While grand residential projects help regenerate the outer centre of the Spanish capital’s district of Delicias, Romanian beggars build shanty-huts in the dirt

.jpg)

Delicias. In English this means ‘Delights’. A district in outer central Madrid. A warm Wednesday. Huge new apartment complexes of brick and concrete tower either side of a railway. Connecting the two estates is a wide footbridge, with a smooth incline to allow the passage of bicycles. Below the shining new buildings are fenced-off tennis courts, where buff players sport fancy designer wear, and serve aces across the clay.

But alongside the railway is a plot strewn with rubble, overgrown bushes and two massive rusting water towers, separated from the new blocks by a white wall. Under the footbridge are shacks of wooden boards nailed together and covered with tarpaulin. A mini favela takes shelter in the shadow of this huge development. On a sofa outside a shanty-hut sits a man in his late fifties, listening to the radio and drinking beer from a glass teacup. Next to him is a stroller filled with aluminium foil.

This is Costică, from Băilești, a small town in Romania’s arable heartland close to the Danube. He won’t talk to journalists. So we pretend we’re researchers for a university. He will not let us take his picture.

Before the 1989 revolution, Costică worked as a store manager and his family lived well, because he had access to food and goods. “Back then I used to work with a pen in my hand,” he says.

When communism fell, the local economy collapsed. Farming in his town turned from a collective employing every resident into a mechanised industry that ran on profit. “They don’t need people anymore,” he says.

In the 1990s, the post-Communist Government gave back land seized by the state to millions of families, hoping to create a new peasant class of smallholders. But each citizen received barely more than an acre. Costică was not impressed by this amount.

He takes a stick, leans out from the sofa and maps out a small square in the dust.

“How can you make farming on that?” he says.

So three years ago, Costică moved with his wife, his son and his sister-in-law to Spain. “As I didn’t have a job anymore, I had to come here,” he says. “God brought us here.”

He has a house and relatives in Băilești, including three grandsons. But he can’t bring them here. This is because the local social services would take the kids away, as Costică isn’t allowed to grow up children between four pieces of wood nailed together underneath a bridge.

As to why he choose this to come to this country and city, he says:

“We heard about Spain from the TV - and now we’re in the capital!”

A rat scuttles across a barbed wire fence. There is no one else here except Costică’s sister-in-law. They speak Romani together. Most of the shanty-huts are unoccupied, because the Romanians from Băilești have gone to Seville to pick grapes. But Costică is too old for fruit-picking.

Instead he says he makes a living from selling scrap wire and aluminium, as well as begging. “I sit in the street and I stretch out my hand,” he says.

He earns up to seven Euro per day, but his family - of three people - can earn 300 Euro a week.

The cops only come to check their papers. “We don’t steal - that’s the last thing we would need. The police leave us alone because we don’t commit crimes," he sighs. "God protected us so far.”

But he says other residents in the squat were not so peaceful. “When they drink, all Madrid can hear them,” he says. Costică claims they were Turkish, although he doesn’t seem 100 per cent sure. A woman in the new blocks called the local mayor to complain when they played their music loud or set bonfires alight.

“We have learned to have smaller fires and not to play our music so loud,” says Costică. Now the local residents are used to him - he says.

There are eight Romanian families on the other side of the camp, from Craiova - a large town near Băilești. They live one hundred metres away. But Costică won’t make the short two-minute journey to speak to them.

“Because they are from another race,” he says.

We were here in Spain last September to examine forced labour run by criminal gangs. In 2013, the Spanish police say the only proven cases of work exploitation for begging came from Romania. From those taken to trial, eight victims were minors between the ages of 13 and 15. In 2014, the sale price a family would cash in selling their child to a begging gang in Spain was between 1,000 and 1,500 Euro.

Vans in Madrid drop off beggars at crowded areas within the city centre at seven A.M and pick them up in the evening. These include old and disabled people - many of whom could not come to Spain on their own. The Catholic Charity Esperanza details one case of a woman and teenage child forced into begging.

“They had to work for 12 hours in the same place every day, and to obtain 50 Euro every day. If they failed - they were not given food, or were beaten up,” says Marta González, general coordinator at Esperanza.

.jpg)

But among the Romanian beggars of Delicias, the atmosphere is calm, and there are no kids or gang bosses, claim the residents. On the other side of the footbridge, two men are sitting outside a shanty-hut. One is large, almost bald, with blonde-hair, blue eyes and thick black tattoos, the other is smaller, pockmarked, his eyes damp and red. He is smoking red Pall Malls and holding out his thumb, which is bloody, and wrapped in a bandage.

When we arrive, a girl in her twenties hides behind a curtain to a hut, guarded by a plastic white pony.

These men are Florin and Florin. Both are from Craiova. They don’t want to talk to journalists. But they let us pull up a chair and speak to them - because we 'are Romanian'.

The big Florin says he cannot work in Romania - and he shows us a scar that has cut into his ankle.

They arrived here three years ago. How do they make their money?

“Here we find a piece of metal or we beg,” says Florin.

They says they can earn 400 to 500 Euro in a month from their activities. But even if they manage six to ten Euro every day, “it’s pretty good”.

Sometimes they send home 100 Euro a month.

Both Florins say they don’t steal. “The cops would kill us if they caught us,” says big Florin.

There is no running water, nor is there electricity, but the larger Florin days he does not need it. “We arrive at ten at night and we go directly to bed,” he says.

On this wide abandoned railway siding squat people from around the world. There are Spanish, Romanians, and Turks (although no one here is quite sure they are Turks). But each group keep to their own separate shanty community, and the Romanians here don’t even know how to speak Spanish. Big Florin say they have no problems with the neighbours.

“We are on our field, they are on theirs,” he says.

In the shade of a tree is a black man in his twenties, sitting down, nodding and mumbling to himself. His shirt is open, and there is broad and heavy jewellery in faux-gold around his neck.

“Alaska: 10 degrees,” he says, “Canada: 12 degrees, West Coast America, 20 degrees, East Coast America…”

In Spanish, he is reciting the weather forecast to himself. Florin says he does this a lot. Every day, the guy makes money from begging in the street.

We ask where he is from.

Florin looks over with a mix of disdain and a faint note of sympathy.

“Somewhere in Africa…” he says.

This short blog is part of the Eurocrimes project - fieldwork took place in September 2016

We wanted to expose how Romanians are the main nationality of male prostitutes in Rome… and we did not do it

.jpg)

A taxi driver told us where to find boys. His name was Mario. He wasn’t an average taxi driver. He ran an NGO helping women convicts land jobs after they left jail. Also he was an anarchist. And a former soldier who was incarcerated in a military prison after pouring a pan of spaghetti over his senior officer.

Now in his fifties, Mario knew the streets of Rome. He had socialised with murderers and generals. The high and low life of the eternal city. So he was the perfect man to show us exactly where we could see men soliciting boys for sex.

“It’s the opposite of women,” said Mario. “The client hangs out and waits for the boys to arrive.”

We knew from talking to charities, experts in prostitution and east European ex-pats that young Romanian men were the number one nationality of male vice in Rome.

This was not a sleazy part of the Italian capital. If such sleaze even exists. Here were the austere steps of Piazzale Simon Bolivar. At its summit was a brass equestrian statue of the Venezuelan freedom fighter. Nearby were the grand chambers of the Museum of Modern Art.

At the corner of a stone wall, halfway up the steps, and sheltered by an overhanging tree, stood a short 35 year-old man in sunglasses and an upturned collar. Next to him was a bike.

As we moved close to him, he crouched down with a bicycle pump in his hand, ready to inflate his tyres.

We walked into a small grove of cedars and stone pines. Here was a brass bust of Chilean independence leader Bernardo O’Higgins, taking a less prominent position than his Venezuelan counterpart. In the bushes was a blue one-man tent. It was occupied.

Opposite Bernardo O’Higgins was a broken blue chair. Scattered on the ground were empty packets of Durex condoms, Camel cigarette butts and Lube, trampled into the mud, branches and pine needles.

I took a photo with my phone.

It was a bad photo.

It even had my feet in it.

This is where Italian men have sex with Romanian boys - thought to be over the age of 16. The men wait near to the entrance of the grove. Usually older men, as younger men don't need to pay for sex. They stand like lost tourists waiting for a guide, the boys come up to them, they negotiate an amount, and go into the bushes.

But right now there was only one man with a bike. We walked past him on our way out of the grove, and he was still crouching down, with the pump in his hand.

I don’t think he was inflating his tyres.

He looked at us, through his sunglasses.

He seemed to be worried (although we could not be sure - because he had on sunglasses).

Perhaps he was thinking ‘you know that I am not really inflating these tyres. But I am going to keep on pretending that I am, so that you won’t think I am waiting for some Romanian boys.’

But there were no boys.

We needed a new strategy. We went to the outdoor Caffè della Arti, part of the National Museum of Modern Art, and ordered some coffee and water. It was a hot day. Refreshment was essential. But these drinks were expensive.

Then we took turns to walk around the area, seeing if we could find old Italian men or Romanian boys.

I carried a bulky camera and stood behind stone walls trying to take pictures in secret with a long lens. But my lens was not long enough. And there was nothing for me to photograph.

Then I spied a 60 year-old thin man in cap and shades and shorts, slightly sunburnt and looking around at the edge of wall with a small bum bag around his shoulder.

I went back to the cafe, and then my colleague took over the watch.

After ten minutes we realised that it looked as though the only people wandering around looking to procure young Romanian boys were us.

Half an hour later, we saw someone we suspected could be a prostitute. A young man, between 18 and 25, with slightly dark skin, short hair at the sides and a small beard.

We took a picture with a phone.

It was terrible.

He started talking to the old guy.

The conversation seemed to be neutral, but cordial.

Then the younger man walked into the bushes with his telephone, came back, and showed the older guy something on his screen.

What did this picture show?

We were too far away to see.

Then the 'client' left. And the young man in shorts walked in and out of the bushes, seemingly on the hunt for someone else. Did we talk to him? We were staking him out. So we didn’t talk to him. Which was stupid. Did we talk to the old man? No. But we didn’t speak Italian.

We stayed in the cafe for a long time. The waitress kept asking if we wanted anything else. And we did that thing where you order the cheapest item on the menu. Which was a small water.

Then she bought us the bill - which we hadn't ask for.

I think she hated us.

Did we hang around to see if more Romanian boys were arriving. Yes, but we were walking around with big cameras - or trying to take pictures craftily with our phones. Either the people looking for boys saw us, and became scared, or they were not there.

It wasn’t happening.

So we walked back to the grove, which was empty. Someone was coming out of the blue tent.

Who could it be?

It was a tramp with a muddy face and torn clothes.

We looked to the other side of the street. Opposite where Italians have sex with men in bushes.

The building that was standing there.

The Italian branch of the Romanian Academy. Inspired by the Académie Française, this is an institution that aims to “gather the preeminent personalities of Romania’s intellectual life” to build progress in science and art through reflection and action.

I took a picture of the gated classical mansion with its mission statement sculpted in Latin.

And we remained without a story, standing next to a broken chair, on a carpet of cigarette ends, used condoms and muddy jars of empty lube.

Russia and the EU act towards Moldova like two fat men fighting over an after-dinner mint

Chisinau is dark.

In the subterranean walkways, lights are scarce, burnt out, flashing or dim.

People walk in darkness. There are few lamps on the street.

In the playgrounds in the evening, children sway on the swings and climb on plastic castles. They can’t see each other. Parents sitting on nearby benches can’t see them, only hear their laughing and screaming.

By the main square, people wait at the edge of the street for Mercedes minibuses to take them home.

But you can’t make out the number on the vehicle until it is a meter from your face - too late to hail it down.

Whenever you see the shape of a minibus emerging from the shadows, you reach out your arm. They all stop for you. Even if they don’t want to. Even if they don’t take you where you want to go.

When you board a bus, inside it is packed with bodies. All the seats are occupied and there are as many people standing as it is possible for the bus to hold.

They are crushed against the windows. Their heads bent under the ceiling. If you stand, you cannot see where you are supposed to get out. You can only guess at the road - and when you arch your face, wipe the steam from the glass and finally manage to see outside, it is too dark on the street to be sure of the location.

“Where are we?” you ask the people in the bus, “and where are we going?”

I don’t know why there is so much dark.

Maybe the city believes there are not enough people willing to go out at night to merit lighting up the city. Maybe there is no money for electricity.

But it discourages meetings in the late hours. It inhibits communication. It makes people afraid of footsteps behind them. Builds suspicion where there is no threat. It creates borders where none should exist.

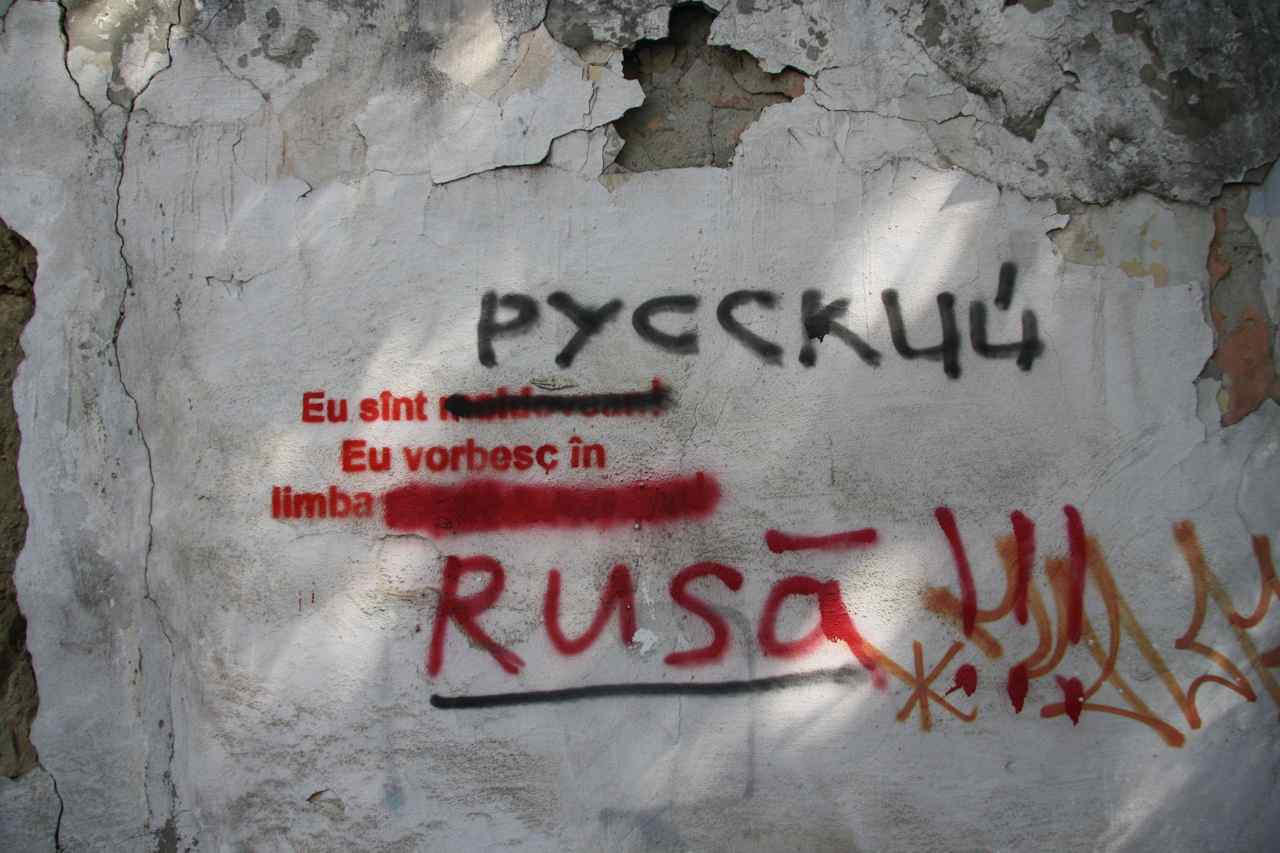

Chisinau is a city where you hear Russian in one bar, Romanian in the next, both on the street and you can speak in both languages - even mix them up - and people understand.

In the towns to the west, they speak more Romanian and to the north, more Russian. Communism's policy of 'the Soviet churn' of moving races from one part of the Union to another created a rich but confused identity at its western border.

Now it has ambitious people with a vision too narrow for the country. Those I stayed with in Chisinau (who spoke Russian, Romanian and French) spend their evenings learning English and German by Skype. There is a desire to transcend Moldova, whatever that may be.

Almost half the workforce is abroad, on construction sites in Moscow, cleaning hotels in Milan, in nursing homes in Lyon, leaving a state of pensioners and kindergartens.

This is a nation in transit. Unsure of what it is, but aware of what it is not. It’s not Romania. It’s not Ukraine. It’s not Russia. Moldova has not yet fully become Moldova.

Torn, yes, but peaceful for now. Although there is pressure from larger states nearby.

Romanian politicians talk up the idea of a union with Moldova.

Prime Minister Victor Ponta, in his bid to be President this year, has a ‘five-year plan’ for Moldova to be part of Romania within the EU.

Meanwhile President Traian Basescu and centre-right candidates for head of state Monica Macovei and Klaus Iohannis also casually employ unionist rhetoric.

But what does Moldova say about that? Only ten per cent want a union with their western neighbour.

This willingness to redraw the map of Europe raises the hopes of people who wish for Moldova to be part of Romania. But it is not realistic.

Some politicians in Romania who I have spoken to, who publicly endorse a union, say privately “I don’t mean it”.

They use this language because the ideal of a greater Romania wins votes from locals and Moldovans with Romanian passports.

Plus it has the added benefit of pissing off Russia - a game Romania has enjoyed ever since its entry into NATO.

But when Romania toys, Moldova trembles.

Russia does the same. It wants Moldova to join its customs’ union - an open market rival to the EU. Posters in Chisinau from the Socialist Party, ahead of the elections next month, advertise the benefits of the union with Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus.

At the same time, Russia enforces an embargo on the sale of Moldovan wine in Russia. Moscow is sending hundreds of ex-pat migrants back to their home country. In a nation of four million people, where 100,000s work in Russia, this wounds the economy and job prospects of the people.

Russia offers one hand out to greet Moldova and, with the other, it punches Moldova in the face.

Moldova is being wooed and fooled by both the east and the west. But there is no long-term plan. They don't know what to do with the country.

To them, the Republic is important, but not that important. This is not Ukraine. This is not Poland. Moldova is disposable, but also significant. From a geopolitical point of view, the empires of Russia and the EU act towards Moldova like two fat men fighting over an after-dinner mint.

Meanwhile Moldova’s political class is equally deceptive. The politicians boast of their connection to western Europe, but the businessmen who back the politicians have financial links with Russia.

Their heart turns to Brussels, their wallet to Moscow.

But on the ground, there are bonuses to this.

From the people I spoke to, a major difference is that this year they have gained the right to travel visa-free through the Schengen space of the European Union, which they can add to their access to former states of the USSR, as well as Turkey and the Balkans.

Suddenly the poorest nation in Europe has the people with the greatest freedom of movement.

.jpg)

An evening in September. There are thousands of people out on the streets. In the distance in the town square is a stage flashing with red and white lights.

Chanteuse Sofia Rotaru is singing with Romanian lyrics, but when she ends a song, she shouts ‘Spasiba’ to the crowd.

The Cernauti-born 70s pop star is now in her sixties, but still packs a crowd when she gives a free concert, this time sponsored by Renato Usati, a businessman turned political opportunist, looking to advance in November's Parliamentary election.

Crowds have brought their children to see Sofia.

But the sound is distorted. She needs to shout to be heard. The stage is no more than a blurry figure surrounded by bright colours.

The audience is standing, watching, unmoved, not lip-synching to the songs or clapping their hands. No one is eating or drinking. No one seems to care. They are here because there is something going on and that something is free.

Two three-year old kids are chasing an empty plastic bottle down the street, moving between the legs of the audience, tripping up, falling down, getting up, grabbing the bottle again, throwing it, all the time laughing and shrieking with joy.

The children don't want to see Sofia.

They only want to watch a plastic bottle skipping down a pavement.

The crowd nearby turn away from the stage and watch the kids, with sympathy and envy.

Twice-elected mayor of a Romanian sea resort and ex-prison detainee Nicolae Matei shows off his private zoo

The mayor of the Black Sea town of Navodari, Nicolae Matei, sips a Turkish coffee in a pavilion, a few steps from his large detached villa in the town center.

A short and stocky man of 46, he arches his eyebrows, giving him the suspicious look of a public official who rules over 37,000 people, but is risking prison in a corruption trial.

Suddenly his smile is broad. His arms are open. With a slow move, he turns to his left, beckoning towards something in the distance.

"Llama!" he shouts. “Come to Daddy!”

Nothing stirs inside the enclosure. A llama chews some hay without responding to the twice-elected leader of the local community.

Around the beast’s legs, goats stir and chickens peck. From another cage, I hear baboons, macaques and creatures of an indefinable race.

"It's like in the jungle," says Matei.

A few years ago, the mayor traveled to a South African nature reserve, an event which inspired him to replicate the experience in his home town.

He started to build this zoo in 2009. But at that point he only housed squirrels.

Now, cages packed with tens of different species surround his house, as though a Biblical Ark has crashed onto a Romanian seaside resort.

The mayor intends to build a huge safari park over a few dozens hectares.

“It should have green areas, water and viaducts, as I've seen in other countries,” he says. “All the tourists who come to the seaside would spend a day visiting this park."

The mayor is also a businessman who owns a chicken farm. He imports the animals through his company and many of the carnivores feed on the meat he processes.

As the mayor takes me on a tour of the cages, he carries a large bowl full of fruit and bread. The animals capture his attention. I cannot interrupt him as he feeds them. The macaques prefer blueberries and grapes, while the mayor leaves an orange inside the fence for a baboon.

Matei feeds a three-week old baby deer with two bottles of milk, which the deer finishes off in a couple of minutes. It is a delicate creature, but Matei says she has powerful instincts.

"I used to leave her in the yard,” he says. “You should have seen the dogs running after her. They couldn’t catch her.”

In a cage under a roof hides a kangaroo. Right now he is not hungry.

The piece de resistance of the enclosure are the lions. Both the male and the female are in the mating period, so it is not the best time to bother them.

The male lion walks near the fence, his head dipped, posing a silent threat.

Matei says that he feeds them with only boiled meat, to reduce their aggressive instincts.

But when the male roars, you can hear the anger in his voice echoing between the blocks and along the boulevards of the town.

This is not the only place where one can find lions in Navodari. The industrial resort is packed with bronze and stone statues of the regal feline, emerging between communist blocks or guarding public institutions. I counted at least a dozen in the most visible places.

There is a reason. Matei is born under the sign of Leo. For him, the lion is a symbol of power.

In November 2012, Matei was arrested on corruption charges. He allegedly tried to bribe a police officer, in order to obtain his support in criminal cases under investigation by the cops in the nearby city of Constanta.

A few days after his arrest, around 1,000 residents of Navodari protested in the central square to petition for his release. He spent five months in detention, but his trial continues.

Nothing in this town seems to move without his approval. Every decision that takes place in the town hall is passed unanimously by the council. When Matei was in prison, vice-mayor Florin Chelaru consulted with him twice a week on local policy.

In the documents related to the case, one of the discussions intercepted by Romania’s graft-busting National Anticorruption Department (DNA) reveals how Matei styles himself as ‘The Emperor in Navodari’.

It seems every king needs a jungle.

Our 80-day journey has come to an end. We travelled 13.000 kilometres, crossed 11 countries (including the separatist republics) and written 53 posts. Our blog will be taking a break now.

We’ll be back with materials from Romania and Bulgaria in autumn when Ioana Hodoiu will take my place as I am heading off on a scholarship. We’ll also write some press materials and we’ll correct the mistakes which had seeped into the on-line journal because of my hurry and ignorance.

The comments section was full of flaming opinions regarding the hacking of the Romanian language, triggered by the names of Caucasian towns. It’s funny to see so much surety and passion in those foreign to the region. The correct spelling of a town’s name is highly disputed even by the locals themselves. Only for Sukhumi there are 30 variations in spelling, each similar to a political statement recognizing an interpretation of the town’s history. My objective wasn’t to write a diploma paper on changes in town names, so I decided to transliterate from Russian one of the ways the name is written on the entry plates into town or to use the name on the English map. As regards comments about words ‘which do not exist in Romanian’, I can only say that, fortunately, the Romanian tongue is very dynamic – otherwise, I would have had to express myself via countless combinations of cheese, cabbage, badger and colt.

As I have met many journalists in the region, we will try to write several materials together which will be published either here or on the CRJI site.

We managed to travel through the countries around the Black Sea without our car being stolen, without falling prey to rakets or without being bamboozled – as we had been warned so often during our trip. However, the most important thing is that not once did we pay anything to the road police, the customs officers or the border guards (except in Transnistria where, out of 10 verifications in a day and a half, we gave in to one and paid a 20-dollar ticket for a fabrication).

After returning home, people kept asking me about differences and similarities with Romania. Regarding major differences, at least on the bank of the Black Sea, nowhere else have I found that mixed atmosphere of swindle, disgust, repugnance and arrogance that crawls up on me every time I make the mistake of visiting the Romanian seaside.

Another major difference is that, except for Romania and Bulgaria, every country is basically an open wound, bearing the deep marks of recent armed conflicts. Even Turkey in relation to the issue of the Kurds. Colleagues my age studied in improvised schools, in bunkers and have lost friends and family in such conflicts; their parents and grandparents were arrested, deported or executed. The region is similar to the Balkans’ situation of the ‘90s, but at a much larger scale and with conflicts spanning over the past hundred years, with abuses and events of an unthinkable cruelty. The international community has had absolutely no firm reaction whatsoever, much less an efficient strategy to mend things.

An important similarity would be the general virulent tone against primitive politicians. The simple folks I talked to, no matter their country or religion, expressed their utter disgust against their own politicians and the belief that foreigners see them as barbaric only because of the latter’s politicians and leaders. Moreover, interethnic conflicts that break out on and off are caused, first and foremost, by mystifications and manipulations for political purposes. Dictatorship, ultra-nationalism and religious zealotry have done the most harm.

None of these countries needs a redeeming leader. An excellent infrastructure, no visas and a free media are the only tools necessary for things to improve instantly.