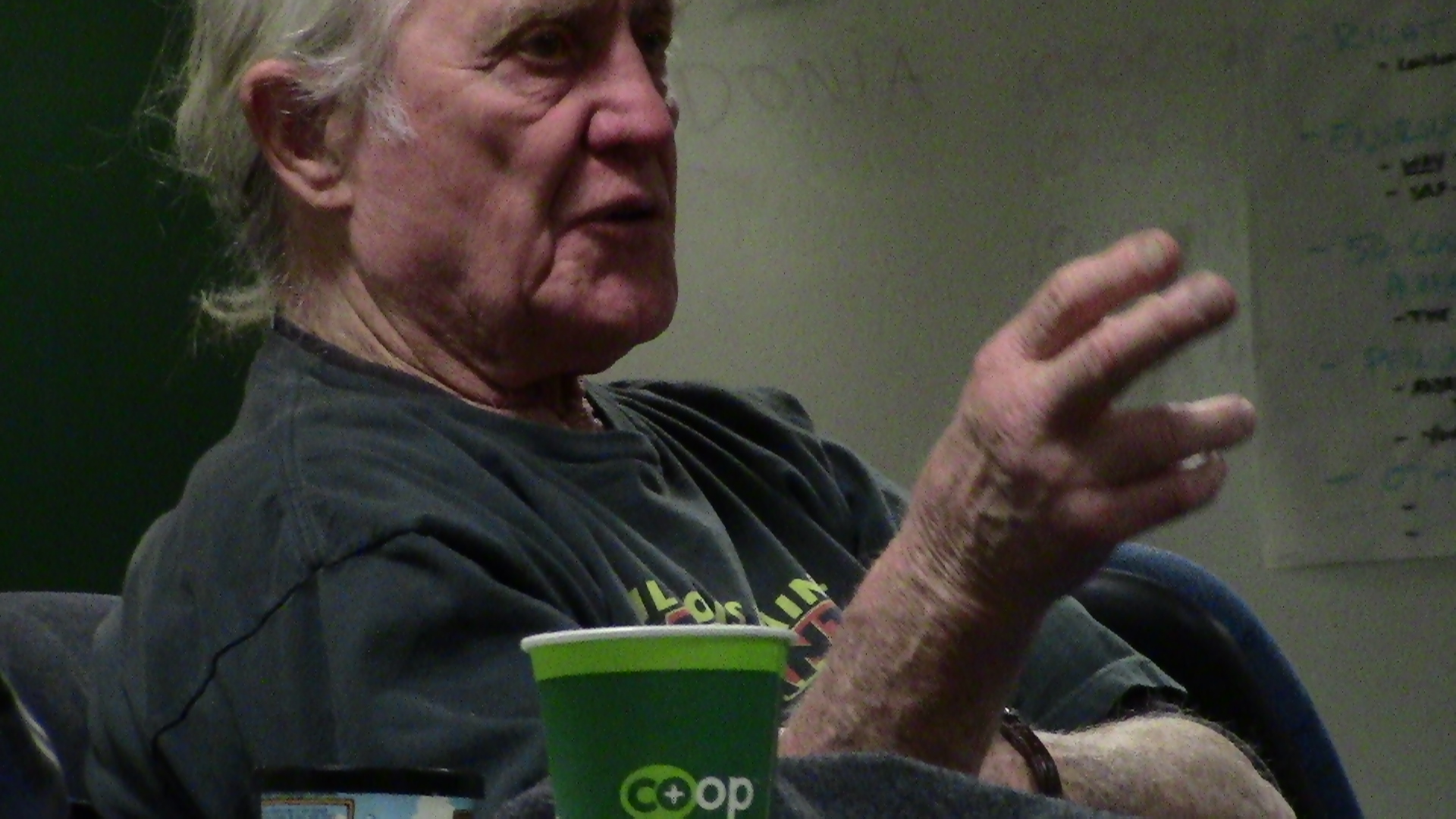

“In 2011, the US Supreme Court allowed practically unlimited corporate donations and ‘dark money’, for which we don’t even know the source. If you give this money [to congresspersons] in campaigns, you’ll receive something in return,” Bill Lambrecht, author ‘Dinner at the New Gene Cafe’

This transnational investigation was reported and written by Vlad Odobescu of the Romanian Centre for Investigative Journalism. Vlad was a Reporter-in-Residence at the New England Center for Investigative Reporting between January and March 2013. The Reporter-in-Residence Program was made possible by a generous grant from the Open Society Foundations.

Romania has banned cultivation of almost all genetically modified organisms (GMOs) since 2007, but recently Bucharest’s Parliament hosted a crucial vote revealing its historic opposition to GMO cultivation is changing.

A major agricultural force in the European Union (EU), Romania is viewed by US biotech companies as a strong ally for lobbying in Brussels to lift the EU ban on GMO cultivation.

Over the last seven years, biotech companies and the US State Department have spent vast amounts of cash promoting this controversial form of farming to Romania’s key decision makers.

Now this investment seems to be paying off.

On 15 March 2013, a draft law in the lower Chamber of the Romanian Parliament called for a ban on growing, importing and marketing of products containing GMOs.

This law was proposed by the opposition Social Liberal Union (USL) in 2010 to ensure that products containing GMOs had to reveal this provenance on their packaging.

The law took three years to come to the floor. Since then the USL has gained power in Romania.

Now this Governing bloc rejected its own proposal in a vote where 218 opposed the bill, with 72 in favor.

The lead-up to this ballot was monitored by the US State Department. Four days before the vote, the Foreign Agricultural Service of the US Embassy in Bucharest expressed its concern about the proposed ban in a report to the US Department of Agriculture.

"If approved, the new draft law would clearly place at risk biotech seed producers," it stated.

Almost every time Romanian leaders prepare to vote on a ruling regarding GMOs, the US Embassy in Bucharest and American politicians use the pressure of soft politics on local politicians to favor the biotech industry.

The Americans have wooed key actors in Romanian agriculture through financing programs that allowed Romanian politicians to travel to the US to study American agriculture. They also arranged for American biotech experts to meet with Romanian officials in Bucharest.

The most important player in this industry, US mega-corporation Monsanto, also wields influence in an effort to convince Romanian politicians to introduce large scale agricultural biotechnology in their home country and the EU.

The company has contributed to the political campaigns of dozens of American Congresspersons and Senators. Some of these politicians traveled to Romania to try to demonstrate to local officials the benefits of biotechnology.

"This illustrates the connection between Monsanto and the Romanian authorities - this is how the mechanism works," argues Ramona Duminicioiu, president of The Info Center about Genetically Modified Organisms in Cluj-Napoca, which opposes GMO cultivation in Romania.

The stakes are high. Monsanto has invested around 150 million USD in its Romanian seed production units and is planning to spend another 40 million USD on its facility in Sinesti, Ialomita county, over the next two years.

GMO cash bets on Romania

Since 2005, Bucharest has been visited by over nine key Congresspersons and Senators who received funds from big farming.

Between 2004 and 2012, these elected officials cashed in a total of 0.57 million USD in campaign donations from Monsanto and Political Action Committees (PAC) supporting the use of GMOs.

In 2008, when the Romanian authorities were considering banning the only GMO allowed to grow on the nation’s soil, Monsanto’s maize MON180, US Senator Richard Lugar came to Bucharest to meet then-Prime Minister Calin Popescu Tariceanu and then-Minister of Environment, Attila Korodi.

The press release following the meeting says nothing about agriculture, but a State Department cable released by Wikileaks is more revealing:

“Highlighting his experience as a farmer, visiting Senator Richard Lugar on 28 August encouraged Minister of Environment Attila Korodi to permit the use of more advanced agricultural methods in Romania, including biotechnology,” the cable says.

Lugar, at that time a member of the US Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry, had received 15,000 USD in campaign donations from Monsanto between 2000 and 2012, according to Opensecrets.org, a group that tracks the influence of money on US politics.

Starting from 2004 until 2012, he also received a total of 26,500 USD from CropLife America, Cargill, Inc. and Archers Daniels Midland, organizations and companies promoting GMOs.

Lugar was also a firm supporter of the Global Harvest Initiative, a group promoting the interests of the biotech industry. Its membership includes biotech giants such as Monsanto and Pioneer.

Former Minister Korodi says that the meeting with Senator Lugar was “surprising”.

“It seemed curious that there were so many diplomats - the US Ambassador with a whole team,” he says now. “They were very well prepared for this meeting. They were expecting from me a more flexible position [on permitting GMO cultivation], but I wasn’t flexible.”

We tried to contact Lugar through his press office, but we did not get a response.

Big money equals big demands

Monsanto is a huge contributor to American political campaigns. According to opensecrets.org, in 2012 Monsanto’s PAC, Monsanto Co., contributed a total of 385,000 USD to the campaigns of 88 Congressmen and Senators.

PACs interested in promoting GMOs contributed a total of 4.37 million USD in the same electoral cycle, according to MapLight.org, a research organization revealing money’s influence on politics.

There is nothing immoral about such contributions, argues Michael Phillips, a biotech adviser to governments, industry and NGOs.

“That goes on in all political campaigns in the United States,” he says. “Companies usually donate to both the Republican Party and the Democrat Party. It’s no different than the auto, manufacturing or telecommunication industries.”

Agricultural companies spend large amounts of money lobbying for or against legislation and regulation in Washington. Among these, Monsanto invested the largest amount on lobbying federal institutions and agencies on behalf of agricultural services and products in 2012 - a total of 5.97 million USD, according to opensecrets.org.

Monsanto representatives in Romania say that the company participates in the US political process in a manner similar to many businesses, labor unions, trade groups or issue organizations, in part through a political action committee.

But Bill Lambrecht, journalist and author of a book challenging genetic engineering, ‘Dinner at the New Gene Cafe’, argues that the system favors immoral links between politicians and corporations.

“Two years ago, the Supreme Court allowed practically unlimited corporate donations and what we call ‘dark money’, for which we don’t even know the source,” he says. “If you give this money [to congresspersons] in campaigns, you’ll receive something in return.”

During the same period, American authorities were using public money to help the biotech industry develop in Romania, which could bring benefits to Monsanto.

The US State Department finances scientific conferences attended by high-ranking local politicians. According to cables distributed through Wikileaks, these events were financed from Biotech Outreach funds, which aim to promote the acceptance of GMOs in some countries.

The funds were administered by the Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs within the US State Department.

In late 2008, then Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice informed US embassies in 22 “key countries”, including Romania, that they could use this cash to invite specialists to speak about the benefits of biotechnology to local politicians and scientists.

Why does the US target Romania?

Romania’s history of GM cultivation in the 1990s and early 2000s means the country remains a soft touch for US corporations and the US State Department in its search for a GM-friendly lobbyist in Brussels.

Following the break up of the Communist bloc, Monsanto built on its presence in Romania to expand its sale of hybrids and GMO seeds.

Just before the ex-communist country joined the European Union in 2007, Romania had become one of the largest growers of GMO soybeans in Europe. In 2006, the number of hectares seeded with GMO soybeans was around 137,300, almost double compared to the year before and three-quarters of the nation’s total soybean crop.

Based on its experience using biotechnology, Romania represents a functional model that could convince the EU authorities to change their attitude to GMOs.

In 2005, Thomas Delare, then charge d'affaires at the US Embassy in Bucharest, wrote in a cable to the Department of State, according to Wikileaks: "By increasing efforts in Romania now, the US will have a strong European ally with common interests and shared beliefs to combat the EU's anti-GMO position in the years ahead."

In Washington, Romania's biotech past is also considered a success.

"Romania has, in some ways, more similarities to the United States than some other parts of Europe,” says one US State Department official. “It’s more accepting of new technologies and it’s unique because it has real experience with the success of biotechnology. And it’s something that few other European countries have. I think there’s an opportunity for Romania to be a leader within Europe, to explain that there are indeed benefits to farmers [from GMOs]."

Therefore the use of Romania as a ‘fifth column’ of pro-GM lobbyists within an anti-GM EU seems to have been the strategic plan of the US in the last decade.

GMOs: why the EU hate and the US love?

The US is a strong promoter of GMO solutions for agriculture, while the EU is against this form of “mutant” crop invading its rolling hills and plains.

Part of the reason for this opposition is economic. The major producers of GMOs are American and if the EU opens its farmland to develop GMOs, this will be to the benefit of seed companies from outside its borders.

But another reason is the psychology of the two economic blocs. The EU takes a more cautionary approach to an untested form of agriculture which betrays its traditions, while the US prefers a pragmatic stance which is centered on next year’s balance sheet.

“In the US, we adopt a risk-benefit analysis that is mainly economic,” says Will Allen, a pro-organic farmer from Vermont, opposed to GM seeds. “We say - ‘Well, if it kills one person in a million, then it is tolerable, because the economic benefits are greater than the loss of a life’. Europeans take a precaution because they're not sure whether it is dangerous.”

The large percentage of American farmers who embrace biotechnology seems to be a strong argument for the US State Department’s position.

"It’s pretty clear that farmers love the technology,” says one State Department official. “The adoption rate in US, Brazil and China has shown that pretty much every time you have access to the technology, you end up with [up to] a 90 per cent adoption rate.”

Currently EU legislation prohibits the growth of GMOs in its 27 member countries, with two exceptions approved by the Union's control institution, European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) - one type of corn and one type of potato.

But EU member states rely on massive GMO soybean imports for animal feed because they do not have the capacity to produce competitive non-GM crops. According to the European Commission, the member states imported 11.9 million tons of soybean and 21.2 million tons of soymeal in 2011 and 2012, the bulk of which is from GM sources. This has led the pro-GM lobby to accuse the EU of hypocrisy.

In July 2010, the European Commission proposed a new set of rules that would give Member States full responsibility for cultivation in their territories. For Monsanto, such a decision would be highly lucrative. The decision is pending, as member states have different views on biotechnology.

“After South America was conquered, Europe is one of the last ‘resistance movements’ Monsanto has to defeat,” says Brian Tokar, from the Institute for Social Ecology, a pro-environment organization based in Vermont.

Permanent Revolution: a century of Romanian Agriculture

Romania should be an agricultural powerhouse. With a perfect mix of forest and pastoral lands in the north and centre and flat warm plains in the south, the country belongs to a rich and fertile belt of black earth running from Bulgaria through Moldova to Ukraine.

Agricultural land stretches over 13.3 million hectares, more than half of the country’s surface. Romania has about six per cent of the total utilized agricultural area in EU and the seventh largest farmland in the union, after France, Spain, Germany, UK, Poland and Italy.

Between the two world wars, during the leadership of Romanian King Ferdinand I, a land reform bill divided the large estates into lands for nearly 1.4 million farmers, and exports of wheat and corn increased.

After the second world war, the new communist state confiscated the land in a 15-year nationalization process. The state gave Romanian peasants shares from the crops they gathered as employees of collective farms.

As the Communist dictators Gheorghe Gheorghiu Dej and Nicolae Ceausescu introduced a programme of rapid industrialization with new factories that were hungry for workers, the Romanian population transformed from rural to urban.

In the 1960s, peasants represented around two thirds of all Romanians, but three decades later the urban population became predominant.

The communist authorities adopted a mechanization process and introduced large scale use of pesticides, which increased yields at the expense of ruining farming traditions.

US agri-giant Monsanto started developing its business in Romania in 1975, where the company opened an agency for selling herbicides.

In 1989, months before the change of regime, the Communist Party adopted a draft that contained a perspective over the next two decades of Romanian agriculture until 2010.

Biotechnology played an important role in the plans of Ceausescu.

The document called for a “new agricultural revolution” which included prioritizing research on creating varieties of plants and hybrids “with superior genetic resistance to low temperature, drought and disease”.

In 1990, the state gave land back to the peasants, creating millions of small agricultural holdings. Two million of these holdings are under one hectare (two acres). But many of these plots are stricken with inefficient farming methods, while others lie dormant, leading many analysts to believe that Romania is a country ripe for huge agriculture exploitation.

The country’s most important crops are wheat, corn, sunflower, oilseed rape and soybeans. After 2007, when Romania became an EU member, most exports focused on the European market.

In 2011, the country exported agricultural products with a total value of 57 billion USD, of which 41 billion USD were bought by EU countries.

Bill Frothingham and Sarah Capungan also contributed to this report.

This investigation is a version of longer report published by The New England Center for Investigative Reporting (NECIR).